Prison closures could be a boon to state finances, but communities are worried

Listen

Prisoners walk the yard at Camp Hill State Correctional Institution. The Pennsylvania Department of Corrections (DOC) announced five prisons were being considered for closure. Camp Hill SCI expects to hold more prisoners due to closures. (Lindsay Lazarski/WHYY)

The state has fewer inmates and more debt. The Department of Corrections says closing prisons is an effective way to cut costs.

It’s been three weeks since the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections (DOC) announced five prisons were being considered for closure: State Correctional Institutions Pittsburgh and Mercer in the western part of the state, and Waymart, Retreat, and Frackville in the east. More than 2,500 prisoners will be relocated to other prisons throughout the state.

Over the last two years the state’s inmate population dropped by nearly 1,600 people. That reduction allows the Department of Corrections to reshuffle inmates and shutter prisons.

Pennsylvania State Corrections Officers Association president Jason Bloom is apprehensive. The two closures will dangerously stretch prison capacity, as well as corrections officers’ ability to do their jobs, he said.

“You cannot continue to shove inmates, or stack them like cordwood, into institutions that are already over population. It’s a powder keg and you’re just walking around with a lit cigarette.”

Corrections Secretary John Wetzel said at a recent hearing in the Pennsylvania Senate that the remaining prisons will operate at 109 percent capacity. It’s not ideal, he said, but his department estimates it can save between $80 and $90 million. This year the state faces a $600 million budget gap. Next year, the number is $1.7 billion.

The Retreat prison is in the district of State Senator John Yudichak (D-Luzerne/Carbon). As far as savings go, the numbers don’t add up, he said.

“All the personnel costs, all the inmate care costs are transferred to another prison, you’re not going to see tens of millions of dollars being saved, matter of fact, you’re going to see overtime budgets go up. That’s exactly what happened when they closed prisons in 2013, the overtime budget spiked to $90 million.”

According to the DOC, the 800 staff affected by the two closures will have the opportunity to work at another state facility.

But communities worry their economies will be hard-hit.

Yudichak said losing 1,000 jobs in northeastern Pennsylvania or 500 jobs in Luzerne County would be devastating.

“That’s going to push unemployment up close to double digits. That’s unacceptable. We cannot survive that kind of hit,” he said.

