Researchers find 96% accuracy in strips that detect Fentanyl in street drugs

New research suggests that a simple, fentanyl-detecting tool can provide accurate information that may help drug users protect themselves from an overdose.

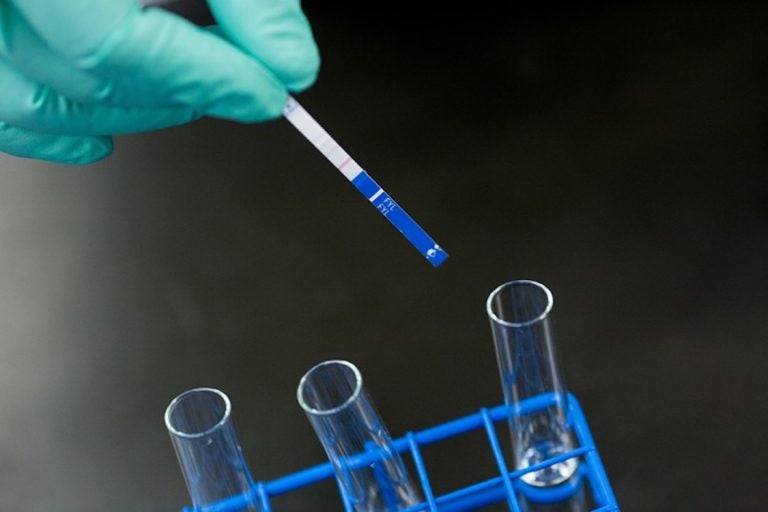

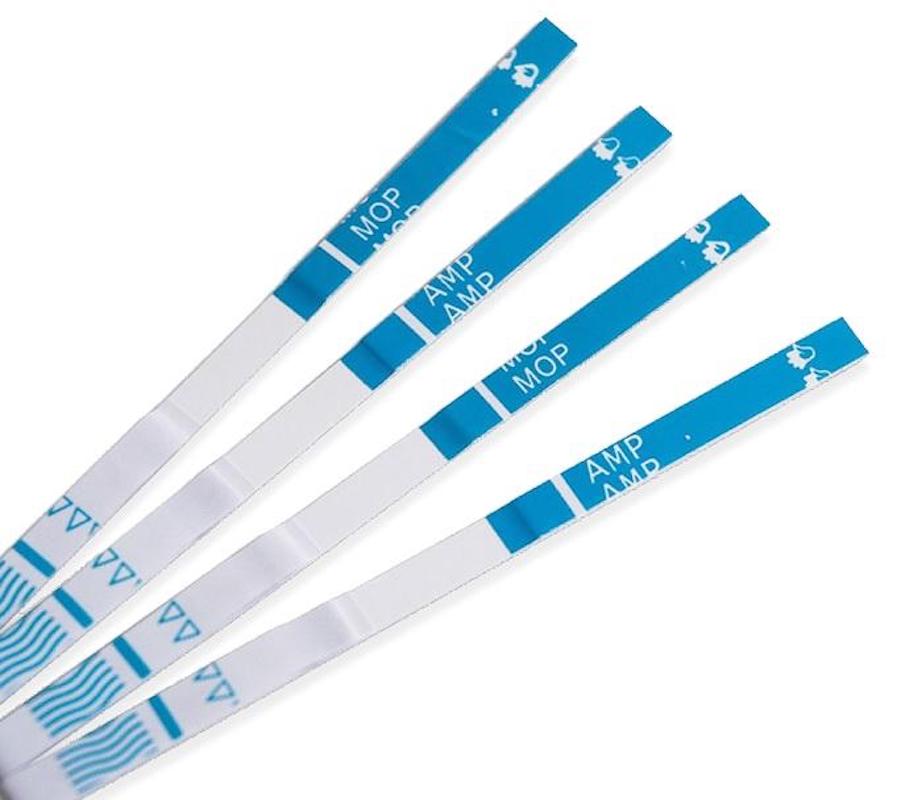

Fentanyl testing strips (JHU BLOOMBERG SCHOOL OF PUBLIC HEALTH/BLOOMBERG AMERICAN HEALTH INITIATIVE)

New research suggests that a simple, fentanyl-detecting tool can provide accurate information that may help drug users protect themselves from an overdose.

Researchers at Johns Hopkins University and Brown University tested the accuracy of three methods for detecting the presence of the potent opioid, using over 200 street drug samples that came from police departments in Baltimore, Maryland, and Providence, Rhode Island. They found that small plastic strips that can be dipped into a solution of the drugs mixed with water gave more accurate results than two high-tech machines that scan for chemical composition. In samples where fentanyl was known to be present, the strips detected it 96 to 100 percent of the time.

Checking drug content could add to existing methods for protecting people who are addicted to drugs like heroin, said Dr. Traci Green, an associate professor of Brown University’s schools of medicine and public health.

“We provide syringes, for instance, in drug injection to improve safety of how people use,” Green said. “But we don’t actually have a focus on the drug itself.”

Public health authorities say that fentanyl is a major driver of the recent surge in overdose deaths in Philadelphia and across the nation. It’s often cut into heroin and cocaine and consumed by unsuspecting users. In 2016, Fentanyl was detected in 412 of Philadelphia’s 907 overdose deaths.

The fentanyl testing strips are similar to a home pregnancy test, and cost about one dollar a piece. They were designed to test for fentanyl in urine samples, but some harm reduction workers around the country are already starting to use them to test the drugs themselves. Green said that some are teaching drug users how to do the tests on their own, while others offer it as a service available in a clinic setting. The supervised injection site in Vancouver visited recently by Philadelphia officials, Insite, provides the testing strips to drug users.

But the fentanyl-detecting tool hasn’t been incorporated into Philadelphia’s harm reduction efforts yet, said Elvis Rosado, the education and outreach coordinator at Prevention Point Philadelphia. Rosado said he is skeptical the city’s large population of homeless drug users would go to the trouble of testing.

“They’re using now in public,” Rosado said. “They don’t have much time to stop, check it, test it, and then go ahead and inject.”

Users would have to wait about five minutes for the results after mixing their drugs with water.

Green said the study doesn’t establish whether the strips would be able to detect all the different forms of fentanyl that could be present in drugs bought on the street, which could result in a false negative result. The device was able to detect two of these “fentanyl analogues” in the researchers’ tests, but Green said there are over a dozen circulating in the nation’s drug supply.

“That’s a really important set of questions for the scientific community to take on,” Green said.

Even in one batch of samples from Providence where fentanyl was known to be present, the strips gave a false negative 4 percent of the time.

But Green said the strips minimize concerns about false negatives given the high degree of accuracy the researchers found.

The study also suggests that many drug users might be willing to give the strips a try. It surveyed over 300 drug users and found that about 90 percent felt that checking what’s in their drugs would help protect them from an overdose.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.