‘Traumatized with good habits’: Delaware’s bold experiment to aid at-risk students

Listen

(Avi Wolfman-Arent, NewsWorks/WHYY)

Welcome to the vaguely militaristic, absolutely fascinating, and potentially game-changing world of UD Scholars.

This is the third story in our First Year, First Generation series. For an introduction, click here.

You can listen to Part 2, Part 4, Part 5, and Part 6 by clicking on the links.

It’s 6:45 on a Thursday morning in late August.

The University of Delaware’s main campus in Newark is still, save for a group of ROTC cadets stretching in a circle on one of the college greens.

Inside the first-floor common room at Gilbert Hall, a group of students greet each other with talk of the latest movies and music. If not for the time of day, this could be a club meeting. Or a study session.

Then the idle chatter breaks–and the chanting begins.

“What is today,” shouts a slight young man with frosted curls.

“A new beginning,” reply 30 other students who have gathered around him in a semi-cricle.

“What is our mission?”

“Defining purpose through shared experience strength and hope!”

“Again!”

“Defining purpose through shared experience strength and hope!

“What will we become tomorrow?”

“SCHOLARS!”

“What will we become tomorrow?!”

“SCHOLARS!!!!”

The students applaud, gather their things, and march in unison out the door.

Welcome to UD Scholars

Welcome to the vaguely militaristic, absolutely fascinating, and potentially game-changing world of UD Scholars.

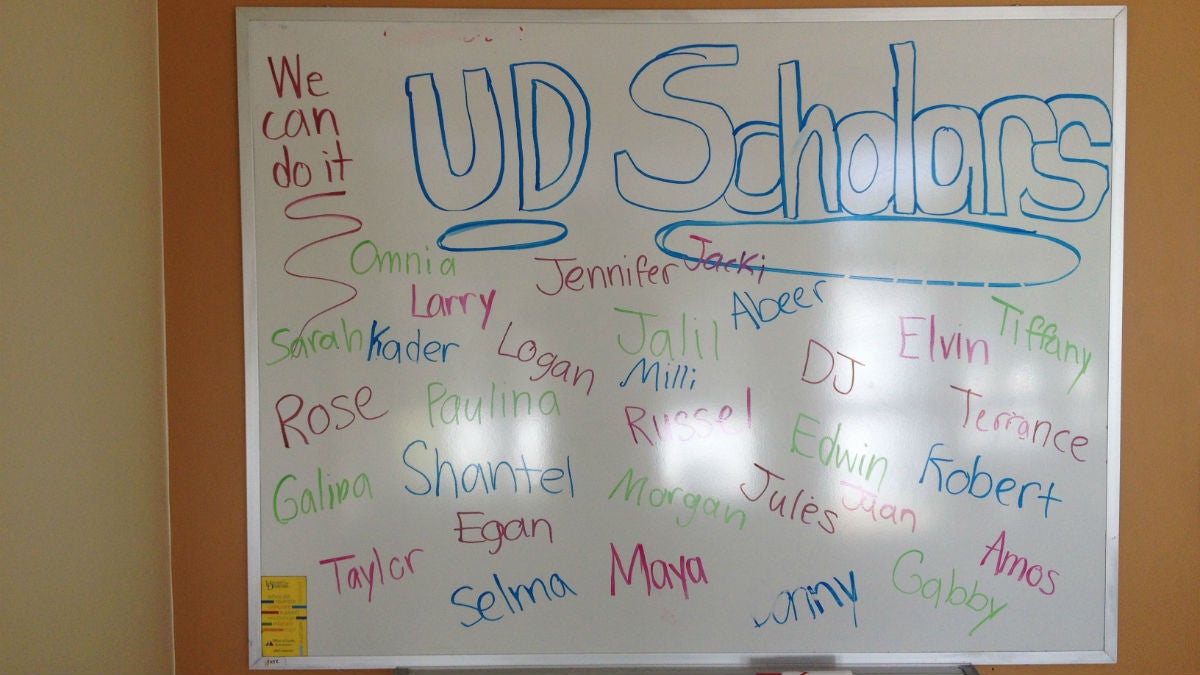

The throng of chanting students is comprised of incoming freshmen. They are all either students of color, first-generation college students, or low-income students—often all three. None of them quite had the high school GPA or SAT scores to get into the University of Delaware’s main campus, but after an interview they were given a second chance–a conditional acceptance. The condition is that they complete a two week orientation right before classes begin in late August.

That orientation is, in a word, intense.

Students wake up around six every morning, setting in motion a tightly choreographed blitz of activities that doesn’t end until 11 at night. They travel together from class to class. They eat together. They study together. They must walk everywhere “with purpose” (a euphemism for “walk really, really fast”). They cannot allow any gaps to emerge in their traveling herd. Stragglers are a serious no-no. Once in class, they cannot sleep, yawn, or slouch. They must participate in group conversation without participating out of turn.

