Review: The questions surrounding ‘Equivocation’

Listen

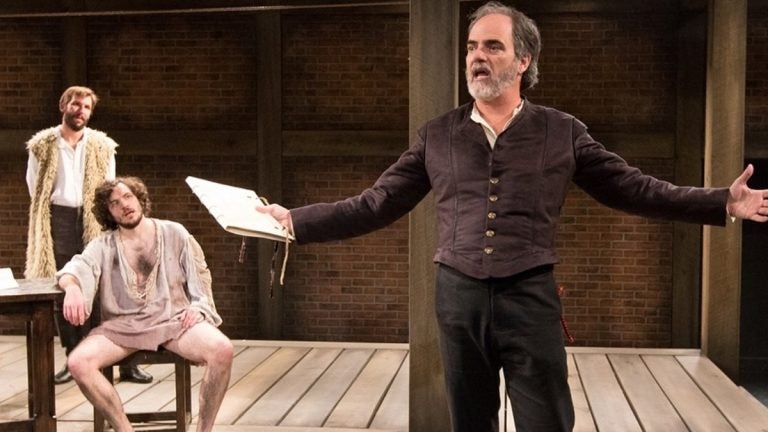

In Arden Theatre Company's production of 'Equivocatiopn,' from lweft: Dan Hodge, Sean Lally and as Shagspeare, Eric Hissom. (Photo courtesy of Mark Garvin)

Ask me what the play “Equivocation” is about and I could give you lots of answers, including God, souls, religion, politics, theater, acting … and more! Bill Cain’s play, about a man named William Shagspeare who’s forced to write a drama celebrating the British crown, is a sprawl of ideas.

That would be great if the ideas were somehow knotted together into a powerful concept, or if they were at least thought through. But “Equivocation” – in an Arden production with indisputable first-rate performances – left me feeling like a gate-crashing witness to history: I was there with all the invited guests, but not sure what I was supposed to be seeing. Cain asks his audience to understand 17th-century British history from the context of his characters’ dialogue, yet the lines they utter frequently sound like inside baseball… er, cricket. As a result, it’s as hard to work your way into “Equivocation.”

Even the Arden’s artistic guru, Terrence J. Nolen, can’t rein “Equivocation” in, with its plot that wanders toward one character we don’t meet until the play is long into its indulgent run of nearly three hours. But Nolen has an adroit command of the play’s most dramatic scenes, particularly an execution that comes at the end of the first act and some tense interchanges that, somewhere along the line, will further the plot. It’s the production’s theatricality – and not the play itself — that makes it admirable.

The above-mentioned character who belatedly becomes the plot’s center is Henry Garnet, a Jesuit priest who in real life heard about the Gunpowder Plot, in which a cadre of Catholics would dig a tunnel under Parliament, move in 36 barrels of gunpowder and plan to light them on Nov. 5, 1605. Practicing Catholics in Britain were heretics in this period after the Reformation, which gave Protestants (and, more to the point, members of the court) their Church of England. Under the rule of King James, Catholics could be executed. Henry Garnet was in double trouble. He was a Jesuit priest. He was also considered a Gunpowder Plot participant who used the confidentiality of his priesthood as a shield so that he wouldn’t spill the beans.

This concept – a philosophical notion of equivocation – is a way to tell the truth and lie at the same time, particularly when lives are at stake. Jesuits at the time were associated with the notion of equivocation, or failing to be openly truthful in order to serve the greater good. Almost every character in Cain’s play equivocates for some reason and, indeed, lives are at stake. King James, through his surly and self-righteous undersecretary of state (Dan Hodge) orders a popular playwright (Eric Hissom) to write a play glorifying the crown’s role in exposing the Gunpowder Plot. If the playwright, whose troupe receives James’ patronage already, says no – well, there’s always spare footage on the rack.

The playwright – he’s supposed to be William Shakespeare — cannot come up with a play and engages in many confrontations about it with his daughter (Campbell O’Hare), his actors (Hodge in dual roles, as well as Ian Merrill Peakes, Sean Lally and Anthony Lawton) and with himself. Problem is, something smells fishy about this Gunpowder Plot and the king’s reasons for wanting the play.

Maintaining that he needs research to write his characters, the playwright becomes a reporter – he travels to the Tower of London with the king’s permission, to interview some of the so-called plotters who remain alive there. This leads him eventually to Garnet, the Jesuit priest, and it also leads him to question whether the Gunpowder Plot was exactly what the government makes it out to be.

Cain’s play is one of a sheath-full that explores William Shakespeare as a person or uses his storytelling style and some of his language to execute a plot. (Two such plays are enjoying big audiences on Broadway currently.) There’s plenty of vernacular in “Equivocation” and plenty of Elizabethan language, too, and the mix works well. It’s telling, though, that the standout material comes toward the end, when the dialogue includes much of Shakespeare’s own.

The big mystery to me is Shagspeare himself – if Cain is creating a history around Shakespeare, and includes Shakespeare’s text, why does he use the cutesy name and not the real one? All the historical figures in the play are real, no names changed there. And so “Shagspeare” (or “Shag” as he’s called in a sophomoric double entendre among the program’s list of characters) is a distraction in a play that demands attention to its knotty unfolding. It’s also an act of theatrical identity theft; oddly, if Cain had used the real name we could see the play as a reasonable allegory. As it is, creating a Shagspeare for the real thing – and peopling the play with actual historical figures — makes us wonder how seriously we’re to take this drama offered up with such gravitas.

Cain is a playwright, screenwriter (“Sounder” and others), director, actor — and a Jesuit priest. His play “How to Create a New Book for the Bible” was produced earlier this year by People’s Light in Malvern, and I admired it for its clear theme that everyone has a family history, a story that’s a sort of personal Bible. If only that clarity carried over to “Equivocation,” which has pieces of a good tale in there, somewhere.

“Equivocation” runs through Dec. 13 at Arden Theatre Company, on Second Street just north of Market Street. 215-922-1122 or www.ardentheatre.org.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.