‘Ransomware’ hackers taking files hostage as malicious software spreads

Listen

Alessia and her son Jared stand over her computer in grandmother Carmelina Mattioli’s house in Glassboro

Online thieves are embracing a growing trend in computer hacking called “ransomware,” in which a hackers take over a computer, encrypt the files, and demand payment for their release.

For the great many of us who use the internet, having our information stolen and sold to the highest bidder is a real fear.

But what if instead of stolen, your files were locked up, held hostage until you paid to have them released?

In fact, online thieves are embracing a growing trend in computer hacking called “ransomware,” in which a hackers take over a computer, encrypt the files on that computer, and demands money before decrypting the files.

“These folks are looking to get paid,” said Dave Weinstein, New Jersey’s first chief technology officer, of ransomware hackers, who typically are not motivated by political or religious ideologies.

And, these days, they are looking to get paid much more often.

Since the beginning of 2016, more than 4,000 ransomware attacks have occurred daily, according to the New Jersey Cybersecurity and Communications Integration Cell.

Last year the rate of ransomware attacks was only a quarter that size, averaging about 1,000 attacks per day, said the office.

“What’s changed is the volume of attacks is increasing exponentially,” said Weinstein, “and the tactics are becoming more sophisticated.”

‘My computer was beeping … and the screen went black’

In April, Glassboro resident Alessia Mattioli opened what she thought was a routine email from her professor at Rutgers University’s nursing school.

But when Mattioli clicked a link in the email, ransomware took over her computer almost immediately.

“My computer was beeping. It was going ER! ER! ER! And the screen went black. And it had all these words. It was like, ‘your computer’s been compromised, you need to call this number.'”

(The ransomware came in through an email that appeared to be from someone Mattioli knew and trusted, a common hacking method called “phishing.” But users can also get ransomware, for example, through infected websites or ads.)

Mattioli called the number on the screen, which claimed to be for an Apple technician, but something seemed wrong when she got through to the man on the other end.

“He was like, ‘We’re gonna charge you $400 for this, $250 to wipe out your WiFi,” she said. “It almost was over $1,000. I was like there is no way this is real.”

Hackers are not always so cagey — often they will tell users outright that they have taken their files hostage and will only release them in exchange for money.

Many cybersecurity experts encourage ransomware victims to decide whether to pay based on several factors, including the amount demanded and the sophistication of the encryption.

But sometimes paying up is the only way. The Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3), a unit of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, calculated that victims paid more than $1.6 million to ransomware hackers in 2015. Because the actual number of ransomware attacks is likely much higher than the number reported, the amount paid to hackers is also probably much higher.

Hackers attack individuals, public institutions, and private companies alike, and often they demand several hundred dollars. Occasionally the ask is much higher. A hospital in Los Angeles recently paid about $17,000 to unlock its computer network.

Hackers also typically request payment in bitcoin, a difficult-to-trace digital currency, which can be tough to obtain for the less computer savvy.

No problem, said Seth Danberry, president of the Newark-based cybersecurity firm Grid32. “[Hackers] essentially have customer service to handle that type of situation,” he said.

Danberry said the organizations that carry out ransomware attacks, mostly operating out of Asia and Eastern Europe, “are pretty sophisticated. They will actually help you acquire bitcoin and get it to them. They will walk you through it.”

The best defense is a good defense

Last year, New Jersey and Pennsylvania had among the highest rates of cyberattacks in the U.S., according to IC3.

One was a ransomware attack that shut down the Swedesboro-Woolwich School District in Gloucester County for a few days in March.