Should they commit any of the above infractions they will receive a “write up” from one of the peer staff, a group of older students who control basically every waking minute of the scholars’ lives over these two weeks.

“We’re, like, traumatized with good habits,” says Jacki White, one of 31 students in this year’s UD Scholars cohort.

The students are repeatedly reminded that they haven’t yet been accepted to the university and that others on campus believe they shouldn’t have been given even conditional admission.

“Trust me, we’re reminded every single day,” says White. “There’s people in UD who don’t want the scholars program, who don’t want us here. They never even met us yet and they’re already like, ‘We don’t want them here.'”

They are told they can’t be normal college students. They must be paragons of intellectual ambition and classroom decorum. They must earn their way. They must be scholars.

“You’re gonna be surrounded by students who’ve come here to have that college experience and will want to convince you that–well, first and foremost you need to have a good time, that college is about having a good time,” says Doug Zander, the University of Delaware’s director of admissions. “No it’s not. College is about developing yourself as a scholar. The rest of it is marketing.”

A diversity problem with deep roots

And what is the purpose of all this tough talk?

Diversity.

The University of Delaware has disproportionately low number of black students. Of the over 17,000 undergraduates who enrolled at the University of Delaware’s flagship campus in Newark last year, just 5.1 percent were African-American. This in a state where 22 percent of the total population is black.

Noted civil rights attorney Louis Redding had to sue the school in 1950 before it would admit a black student, and UD has long been perceived as the privileged white counterpart to Delaware State University, a historically black school and the state’s only other public, four-year university. In the last year alone, local civil rights leaders and politicians have blasted the school for its seemingly stalled attempts to diversify the campus both racially and socioeconomically.

UD Scholars started last year and has been framed as a potential solution to the school’s diversity woes. It’s based on a similar program Zander helped start five years ago at Millersville University in Pennsylvania.

A new approach to admissions

The program is, in a sense, an admission of what selective schools like the University of Delaware cannot do. They cannot magically summon more minority students with high SAT scores and GPAs. They cannot, Zander believes, admit under-qualified students and erase their academic shortcomings in the short time between when they are admitted and when they matriculate.

But the university thinks it can change the way under-qualified students approach college, ensuring they have the resilience and sobriety to process failure and persevere. It all starts with this two-week indoctrination in “scholarly” behavior, an indoctrination that can look harsh.

“I remember the first night I saw this. I just thought, oh, I didn’t really expect it to look like this. This feels mean. I can’t do this,” Zander says.

What swayed Zander were the results. At Millersville, first-year retention for these at-risk students increased 20 percentage points. Of the 33 students in Delaware’s first UD Scholars cohort, 30 returned for their sophomore years. That 91 percent retention figure is almost exactly the same as the university’s overall rate of return.

To be clear, it’s not like the scholars spend the day doing military drills. Most of the time they’re in classes or info sessions. Some of the content is academic, but most of it is about connecting them to campus resources or teaching them about squishy concepts like grit and perseverance.

In one session they learn about how to seek leadership roles on campus. In another they take a “resilience self-assessment” and learn about methods to enhance their resilience in the future. They’re told repeatedly that they should seek academic help, and reminded where they can go on campus to find it.

Like “going through marine training”

What distinguishes the program, though, is its disciplinary structure.

“This program is so stringent it’s kind of like going through marine training and then sending somebody in the real world,” says Brandon Jackson, a graduate student who helps coordinate the program. “When they get into matriculation in September it’ll be easier. They’ll go for that culture shock now with all this support around them and not by themselves in September when they’re thrown to the wolves.”

The students regard UD Scholars with a mix of chuckling disbelief and reluctant appreciation. They describe their orientation alternatively as “like…an ROTC program” and “a jail program”–but always with a laugh. When the two weeks ended, all 31 students had completed the orientation and earned their full acceptance to UD. And they all said they were glad to have done it, partly for the lessons imparted and partly because it had brought them closer together.

“At first I didn’t really feel like I belonged here because this is a predominantly white school,” says Amos Tarley, a freshman from Newark. “But the group that we have here is very diverse and it made me have hope that maybe this could be a place for me, because I just found 30 new family members. So I feel, like, very at home here.”

The program right now is in a pilot phase and costs the school approximately $5,000 per student. Zander hopes someday to grow the program to “a few hundred” students. Adding 300 or so minority and low-income students would make only a modest dent in the school’s diversity gap, but Zander believes it could “change the culture at the University of Delaware” and make the campus more attractive to under-represented groups.

Whether any of that happens–or whether UD Scholars becomes a model for other selective universities trying to encourage diversity–depends on how today’s freshmen fare over the next four years.

The students, for their part, say they’re ready.

“Keep an eye out,” says Tarley. “You’re gonna see a lot of scholars on the dean’s list. You’re gonna see a whole lot of scholars going to graduate school, getting their PhDs. Watch out University of Delaware.”

Indeed, the university will be watching.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.