Scale of immigrants’ political, economic impact depends on who you ask

About 160,000 unauthorized immigrants live in the Philadelphia region. Deducing their impact depends on who you ask.

Protesters angered by President Donald Trump’s executive order that prevented refugees, visa and green card holders from entering the US chant pro-immigration slogans at Philadelphia International Airport in January. (Branden Eastwood for WHYY)

“Life, unauthorized” is a series from WHYY/NewsWorks that looks at the personal immigration stories of individuals who are living in the Philadelphia region without legal status. Immigration is not only a major political issue locally and nationally; immigrants also have an economic impact.

—

Philadelphia lies more than 2,000 miles away from the nation’s busiest border for illegal immigration, but the issue resonates as strongly here as anywhere in the country.

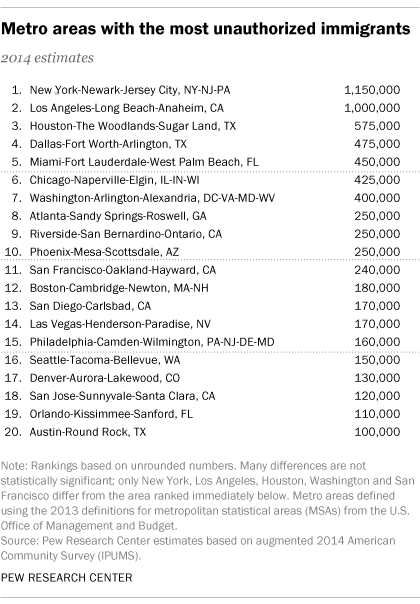

About 50,000 unauthorized immigrants live in Philadelphia, with another 110,000 in the outlying region, from bustling Bensalem, in Bucks County, to tiny Toughkenamon, in Chester County.

Despite the rhetoric around the issues of authorized and unauthorized immigration, so many immigrants call Philadelphia home that they’ve helped reverse urban flight and boosted the economy of the nation’s poorest big city by paying taxes, spending money, buying homes, and starting new businesses.

That’s one of several reasons why city officials declared Philadelphia a sanctuary city, limiting law enforcement cooperating with federal authorities intent on deporting unauthorized immigrants.

“I’m not going to turn my back on people who decided they wanted to live in Philadelphia,” Mayor Jim Kenney said in January and has said repeatedly.

Since President Trump took office, immigration has taken center stage nationally and locally, with the commander-in-chief vowing to crack down on immigrants here illegally and punish cities that shelter them. But the pressure has led many to double down on their commitment to that community.

“Being divisive, racist and xenophobic is not good for our country, it’s not good for trade, it’s not good for education, it’s not good for medical research, it’s not good for the economy, it’s not good for anything,” Kenney said.

Several area colleges, including Swarthmore College and the University of Pennsylvania, also have declared themselves sanctuary campuses, vowing not to share the immigration status of students or to cooperate with federal officials without warrants.

Thousands have rallied and protested in the Philadelphia region for immigrants’ rights since the presidential election. In some cities around the country, smaller rallies by citizens protesting unauthorized immigration occasionally pop up.

Some groups, such as the nonprofit New Sanctuary Movement in Philadelphia, are training people how to resist raids by immigration officials.

And immigration authorities have come.

In Chester County, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents on April 26 arrested 12 mushroom farm workers who were unauthorized. It was the first such raid in that region since the 1990s. Fears of deportation loom large in the county’s rural southernmost reaches, where the mushroom farms that fuel the local economy rely on immigrants for labor. The farms also fear the loss of business.

“There’s uncertainty with the workers, with their communities,” said mushroom grower Chris Alonzo, president of Pietro Industries. “And there’s uncertainty with businesses. They’ve slowed down their investment in new tractors, new equipment, because we’re unsure of the workforce situation.”

At the Berks County immigration center north of Reading — one of just three such centers in the U.S. that detain unauthorized immigrant families — dozens of detainees went on a hunger strike last year to bring attention to their prolonged incarceration. Despite pleas from democratic U.S. Sen. Bob Casey, authorities earlier this month deported two Honduran asylum-seekers — a mother and her 5-year-old son — who had been in custody there for 16 months.

Deportation fears have spiked so much that panicked people imagine ICE checkpoints where there are none, and ICE officials have appealed for calm.

“These reports create mass panic and put communities and law enforcement personnel in unnecessary danger. Any groups falsely reporting such activities are doing a disservice to those they claim to support,” a local ICE agent said in a WHYY report in March.