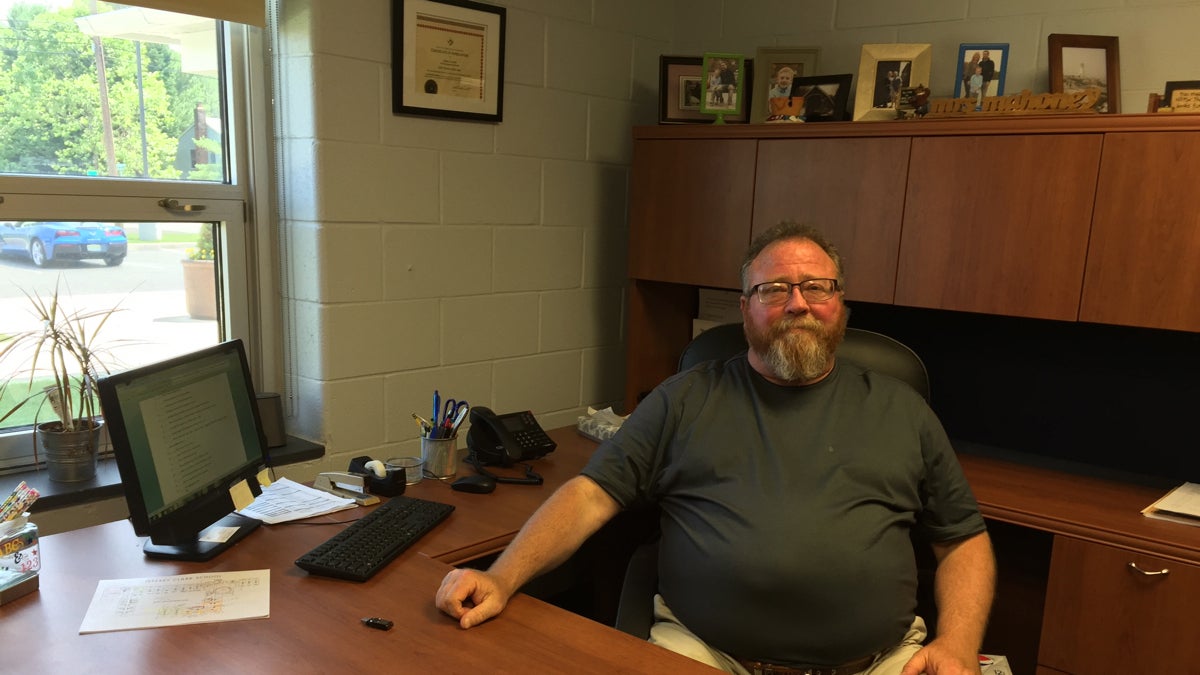

Terry Van Zoeren was interim superintendent at the Swedesboro-Woolwich School district during a ransomware attack. (Joe Hernandez/WHYY)

Terry Van Zoeren was interim superintendent at the Swedesboro-Woolwich School district during a ransomware attack. (Joe Hernandez/WHYY)

Then-superintendent Terry Van Zoeren said it disabled the school’s cameras and security system, locked student and parent information, and even hampered lunch period.

“Kids have pass codes they punch in and charge their lunch accounts into which parents prepay,” said Van Zoeren. “We couldn’t even open the cash registers.”

Hackers demanded the bitcoin equivalent of $125,000 from the district, which Van Zoeren and his colleagues refused to pay. Eventually the district recovered some files and rebuilt other parts of the network that never came back.

But the entire episode left employees emotionally rattled, a common side effect of a specific kind of computer hack that worms its way into users’ lives through their personal and work computers.

“It’s hard to get angry when you don’t know where to direct your anger,” said Van Zoeren. “It made us feel somewhat powerless.”

Experts say the best way individuals can defend against ransomware is to back up files somewhere outside their computers, such as an external hard drive or the cloud.

To fight the cyber phenomenon on a state level, however, has required the efforts of the N.J. Office of Homeland Security and Preparedness.

Weinstein said federal departments are focused on protecting national assets from cyberattacks, in a attempt to protect the entire country, but that ignores many smaller targets that would only affect state residents if disabled.

“There are a majority of assets within our state that fall below that very high threshold that, if impacted adversely, would not impact the nation as a whole,” said Weinstein, “but would certainly affect the residents and the businesses of the state of New Jersey.”

OSHP’s cybersecurity division, formerly helmed by Weinstein, also tracks of dozens of popular ransomware variants to better inform victims deciding whether to pay attackers.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.