Residents discuss capping Vine Street Expressway, other remedies at U.S. DOT forum

Barrier. Obstacle. Divider.

Nobody at last week’s Every Place Counts meeting had anything nice to say about the Vine Street Expressway when asked for one-word descriptions of the submerged highway.

But everyone in attendance, from Mayor Jim Kenney and his staff, to representatives from Philadelphia Chinatown Development Corporation (PCDC) and community activists, to PennDOT and U.S. DOT staff signaled optimism that the Expressway’s worst impacts on the neighborhood could be mitigated through interventions of varying intensities and price-tags.

As PlanPhilly reported a few weeks ago, four cities were selected through U.S. DOT’s recent Every Place Counts competition to host an intensive two-day workshop focused on areas severely impacted by federal highway infrastructure, attended by local, state, and federal decision-makers and technical experts. (Notably, the Congress for the New Urbanism, which has long advocated for highway teardowns, is consulting on this initiative providing technical expertise.)

And so it was that local officials spent all day last Thursday trudging along an unshaded Vine Street in the sweltering July heat, taking in the landscape at its most brutal. The first part of the day was limited to decision makers and experts, and there was a meeting in the evening for community members to offer their feedback, followed by another public meeting on Friday afternoon where some initial design concepts were presented.

In his remarks at the first meeting, Mayor Jim Kenney called the Expressway “monstrous” and jokingly referred to it as “the not-so-great wall of Chinatown.” While not calling explicitly for a full cap, he said changes were needed to increase mobility for residents of Chinatown and Callowhill, to stimulate job creation north of Center City, and to create more public spaces and improve access to existing ones like Franklin Square.

Councilman Mark Squilla was more explicit about his interest in working toward a full cap, saying that covering or capping the Expressway would be “a great opportunity…to make it more accessible for people on both sides of Vine Street” and “to build private development and interest in this area because [investors and developers] know something’s going to happen.”

Capping the Expressway has long been a priority for PCDC, and that position appeared to have near-universal appeal among the sixty or so attendees of the public meeting on Thursday.

“It was good to continue the conversation that we’ve been having for 50 years now, and to update it and prepare ourselves for the future planning processes that are right around the corner,” said Sarah Yeung, Director of Planning at PCDC, “I think the valuable part was having all the decision makers in the room, and having the spotlight cast on this section.”

Yeung was referring to the Chinatown neighborhood plan that PCDC will embark on this year, and which they expect to hire a consultant for later this month. The eventual report and recommendations from U.S. DOT will most likely be folded into that plan and refined through deeper community engagement.

Funding a full or even partial cap would be costly to say the least. But one of the presenters, Peter Park, formerly the chief planner for Milwaukee and Denver, ran through a number of different scenarios for local revenue streams that could complement state or federal funding, such as a tax-increment financing (TIF) district, value capture from nearby private land, or capping the cuts with buildings through some type of air rights deal. One example project in Columbus, OH featured a partial cap of a submerged highway, obscured by buildings fronting the highway bridges.

This option was one of the more popular ideas, judging from the audience feedback, though attendees gave a variety of suggestions. Some preferred tall buildings, and others shorter ones like in Columbus. Some audience members preferred to see a park or open space in place of the cuts, citing the dearth of parks besides Franklin Square, and some preferred a mix of buildings and green space.

