Sanctuary cities come under fire from Toomey, Pa. legislature

Listen

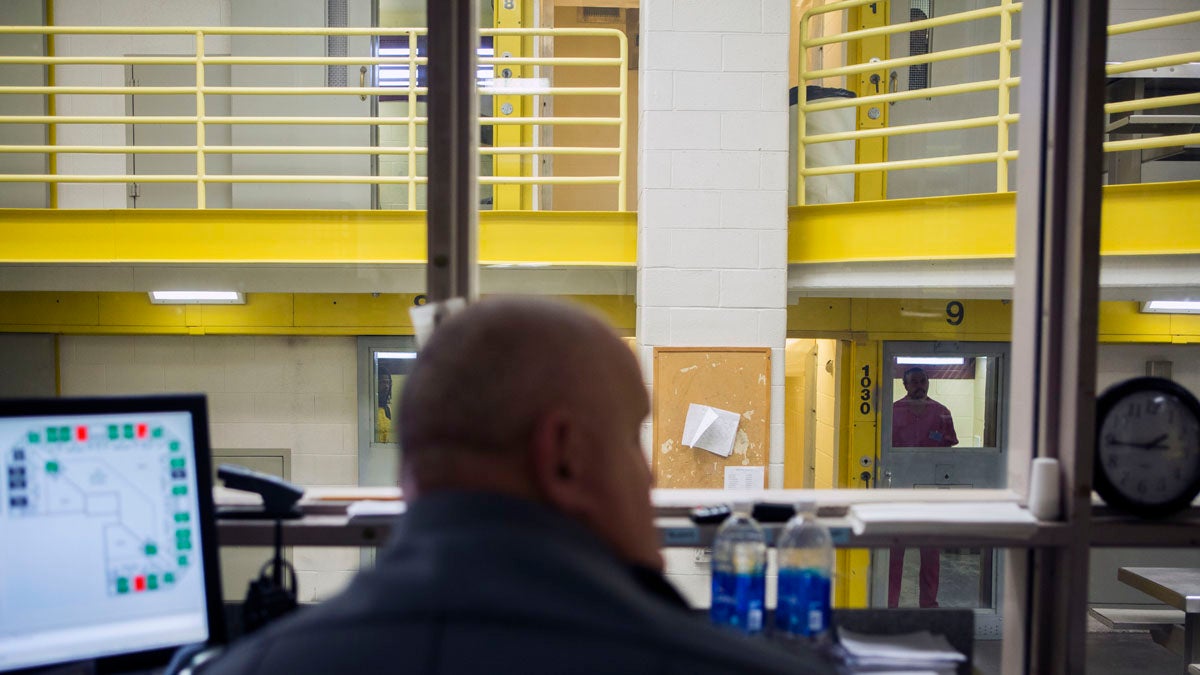

Corrections Officer Gregory Kulp monitors inmates at Lehigh County Jail in Allentown

Honoring or ignoring ICE detainer requests is a hot topic in Pennsylvania this election season.

When an immigrant living in the United States illegally gets arrested, the federal Immigration and Customs Enforcement Agency may issue a detainer request for that person. Detainers ask that the local jail hold that person for up to 48 hours until ICE has a chance to come pick them up.

Sanctuary cities — or counties, since counties run the jails in Pennsylvania — are places where officials refuse to detain immigrants after they have made bail or their charges are dropped. For Senator Pat Toomey, this is a problem.

He recently held a press conference on the issue in Philadelphia, saying, “this is not about immigration, it’s not about the politics of immigration. It’s about public safety. It’s about common sense. It’s about all of our security.”

Criminals on the loose?

Toomey has some pretty horrifying examples of ignored ICE detainers gone wrong. The latest is the case of Ramon Aguirre-Ochoa, who had been deported in 2009 but was arrested in Philadelphia in 2014 on charges of domestic violence. The charges were dropped and Philadelphia released Aguirre-Ochoa, despite an ICE detainer request in his name.

Then, this summer, Aguirre-Ochoa was charged with raping a 13-year-old girl. He’s currently sitting in jail awaiting trial.

“This is one of the most heinous crimes that it is possible to commit,” said Toomey, not accounting for the fact that Aguirre-Ochoa was charged, not found guilty. “It should not have been possible, and it would not have been possible, but for the fact that Philadelphia is a sanctuary city.”

Toomey’s “Stop Dangerous Sanctuary Cities” bill failed in the U.S. Senate in July. But now the Pennsylvania legislature has picked up the issue. The House passed a bill this week that would provide disincentives to being sanctuary counties by making them liable for the cost of crimes committed by immigrants here illegally.

“The sanctuary municipality is to be held liable for damages due to an injury to persons or property as a result of criminal activity by unauthorized aliens,” said Martina White, a Republican from Philadelphia and the author of the bill.

The senate will be considering the bill this week.

