Prenzlauer Berg: wild, wacky and wunderbar conflagration with a hippie-meets-hipster aesthetic

Twenty years down the line, and The Wall (“Die Mauer”) is everywhere. It’s there in the double line of cobblestones that runs through downtown Berlin, and it’s there in the vestiges that still stand in a few neighborhoods.

It’s even there — albeit increasingly less so — in the minds of many contemporary Berliners, who still correct themselves mid-sentence when they refer to “West Germany” or “East Berlin”.

It’s been a hard wall to tear down. But some day, it will indeed disappear. I heard it in the conversations I had with a few 20-somethings, just toddlers when the wall was finally toppled. “I never even saw the wall,” 24-year-old Nicole told me.

She discounts as “rumor” fears about what fate exactly awaited those who dared enter the so-called death strip: mines, vicious dogs, the like. Nicole’s not exactly practicing “ostalgie” (a neologism that suggests nostalgia for the “ost” —or “east” ). For her, the wall simply “didn’t impact my day-to-day life.”

It’s discomforting testimony — that being placed in a kind of mundane prison with precious little basics and certainly no extras ultimately became an acceptable norm. Dull and drab, but no big deal (unless, of course, you spoke out or tried to escape).

To its credit, the city itself is more than willing to face the Wall head on, as well as the assorted horrors of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) and its Stasi spy machine. There are a number of memorials, placards, exhibitions and tourist sites detailing its tortured history.

The Wall is most strongly felt, however, in its absence — its demolition has left a series of holes dotted throughout a city already devastated (and never fully recovered) from the heavy bombings it sustained during World War II.

The talk of the recovery of “poor but sexy” (in the words of its Mayor, Klaus Wowereit) Berlin left me ill-prepared for this still edgy appearance of much of the German capital. On the other hand, given that it’s had only two decades to basically rebuild itself, progress is noticeable, noteworthy . . . and proceeding at an ever-increasing pace.

In fact, much of the development in trendy East Berlin neighborhoods like Prenzlauer Berg, I was told, has occurred in the past decade or so. And, as one walking tour I joined convincingly put it, the city is ripe for a new brand: “creative sustainability.”

Dubbed so by Michael LaFond, the American expat who led the tour, this is basically the point where the creative economy and the green economy meet in a wild, wacky, and decidedly wunderbar conflagration that seems perfect for the hippie-meets-hipster aesthetic of Berlin.

It’s defunct breweries turned into performing arts destinations, it’s 21st-century adventure playgrounds, it’s vegan cafes and organic clothing boutiques.

Interesting, but nothing we haven’t seen before. A few stops on the tour, though, really grabbed my attention. And I’m not just talking about the building under which a group of enterprising, and desperate, Berliners once dug a tunnel to freedom.

The first example — just a block from a memorial to those who died while trying to escape to the West and from one of the city’s few extant guard towers — was a new church.

Built smack in the middle of the former death strip, out of ecologically-sound rammed earth, this “Chapel of Reconciliation” give pride of place to a steeple — a very poignant sort of garden ornament — that toppled from the 1894 church that stood on this site for almost one hundred years.

That church fell out of use once the Wall went up, and it was destroyed for security purposes by the GDR in 1985.

Ten years old now, the new church still hides an old bomb (discernible through a panel cut into the floor) that was discovered during the rebuilding, and its weed-strewn front yard is currently a construction sight for an expansion of the nearby Wall memorial.

Our tour continued through patchy developments of new car-free housing and passive energy co-ops mixed with Soviet-era apartment blocks and still-empty lots.

On Oderbergerstrasse, LaFond indicated a variety of planters that sat outside the beatnik stores. Made of cheap cinderblock, rough-hewn wood, and rusted iron, they are the neighbors’ answer to a planned redevelopment by city officials.

Residents, fearing an over-prettifying of this graffiti-heavy area that’s been a center of counterculture and squatters homes since the 1960s, took matters into their own hands, tidying up in a crafty (in both senses) way.

As we walked through the neighborhood, LaFond pointed out freshly-painted stucco on one lovely building after another, saying that little by little the area was being scrubbed and spit-shined. We turned onto one particularly successful street, Kastanienallee, nicknamed “Casting Alley” because of its sudden onslaught of beautiful people.