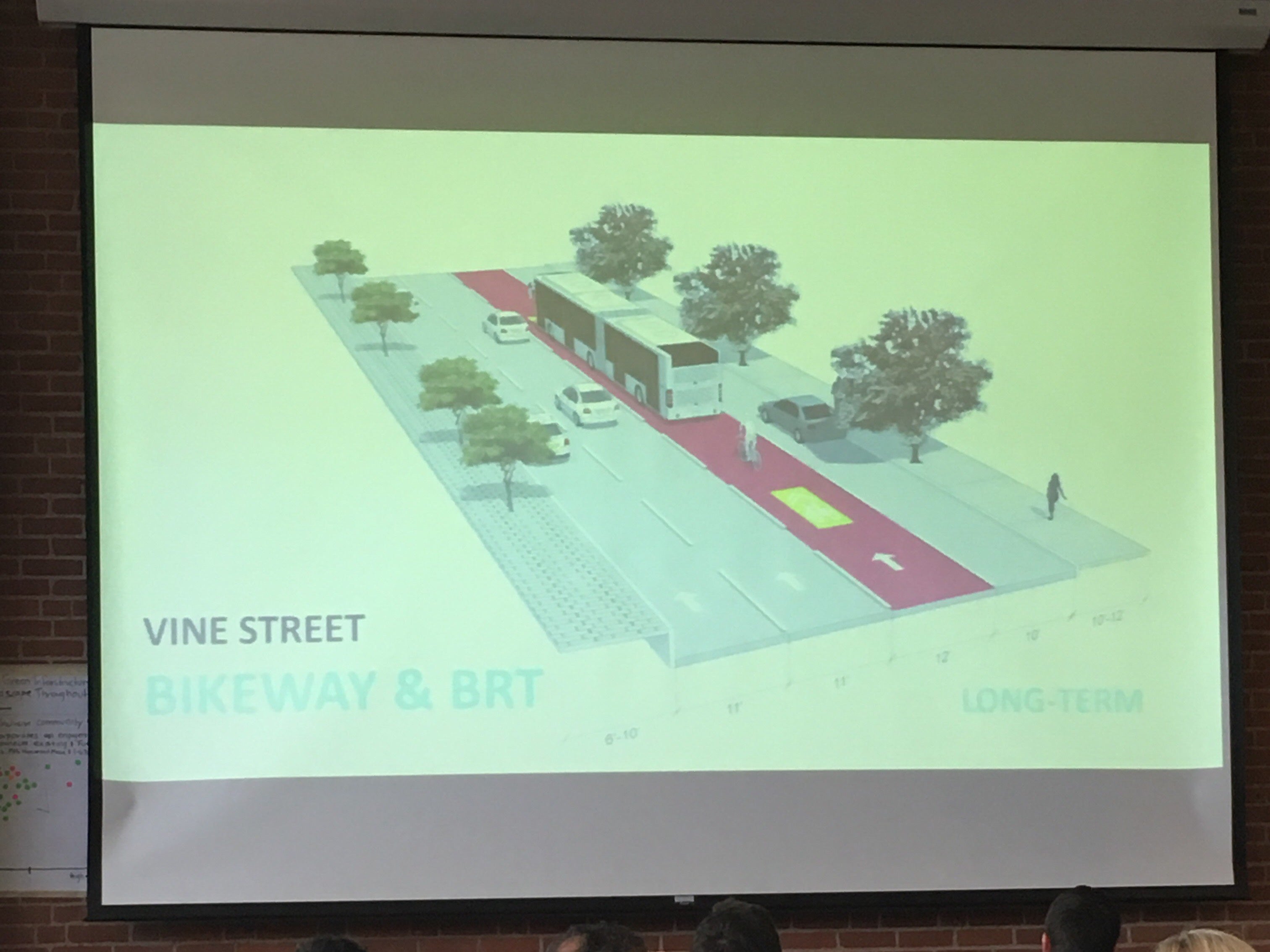

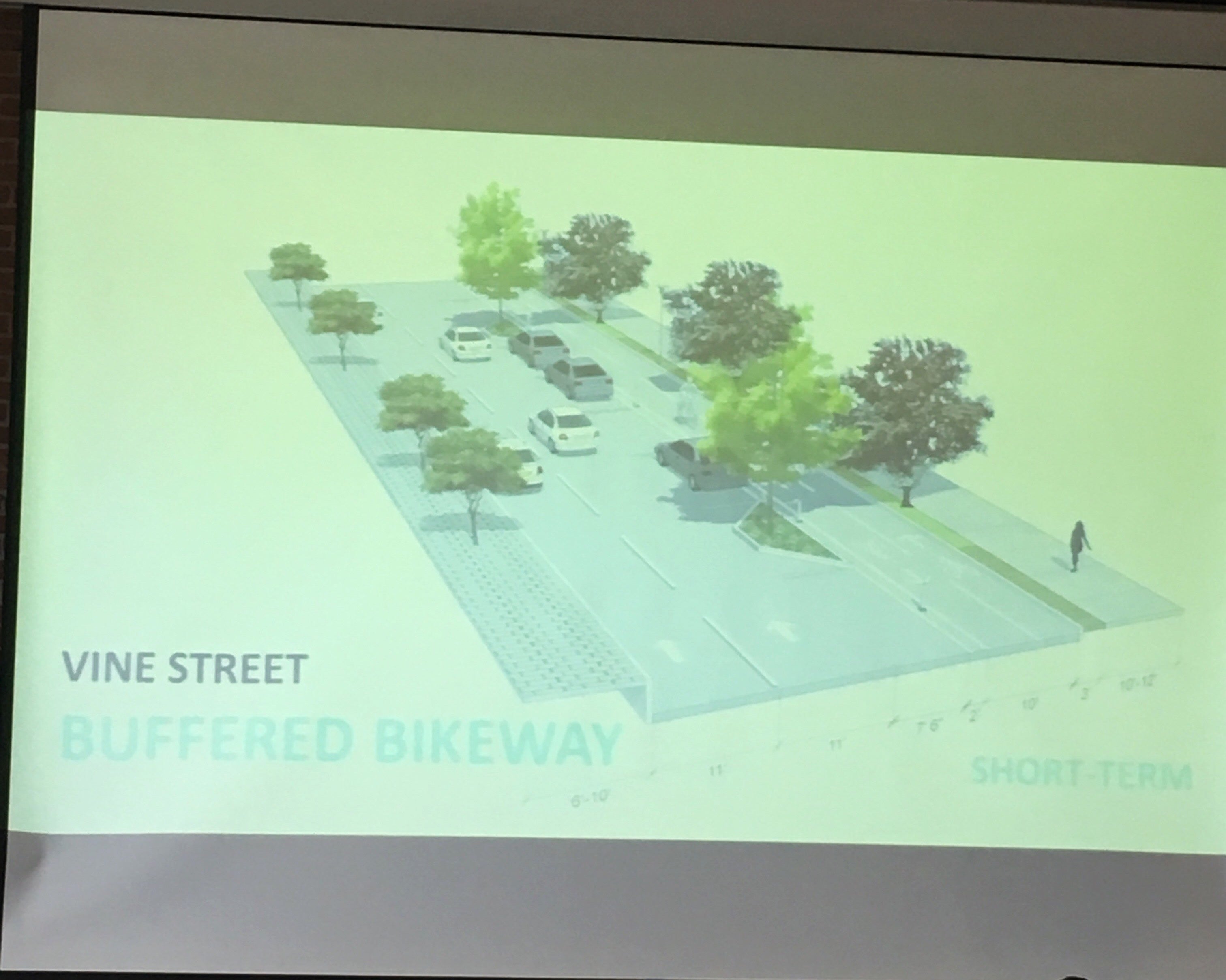

There was also a wide-ranging discussion and less consensus about changes to the intersections and at-grade service roads, also called Vine Street, running parallel to the Expressway. Some wanted to see those streets narrowed with traffic calming features to support bike lanes and pedestrian amenities, while others preferred the current auto-oriented configuration, complaining about rush hour congestion.

The outcome of the two-day charrette will be a report by U.S. DOT that incorporates community feedback and different concepts for short- and long-term changes to tame the effect of the Expressway and at-grade service roads along it.