Sen. Pat Toomey, R-Pa., arrives for a news conference, Monday, May 9, 2016, in Philadelphia. Toomey called on Philadelphia to end its sanctuary city policy and to begin cooperating with federal law enforcement officers in helping them find immigrants in the country illegally who are suspected of violent crimes. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)

Sen. Pat Toomey, R-Pa., arrives for a news conference, Monday, May 9, 2016, in Philadelphia. Toomey called on Philadelphia to end its sanctuary city policy and to begin cooperating with federal law enforcement officers in helping them find immigrants in the country illegally who are suspected of violent crimes. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)

Philadelphia and beyond

Both Toomey and White focus on Philadelphia when going after sanctuary cities. One of Mayor Jim Kenney’s first actions in office was making Philadelphia a sanctuary city, a title he’s very proud of.

Philadelphia is a sanctuary city in the most traditional sense. Though there is nothing a city can do to stop ICE from arresting people within city limits, sanctuary cities don’t do anything to help achieve those ends. City officials do not honor ICE detainer requests unless they come attached to an arrest warrant, and won’t notify ICE if they find out someone they have in custody is in the country illegally.

But all of this legislative activity aimed at Philadelphia may catch other Pennsylvania counties in its wake, like any of the 32 counties sitting in a sort of sanctuary county middle ground.

Look at Lehigh County, which director of corrections Ed Sweeney says is “nowhere near what a sanctuary city is.”

They send fingerprints of all inmates to ICE and will notify the agency when they are preparing to release a prisoner. They’ll even help ICE pick that person up at the door to the jail. They’ll do everything they can to help ICE … almost.

“We will not detain somebody for any period of time if there is not a supporting judicial order,” says Sweeney.

Ed Sweeney, director of corrections for Lehigh County, at the Lehigh County Jail in Allentown, Pennsylvania on October, 20, 2016. (Jessica Kourkounis for Keystone Crossroads)

Ed Sweeney, director of corrections for Lehigh County, at the Lehigh County Jail in Allentown, Pennsylvania on October, 20, 2016. (Jessica Kourkounis for Keystone Crossroads)

Good for the taxpayer

Sweeney says this policy has nothing to do with protecting illegal immigrants and everything to do with protecting the taxpayer. Which is a lesson Lehigh County learned the hard way, when Ernesto Galarza was arrested in 2008 on drug-related charges.

Galarza made bail, but based on an ICE detainer, was kept in jail for an entire weekend. As it turns out, though, Galarza was not an illegal immigrant. He was an Allentown resident born in New Jersey. He sued ICE for issuing the detainer request and also sued Lehigh County, even though, as Sweeney says, they thought they were just following orders.

“If that immigration agent has made a mistake, then the county or city is therefore on the hook for any associated costs or litigations,” said Sweeney.

In 2014, a third circuit court judge ruled on Galarza v. Lehigh County. This ruling set national precedent that ICE detainers should always be treated as requests, not orders. Counties can honor them, ignore them or require further documentation, such as an arrest warrant or a judicial order.

Ernesto Galarza, an American citizen, sued ICE and Lehigh County after he was held in jail based on an ICE detainer in 2008. He was arrested on related charges and had made bail. (Image by Marco Calderon/ACLU-PA)

Ernesto Galarza, an American citizen, sued ICE and Lehigh County after he was held in jail based on an ICE detainer in 2008. He was arrested on related charges and had made bail. (Image by Marco Calderon/ACLU-PA)

A melting of the ICE

As a result of that lawsuit, ICE began changing its policies as well. In 2008, when Galarza was arrested, detainer forms used words like “required” to indicate a county’s responsibility when it came to detaining people on behalf of ICE. Now, those forms stress that this is “voluntary action” on the part of the county.

In 2014, ICE changed it’s detainment program to an initiative called the “Priority Enforcement Program,” or PEP. PEP splits ICE requests into two categories — request for notification and request for detainment.

ICE officials say in most cases, they just want to be notified when jails are preparing to release someone they want to pick up, keeping counties out of the business of detaining people after charges are dropped or bail is met. PEP is also supposed to narrow ICE’s focus to go after only those people who are proven to be a criminal threat. Just being in the country illegally is not enough to have a detainer issued against you.

“So if someone is just here illegally and they commit a crime and they’re inside a jail, because they don’t have a conviction, I’m not able to place a notification or detainer on that person,” said Pennsylvania Field Office director Thomas Decker.

For example, ICE would not have been able to issue a detainer for Ramon Aguirre-Ochoa in Philadelphia, because the charges were dropped. No conviction. But that’s not to say they wouldn’t have tried.

“One of the issues with ICE is what happens on the ground and what is said on the national level are often not the same thing,” said Sundrop Carter, of the Pennsylvania Immigration and Citizenship Coalition.

A 2016 Syracuse University study found that PEP was not living up to the hype. ICE is still issuing detainers on immigrants without criminal convictions as often as they were before that rule went into place. And despite the notification option, four out of every five requests from ICE are detainers, the more extreme option.

A fork in the road

All of that to say, counties in Pennsylvania don’t have much motivation to change their ICE hold policies just yet. But that could change if Pennsylvania’s sanctuary cities bill becomes law.

If they continue to not honor ICE detainers right off the bat, counties could run the risk of being sued by victims of crimes committed by illegal immigrants. But if they do honor those detainers without requiring an additional judicial order, they could be sued for improperly detaining a legal resident.

For 32 counties in Pennsylvania, walking a middle road may not be an option much longer.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.