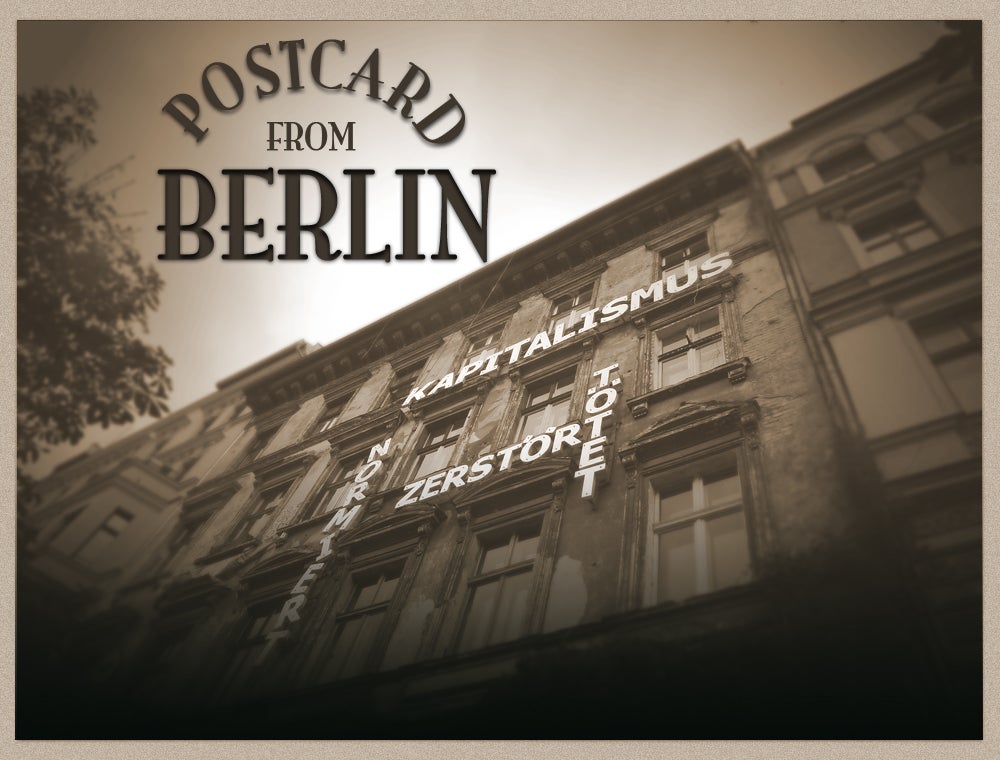

One legendary holdout here: a majestic building covered in rampant weeds, scrawled graffiti, and tattered flyers. Running downs its facade are large block letters that say in German: Capitalism Kills, Destroys, and Normalizes. “The whole area was filled with buildings like this even just 10 years ago,” LaFond observed.

Joining me on the tour were a handful of architects, planners, and sustainability types who had been invited to tour Germany courtesy of an exchange program. In a small world coincidence, one was architect Jose Castillo who, it turns out, teaches a studio at Penn, to which he commutes every other week from his home in Mexico.

Castillo’s specialty is an emerging field called “informal urbanism,” which includes the study of squatters and other gentrification-resistors such as tent cities.

We continued on, past bike parking and lanes galore, past stroller gridlock and farmers’ markets, and past a tiny food cooperative that’s trying to hold its own against the giant LPG Blomarkt, Europe’s largest organic supermarket.

Near the end of the tour, we reached FIT, my favorite stop, both for its dogged quirkiness and for its high photo-worthiness.

FIT — that stands for the German translation of First International Filling Station — marks the debut of what’s become a quest by artist Dida Zende to repurpose abandoned gas stations as centers of creativity. Based on the “social sculpture” ideas of Joseph Beuys, they also encourage folks to think about what Zende calls “this gas craziness.”

Zende has staged everything from film festivals to informal soccer-watching parties here, and has since done the same in Copenhagen, Bregenz (Austria), and Miami. In general, his friendly takeovers act as temporary projects before the stations are slated for demolition. Berlin’s tiny red-and-white example, however, is a culturally-protected structure. Erected in 1926, it represents one of the first buildings to offer covered shelter for automobiles.

In its entrepreneurial ingenuity, its green bonafides, and its quixotic originality, this charming effort was a perfect, er, FIT for LaFond’s take on the ways in which this still-emerging city will define itself.

Compared with the redone Potsdamerplatz, where many of Berlin’s tourist attractions are located, this look at the places where the seedy and the sublime intersect proved inspiring and thought-provoking.

Potsdamerplatz may indeed be a miracle — it’s a patch of city center that’s been rebuilt literally from nothing: just one building in the area is pre-WWII. But it looks like any such new development anywhere, even with its green roofs and its energy-efficient windows. It’s a vision of someone else’s future.

Prenzlauer Berg, though, is a very Berliner future.

Contact JoAnn Greco at www.joanngreco.com

Check out her new online magazine, TheCityTraveler at www.thecitytraveler.com

Previous postcards: Atlanta, Kansas City, Paris, Detroit Part 1, Austin, China, San Francisco, Germany, Pittsburgh, New Orleans,New York City, Boston, San Antonio, Minneapolis, Detroit Part 2, Templehof, Chicago, Italy, St. Louis, Houston.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.