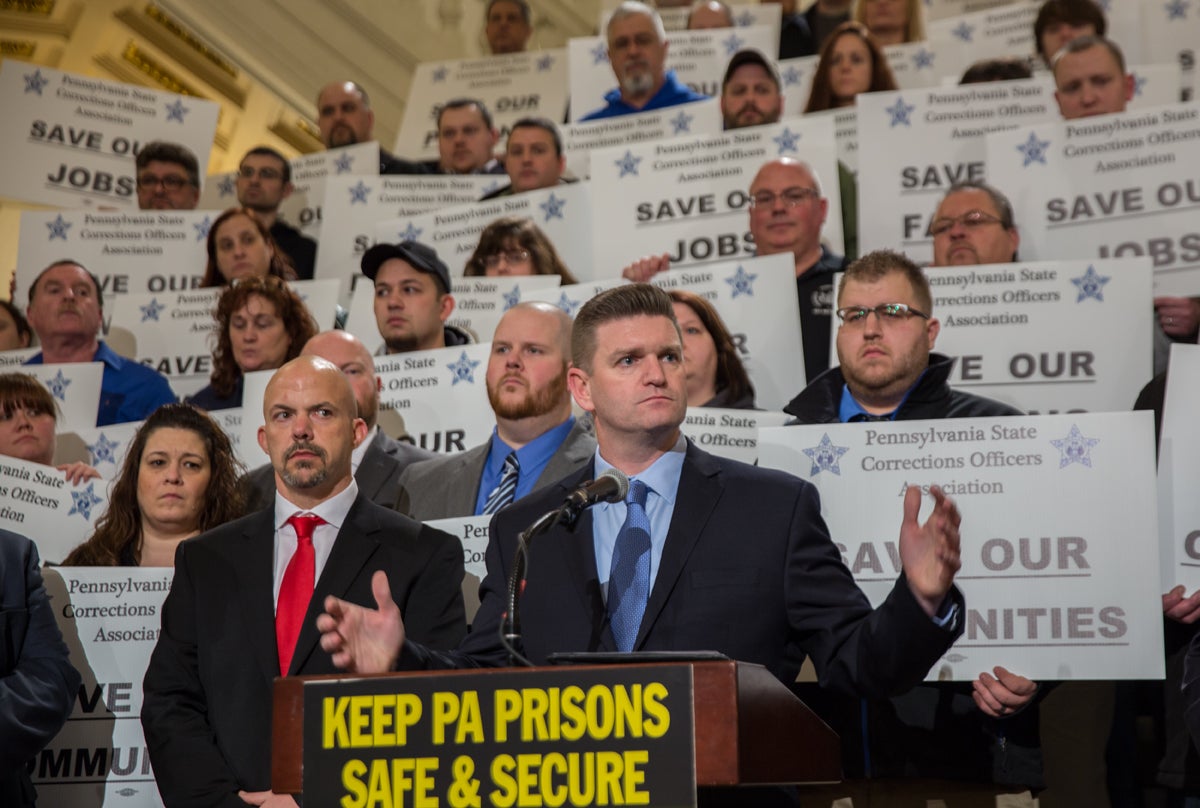

State Senator John T. Yudichak (D-Luzerne/Carbon) calls on Governor Tom Wolf to delay the decision to close two State Correctional Institutions at a rally at the Capitol in Harrisburg, Pa. on Jan. 23, 2017. (Lindsay Lazarski/WHYY)

State Senator John T. Yudichak (D-Luzerne/Carbon) calls on Governor Tom Wolf to delay the decision to close two State Correctional Institutions at a rally at the Capitol in Harrisburg, Pa. on Jan. 23, 2017. (Lindsay Lazarski/WHYY)

In Schuylkill County, the Frackville prison is the second-largest employer. Beyond possibly losing their corrections officers and their income tax, secondary businesses could be affected: from restaurants and gas stations, to real estate.

At a recent borough council meeting, real estate agent Helen Miernicki said just the rumors the prison might close affected her business.

“As a matter of fact,” she said, “I was out just a couple weeks ago showing a prospective employee housing and he decided not to buy, not knowing if he would have a job.”

Frackville has suffered a series of economic blows in the last 20 years. Mining work dried up, then manufacturing, the local mall will be auctioned off soon, due to a lack of tenants.

DOC hopes to find a new use for the closed prisons. The buildings are hard to sell, but if the federal government decided to house federal inmates at those prisons, money would continue to flow to nearby communities, said Wetzel.

Joel Dickson doesn’t think this is a binary choice. He’s the former superintendent of the Pittsburgh prison, which was mothballed in 2005 then reopened in 2007. The state could save money by downsizing the facility, rather than closing it, said Dickson. He added that closing a prison is hard on everyone.

“It was pretty traumatic across the board, for not only the staff, but the inmates, and families of the staff and the inmates.”

The Pittsburgh facility is one of a few prisons that offers inmates mental health and addiction programs, and also has a veterans unit. Dickson worries about disrupting those programs. Prisons don’t just lock people in their cells he said, they prepare inmates to re-enter society.

“Certainly the citizenry should be concerned about their tax dollars. But some tax dollars are well-spent. More than 90 percent of these folks are going to come back to live in your neighborhood.”

Ann Schwartzman is director of the reform organization, the Pennsylvania Prison Society. She said despite the Department of Corrections’ $2.6 billion budget, it is stretched thin, and can’t effectively provide the kinds of services inmates need. Her organization advocates assessing prisons to find out how to close more of them.

“We have a huge deficit. We can’t afford things that we need right now, such as working with our senior citizens, or helping with our infrastructure. We need those scarce dollars for real priorities. And incarcerating people that don’t need to be incarcerated or that need to be in treatment instead, just is a waste of our resources,” she said.

Wetzel says closing a prison is not something he and his staff take lightly. But the reality of the budget means they have to make tough choices.

Keystone Crossroads reporters Emily Previti and Eleanor Klibanoff contributed reporting.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.