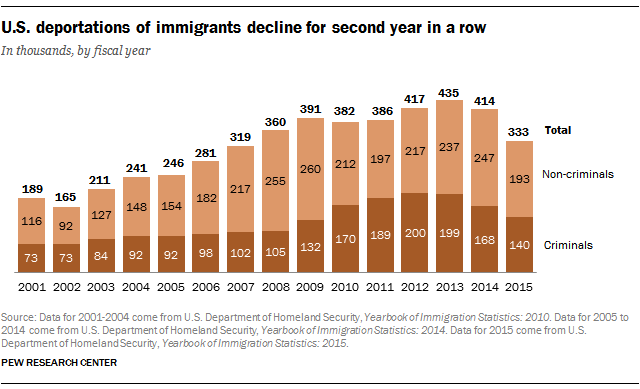

In reality, data shows that deportations are actually down, even though immigration arrests rose 38 percent nationally – about a rate of 400 unauthorized immigrants a day put in custody – in President Trump’s first three months in office, according to ICE data.

The pace of removals under President Trump has lagged behind President Obama, whom critics dubbed “Deporter in Chief.” Deportations in Obama’s last years in office sagged from his earlier tenure, both locally and nationally, data shows. Immigration authorities deported nearly a quarter of a million unauthorized immigrants in fiscal year 2016, down from a high of nearly 410,000 in fiscal year 2012, statistics show. Agents in ICE’s Philadelphia office, which covers Pennsylvania, Delaware and West Virginia, deported nearly 3,300 unauthorized immigrants in fiscal year 2016, down from more than 5,800 in fiscal year 2013, ICE data shows.

Trump has vowed to crack down on immigrants who commit crimes — a guiding principle for Obama as well. Fifty-eight percent of those deported last year nationally (and 78 percent of those from Philly) had a criminal conviction, federal data shows.

But Obama targeted criminals convicted of serious crimes, while reports indicate that many of those deported under Trump had no criminal history.

“We’ve gotten tremendous criminals out of this country,” Trump told Fox News in April. “I’m talking about illegal immigrants that were here that caused tremendous crime. That have murdered people, raped people — horrible things have happened. They’re getting the hell out or they’re going to prison.”

But mayors of sanctuary cities argue that their stance makes their cities safer, because crime witnesses and victims who are in the country without papers are less likely to step forward if they fear being detained and deported.

Studies also show that immigrants generally break the law less often than U.S.-born citizens. Academics theorize that’s because they face harsher penalties — deportation — for criminal behavior, but also because those who emigrate tend to be more motivated and ambitious, and so less likely to break the law.

“The administration projects the image of the criminal alien. That’s disgraceful, because it’s not true, yet it’s the kind of political strategy that works,” said Peter J. Spiro, a law professor who specializes in immigration law at Temple University’s Beasley School of Law.

Instead, Spiro said, immigrants have become a critical part of the U.S. economy.

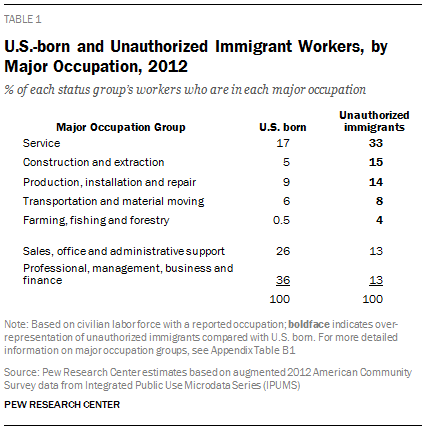

The Pew Research Center found that unauthorized immigrants made up more than 5 percent of the nation’s workforce in 2012, adding up to more than 8 million people working or hunting for work. Most work low-skill jobs, more than U.S.-born workers, representing a bigger share of the total labor force in such jobs as farming (26 percent), cleaning and maintenance (17 percent), and construction (14 percent), Pew found.

Still, like crime, the impact of immigration on the economy is another issue where the answer depends on whom you ask.

The conservative Heritage Foundation blamed unauthorized immigrants for placing a $54.5 billion fiscal burden — in public education, welfare benefits and services like police, fire and highways — on “the rest of society” in a 2013 report.

Yet the nonpartisan Economic Policy Institute found that immigrants play a positive role in the economy for several reasons: They are disproportionately likely to be working, and demographically, most immigrants are prime working ages. Immigrants also are likelier to own businesses than U.S.-born workers, the institute found.

A 2016 study by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine found that generally immigration positively impacts long-term economic growth of the United States. And unauthorized immigrants collectively pay more than $11 billion in taxes a year — and on average, pay 2.6 percent more of their paychecks on taxes than the top 1 percent of taxpayers, according to a 2016 study by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy.

“There’s near-consensus among economists that immigration is good for the economy, that it grows the pie in a number of ways, that without immigration, the economy would, in effect, get choked off,” Spiro said. “Unskilled immigrants are willing to come to the U.S., because they will make more here — in some cases, much more — than they would back home, even if they’re making less than what an existing U.S. worker would be willing to work for.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.