Section 8 vouchers can help low-income renters, but finding housing is difficult

Listen

Section 8 voucher caps limit participants from renting in high-opportunity areas, and that’s a problem.

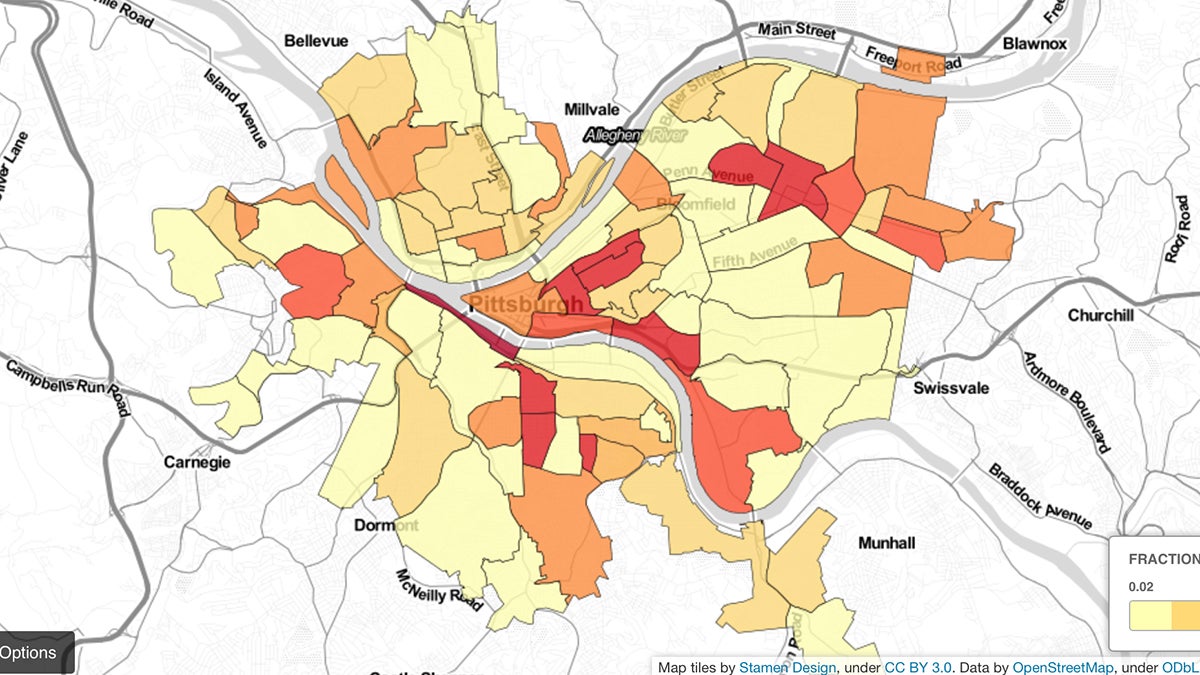

The interactive map above shows the concentration of Section 8 households in Pittsburgh. Explore by clicking on a neighborhood to see demographics, and things like poverty rates, median income and vacant units. ( Map by Irina Zhorov, Data Source: Housing Authority of the City of Pittsburgh and PGHSNAP)

Reuben Sumpter has lived in the East Liberty neighborhood of Pittsburgh for decades. At first he lived in an apartment tower that served low-income people. That high-rise, the East Mall, was demolished. Even in the early 2000s, when the neighborhood’s revival was just starting to show, there were concerns that fewer affordable units would replace the dense high rise.

Sumpter moved to Penn Plaza, another complex in East Liberty that accepted his housing choice voucher. Also known as Section 8, the vouchers help low-income people secure housing by paying a share of their rent in the private market.

Now, the owners of Penn Plaza are redeveloping that property. Sumpter has to be out by the end of February. The most important thing for him as he searches for an apartment is location: he wants to stay in East Liberty. He has Parkinson’s and his doctor is there. The church where he helps out is there, too.

“I know my place, know my way around,” he said. “It’s very important because people that know me they keep the golden rule … we help each other.”

He’s been searching for nearly three months and so far has come up empty-handed.

Sumpter is not alone. In Pittsburgh, just 25 percent of voucher recipients end up using their vouchers successfully.

Success rates, which calculate what percentage of Section 8 participants are actually able to secure housing with their vouchers, vary in Pennsylvania cities. In Scranton, it’s estimated to be around 50 percent. In Bethlehem, 75 percent. In Lancaster, 87 percent. In all of those cities that number has been dropping. (An exception is Philadelphia, where 92 percent of 2015 voucher recipients successfully found housing. According to the Philadelphia Housing Authority spokeswoman, Nichole Tillman, voucher returns were “not due to low housing stock, but rather issues with the tenant’s credit or ability to get utilities.”)

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) last studied Section 8 success rates in 2001. The report showed that at the time the average rate was 69 percent, though it fluctuated greatly from city to city. “Success rates were lower in tight housing markets compared with looser markets,” the report said.

