Make room for cartoons among America’s founding documents

Did political cartoons contribute to American nation-building? This exhibition at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania shows how.

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

Political cartooning and the United States of America came up together. A new exhibition at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania suggests the two are inextricably linked.

“Cartoons as Political Speech in Colonial and Contemporary America” features political cartooning from 1764 to today, depicting how satirical drawings defined our American identity and became a tool of nation-building.

“Our founding story is one of feeling oppressed by a foreign power, or a power that’s thousands of miles away, feeling that we don’t have a voice at the center of power,” said David Brigham, CEO of the Historical Society. “That story heats up in the 1760s.”

Before the 1760s, American colonists rarely used cartoons to express political opinions. However, as the desire for independence grew in the colonies, cartooning became a popular medium for political expression.

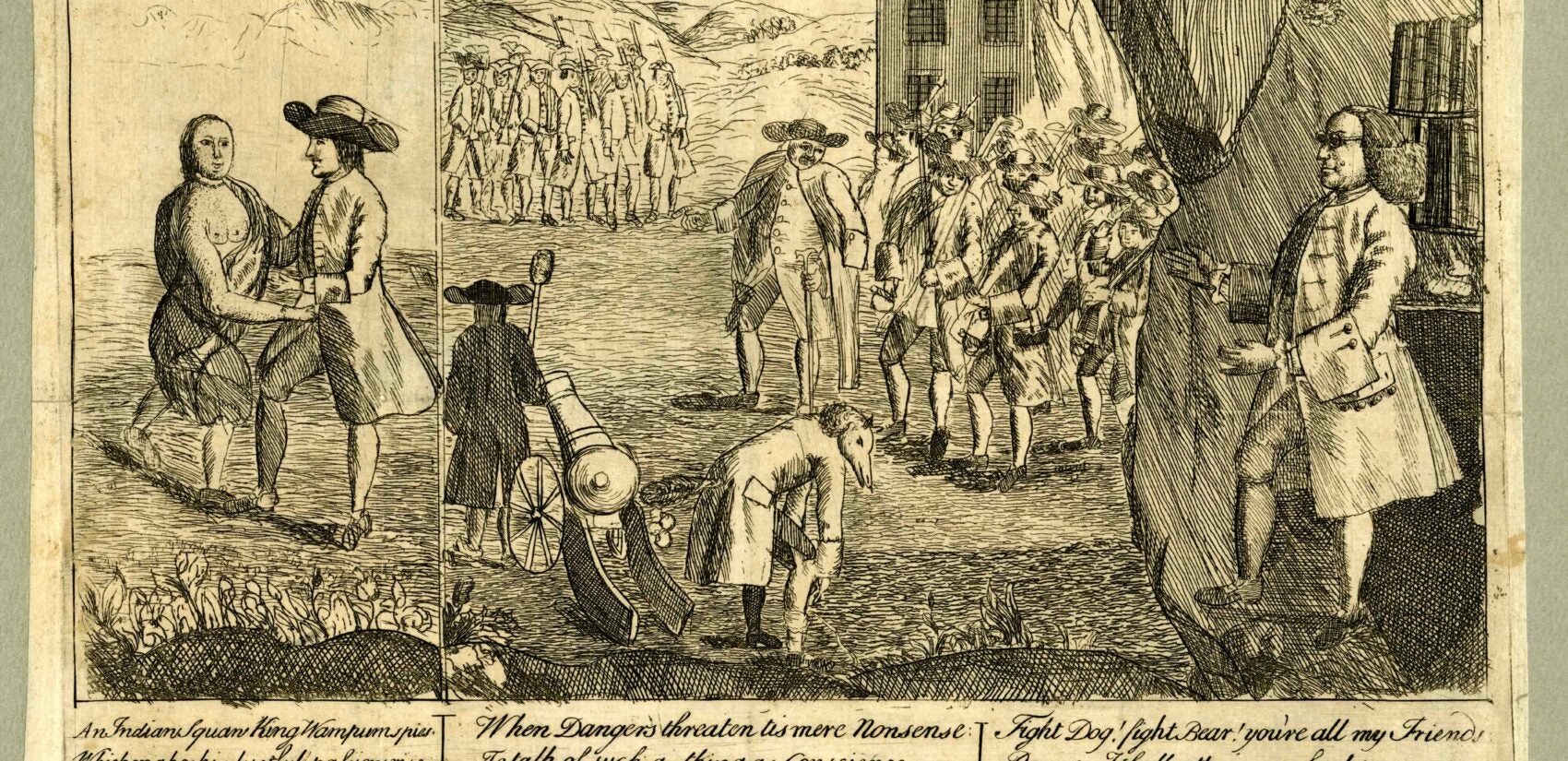

“Cartoons as Political Speech” starts with 1764 cartoons about the Paxton Boys, a Pennsylvania vigilante group who instigated a series of attacks on Indigenous people because they felt the Pennsylvania colony was insufficiently secured. They ultimately marched, unsuccessfully, on Philadelphia where Quaker leaders shielded Indigenous people.

The Paxton Boys incident became a flash point leading to reams of pamphlets, articles, songs and cartoons targeting the colony’s Quaker-led legislature, which denied defense funding in the outer regions of Pennsylvania. The cartoon on display at HSP accuses Benjamin Franklin of leveraging the Paxton incident to amass his own political power, “For I can never be content/ ‘Till I have got the government.”

Brigham said it is the nature of cartoons to go after figures of power.

“The perspective of the underdog, the repressed or the oppressed, that’s generally the point of view,” he said. “The people in authority are the people who are the targets of the cartoons, which tend to be caricatures.”

When the British parliament passed the Stamp Act a year later, imposing a new tax on colonists to pay for the King’s troops stationed there, cartoonists drew a new target.

Cartoonists in the American colonies found allies in England, where both groups created cartoons mocking members of British parliament. “Cartoons as Political Speech” features a case of cartoons from London lampooning figures like Prime Minister George Grenville, who ushered in the Stamp Act, and Lord North, prime minister during the Revolutionary War.