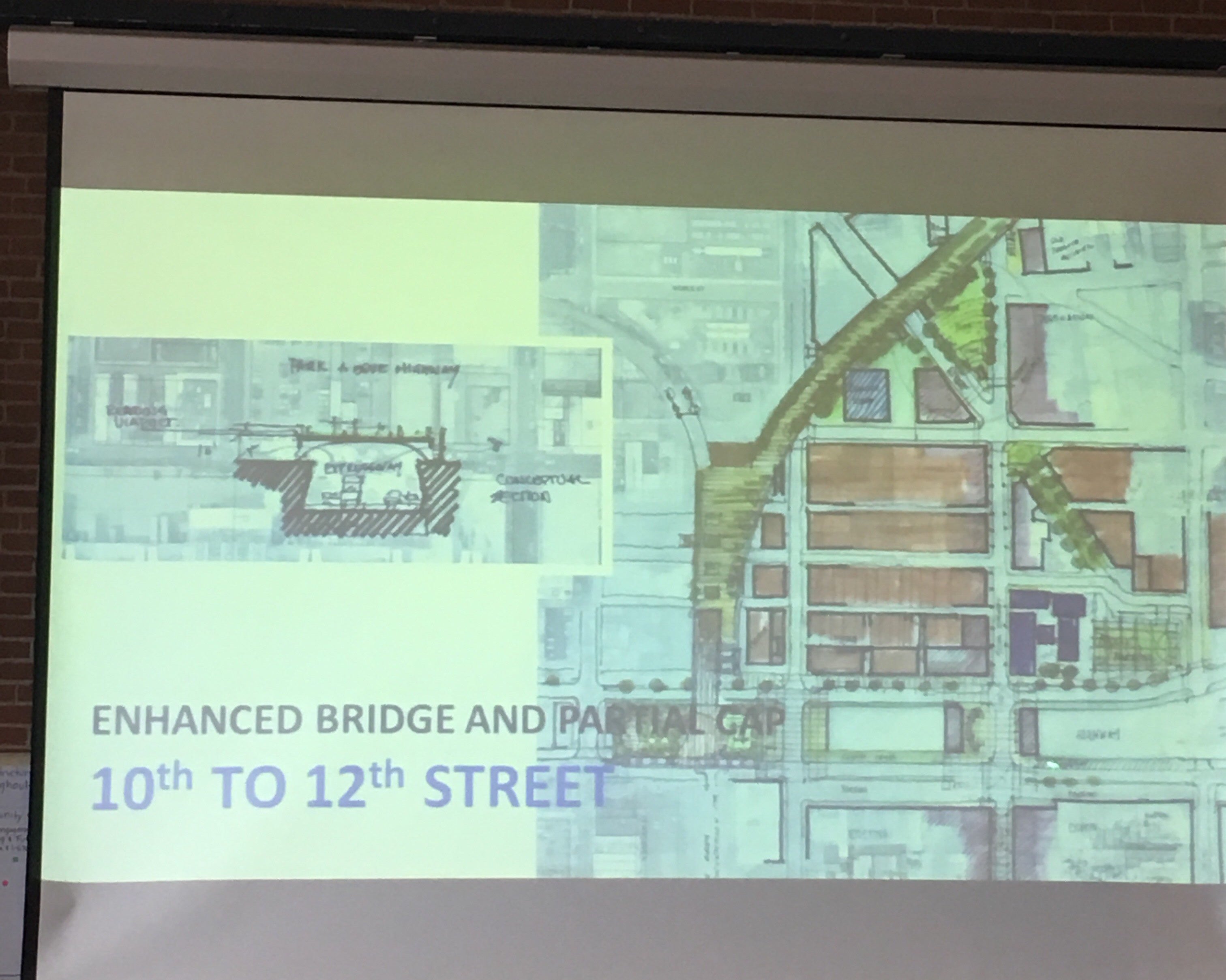

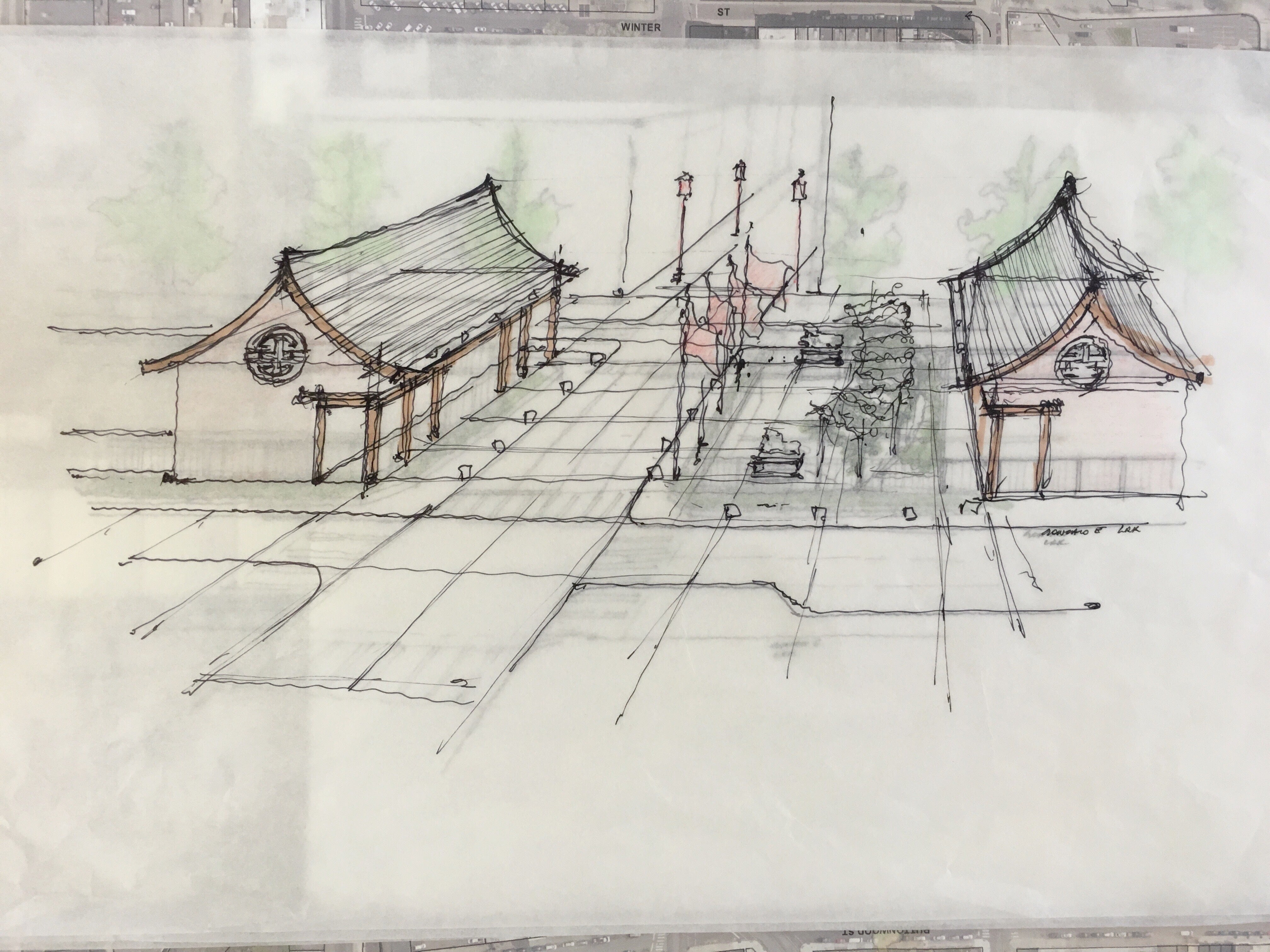

Among the ideas shared: curb bumpouts at intersections to shorten crossing distances, particularly at 10th Street; parking-protected bike lanes on Vine Street in place of the third travel lane; replacing another travel lane with a dedicated bus lane; a partial cap with commercial buildings fronting 10th Street; a partial cap with play spaces on either side of 10th Street, using public art as a noise barrier; a full cap between 10th and 12th Streets with a pedestrian bridge extending from the end of the future Rail Park across Vine Street.

“There’s no really good play space around the area, so the idea here was to cap the highway a little bit, and create a public space that could be a playground for the kids,” said Gonzalo Echeverria Halley-Harris of LRK Architects, a charrette volunteer who helped develop conceptual images. ”We came up with this idea for a dragon that’s protecting the kids, and also takes the noise from the surroundings.”

Already, the Streets Department is thinking about short-term changes that can be made, such as the timing of lights and pedestrian crossing signals.

“The walking tour actually resulted in some observations of some timings that didn’t make sense, and it looks like probably next week, a number of those timings will get fixed because we can look and see what’s going on,” said acting Streets Commissioner Mike Carroll. “I have a sense that a lot of the frustration and anxiety people have getting from one side to the other is probably going to get address when we fix the signal timing.”

Carroll also mentioned curb bumpouts, green infrastructure, and protected bike lanes as possible projects that could potentially be undertaken within the next five years.

“These bump-outs are so popular around the country that there are now manufacturers who make temporary bump-outs,” he said, “So maybe this is a location where we could pilot something like that.”

PennDOT controls the whole area around Vine Street, including the service roads and the subterranean Expressway, so it is substantially in the driver’s seat when it comes what changes may or may not be considered.

PennDOT’s District 6 manager, Chuck Davies, seemed to struggle with how PennDOT would respond to essentially a fundamental critique of the highway. By the agency’s metrics, the Vine Street Expressway is still a project that checks all the boxes.