Accepting Section 8 vouchers is voluntary for landlords and people fail to find Section 8-suitable housing for different reasons, many out of the housing authorities’ hands.

Tenants may have trouble passing a landlord’s checks, discrimination against Section 8 tenants still exists, sub-par units fail mandatory inspections, and some landlords avoid the government bureaucracy associated with Section 8.

Something housing authorities do have control over is a voucher’s worth.

How Section 8 works

Congress established the Section 8 program in 1974. At the time, public housing communities were deteriorating physically and some had other problems, like high crime, that made them unsafe. Section 8 sought to give low-income families the choice to find alternative housing. Pittsburgh Councilman Ricky Burgess said choice still matters, because so much depends on the place one grows up.

“If you can only be in certain neighborhoods, then certainly your kids can only be in certain schools … and when neighborhoods don’t have good transportation, then in many ways you’re also being discriminated from good jobs. And if you live in certain neighborhoods and the crime rate is high … It just sort of snowballs,” Burgess said.

But the choice that’s inherent in the Section 8 program is often theoretical because a voucher’s value is limited.

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, or HUD, caps payments through its fair market rents (FMR). Tenants pay 30 percent of their income towards rent, and their voucher covers the rest, as long as it doesn’t exceed the FMR. The rents are supposed to suffice for modest housing – beyond cheap rundown rentals, but not the brand new expensive units, either. HUD establishes FMRs for metro areas, which for Pittsburgh includes seven counties and many communities with varying real estate markets.

David Weber, COO of the Pittsburgh Housing Authority said HUD’s caps lag behind the market, which can be a problem in quickly gentrifying areas. For example, the number, he said, “doesn’t reflect the rental market in the east end of Pittsburgh right now.”

As a result, people hunting for apartments that would be covered by their Section 8 voucher may simply not find them.

“The primary reason is because the market has gone up,” Weber said. “Landlords can get more money without using the voucher program, so they do.”

People who do find housing often end up concentrating in neighborhoods that have more poverty and fewer opportunities, because that’s where the vouchers provide enough for rent.

A map of Pittsburgh’s Section 8 units shows that in some of its more affluent, opportunity-rich neighborhoods, where schools perform better, voucher users are few. In Squirrel Hill South, a pricey neighborhood, there is one Section 8 household. In Shadyside, another prosperous neighborhood close to the city’s main universities, there are two.

Can housing authorities do anything?

Housing authorities have some flexibility in how they administer the federal housing choice program. For example, local agencies can choose to use anywhere from 90 to 110 percent of HUD’s FMR to calculate their vouchers. The Pittsburgh housing authority sets rents at 110 percent of HUD’s figures, to give participants more flexibility.

The agency has received permission from HUD to increase that to 120 percent, something they hope to implement next spring.

Some cities, like Dallas, are trying a different approach. They’ve localized fair market rents. Instead of having a metro-wide rent standard, MFRs are determined by zip code; vouchers cover more in expensive areas, less in poorer neighborhoods. A recent study looking at Dallas’ experience with that approach found that raising rents overall primarily benefited landlords, while localizing them improved neighborhood quality for participants.

So far, just a handful of housing authorities have instituted local FMRs. Dallas’ switch came about because of a lawsuit, but Chattanooga, Tenn., Laredo, Texas, Long Beach, Calif., County of Cook, Ill., and Mamaroneck, N.Y. are part of HUD’s Small Area FMR Demonstration Program. Using this small sample, HUD is testing whether the more localized FMRs get Section 8 participants into higher opportunity areas. HUD has also started publishing small FMRs for metro areas, broken up by zip code. Most housing authorities cannot use these to set voucher values, yet.

Pittsburgh, because of its participation in another federal pilot program that gives the housing authority more autonomy, is an exception. It has the authority to implement local FMRs.

Kevin Quisenberry, a lawyer for the Community Justice Project in Pittsburg, says that would be a better approach than raising the metro-wide rent standard. He points to downtown Pittsburgh, where rents have gone up with redevelopment, as an example of why. “The payment standard even at 120 percent FMR is never going to provide very many rental opportunities in downtown Pittsburgh. Which is, as you know, a very high opportunity area,” he said.

The Pittsburgh housing authority did explore the option of localizing rents but decided against it.

The housing authority points to its efforts to bring more affordable units online. It has used its autonomy to redevelop public housing, and built some units that use project based vouchers – similar to a traditional Section 8 voucher, but attached to a specific unit (which also limits choice). The housing authority also recently announced a $10 million commitment to build an additional 200 affordable units in the city.

Right now, East Liberty in Pittsburgh is about 11 percent Section 8 units. Pittsburgh’s 110 percent FMR standard should cover rent there, according to HUD estimates. But as the neighborhood develops and attracts wealthier newcomers, that may change.

For Reuben Sumpter and other Section 8 participants who want to take advantage of the new East Liberty, that choice may already be out of reach.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.