Postcard from London: No car? No problem!

March 29, 2010

By Jeffrey Barg

For PlanPhilly

At the red light on Broad Street, half a dozen bicyclists were stopped, waiting for the green.

Which is your first sign that this isn’t Broad Street in Philadelphia.

Rather, it’s the corner of Broad Street and Parks Road in Oxford, England, a country better known for the London Underground than for its thriving bike culture. But thanks in part to London’s decision to implement congestion pricing for cars in the city, biking has exploded in the country, with gorgeously separated road space that would make bikers on Spruce and Pine Street pine away for better, safer conditions. At the aforementioned Broad and Parks intersection, one renegade biker broke from the pack and rolled through the red light, prompting an older British gentleman, also on a bike, to shout, “Why don’t you follow the laws of the road like the rest of us?”

Definitely not Philadelphia.

Congestion pricing removed cars from the roads, which freed up space for more bike lanes. Green-painted two-way bike lanes are separated from car traffic by physical buffers, raised up from the road a few inches, although it’s probably in some cockamamie number of centimeters that we Americans just can’t understand since it’s the metric system.

A London bike lane

Signs point the way for bike-friendly routes around the city. What’s the best way to get to the King’s Cross Underground station on a bike? Just look up and the signs will tell you.

The signs aren’t just for cyclists

An example of the signs geared toward non-drivers.

Additionally, signage has popped up all around downtown London to make wayfinding astonishingly easy for cyclists, pedestrians and transit riders.

London’s not the world’s most complicated city, but it ain’t a grid either. Streets change names at intersections, and a particular road name might have 10 different incarnations: Radnor Avenue, Radnor Road, Radnor Street, Radnor Walk, Radnor Gardens, Radnor Lodge—all in entirely different parts of town. The new maps and signs, called Legible London (http://www.tfl.gov.uk/microsites/legible-london/), are oriented with the top indicating straight ahead (instead of top north), like Center City’s navigational signs. Unlike Center City’s, though, they include 3-D drawings of buildings that help pedestrians find their bearings, indicate building entrances and multi-level walkways, sprout up from the ground (instead of being hung high on a signpost) for easy reading, and feature maps at bus stops to help transit passengers continue their journeys on foot.

And that’s not all you’ll find at bus stops.

Quite unlike anything SEPTA provides, bus stops include maps of where bus routes are going, where they stop, and machine kiosks to buy bus tickets.

Drool.

London Transport Museum

All of this points to a country clearly, passionately in love with its public transit.

(The newly opened London Transport Museum—isn’t it cute how they call it “transport”?—is a wonder. I spent three hours there.) And for a land with that much transportation love, Lord Adonis, the secretary of state for transport, just plopped a big, sloppy wet one on the city. While we were there, he presented the government’s report on HS2, a proposed new high-speed train to travel between London and the West Midlands. They’re looking for the line to transform the country.

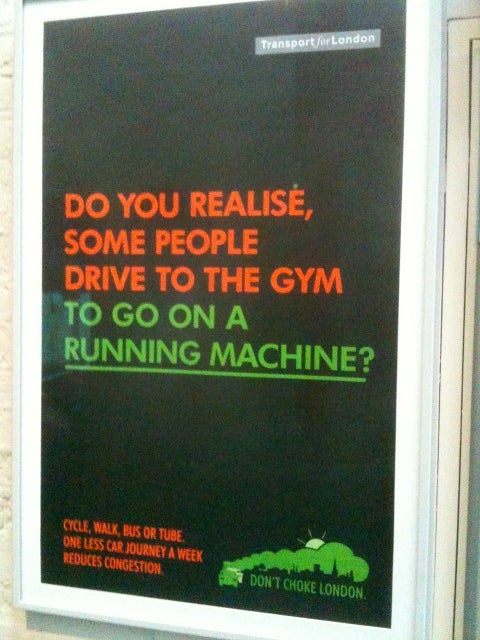

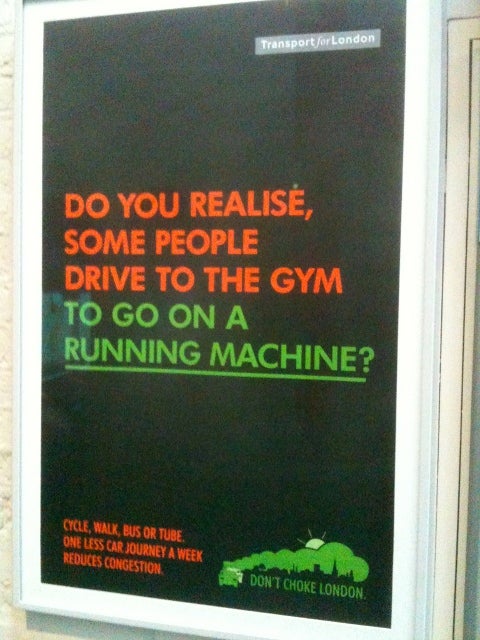

A poster encourages Londoners to leave their cars behind.

Could such trains work here?

I was there with a studio team of second-year PennPlanning students to look at the striking parallels between the proposed HS2 and the U.S. Northeast Corridor, where we’re trying to make the argument for a high-speed rail (HSR) system of our own. Obama recently dropped $8 billion for HSR in the States, but the lion’s share went to California—and ours is just a fraction of what would be needed to build a network here like they already have over there, to say nothing of high-speed trains already existing elsewhere in mainland Europe, Japan and China.

The similarities between the English HSR route and our Northeast Corridor are striking. Taken as a whole, population along the Northeast Corridor: 49.6 million. U.K. population: 51.1. Both lines are about the same length. The Northeast Corridor has a GDP of about $2.59 trillion; the U.K., $2.29 trillion. And yet travel time from Washington, D.C., to Boston is north of six hours, while London to Glasgow is closer to two.

Whether or not Philadelphia would benefit from high-speed rail is an open question. In the U.K. analogy, Philly is the Manchester to New York’s London. Would a 35-minute connection between Philly and New York benefit both cities, allowing the pair to take advantage of each other’s job markets, cultural offerings and neighborhood amenities? Or would such a link allow New York to hoover up, as the Brits like to say, whatever good jobs are left in Philadelphia? Given the opportunity to choose from both the New York and Philly labor pools, would firms choose to set up shop in the bigger, more international metropolis?

Tough to say. But in the search for answers, all eyes are across the pond.

Jeffrey Barg is a second-year student in Penn’s Department of City and Regional Planning. He can be reached at jeffreybarg@gmail.com

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.