“This highway isn’t like I-95 or parts of I-76 that was built before the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). Its impacts were largely addressed at the time, in the best way people thought possible, and these are still the regulations under which we operate,” he said, “And so now you have other concerns being brought that are very real, but I think some of the things that are being articulated are not always easy to work into the bureaucratic process.”

“The disconnectedness is an impact that is difficult to explain within the context of the bureaucratic process,” he continued, “but we have to do that. The neighborhood has changed, so it’s important to address that.”

Chinatown community members would probably say it’s less that the neighborhood has changed, than that the transportation planning profession’s values have changed to become more responsive to communities’ concerns in the decades since the Expressway was built.

The Every Place Counts initiative is evidence of that, with its emphasis on empowering affected communities, and changing the culture around transportation planning at state DOTs.

“This is about you letting us know what you’re looking for, and us using our expertise to help you think of ways to achieve that vision,” said Stephanie Jones, Senior Counselor to DOT Secretary Anthony Foxx, “This is us learning what your needs are–what works for you, what doesn’t work for you. How we can better engage with you in the work that we’re doing?”

The city charrettes are also a learning opportunity for U.S. DOT, she explained, as the department plans to incorporate observations from running the meetings into a best practices guide on community engagement.

U.S. DOT is planning to develop a new Transportation Community Academy that will help residents around the country better understand the transportation planning process, and get involved at earlier stages so they can participate more meaningfully. The Every Place Counts meetings will help build the curriculum for that initiative.

She also stressed the community’s central role in getting local leaders and elected representatives to move forward with the concepts discussed at the forum. Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission, PennDOT, and the City of Philadelphia will have to prioritize projects in terms of timing, cost, and impact, with the goal of eventually getting them onto the transportation work plan, but even before that, some neighborhood-level efforts will be required to put some specific projects on the agenda.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.