In a 1766 cartoon of a funeral procession for the Stamp Act, the artist Benjamin Wilson sketched a street dog urinating on the leg of political writer James Scott.

“They are very pro-American in their point of view,” Brigham said. “Relatively little commentary on the King. The seat of power is with the prime minister. That’s where the cartoons take their aim.”

British and American cartoonists spent about a decade pillorying English politicians. But 1775 saw the end of that honeymoon.

“In 1775, after the British standing army aims its guns at the colonists at Lexington and Concord, the Continental Congress passes a resolution that says the American colonies have the right to take up arms,” Brigham explained. “That’s the first time that the cartoonist in London turns against the Americans, because that’s seen as an insurrection.”

“Cartoons as Political Speech” comes up-to-date with editorial cartoons by Signe Wilkinson, the longtime Philadelphia Daily News and Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist who now draws a weekly item for the Philadelphia Inquirer.

Wilkinson explores a broad range of work, including women’s rights, public schools, trash and public safety. One of her bedrock issues is freedom of speech, which ties her illustrations back to the original cartoons from the birth of the nation.

“These are founding principles and equality and censorship,” Wilkinson said. “I like to use the Founding Fathers as a place to get started.”

“I have been the beneficiary of working at a newspaper, The Daily News, for most of my career, where there were so many different points of view. So much of it was expressed in the paper that it was full of free speech,” she said. “But you can see where, you know, school boards want to cut down on what people say, municipalities want to limit speech. So I feel it’s the bedrock of keeping our democracy going. That’s why I do cartoons about it.”

“Cartoons as Political Speech” puts Wilkinson in the context of her opinionating forebears from 260 years ago. They share much in common: concern about taxes, disdain for pretentious authority and keeping tabs on who gets a voice in the seat of power.

There are also differences. Contemporary artists like Wilkinson tend to make simple drawings that can be interpreted instantly, while the densely composed cartoons of the 18th century hold layers of symbolism and literary metaphor within their depictions.

“I need to really unpack them,” said Brigham, a trained historian specializing in 18th and 19th century American and British history. “It takes hours to figure out who all the people are and what their point of view is.”

Wilkinson said cartoons then and now are different because media is different. As a daily newspaper cartoonist previously, she had to immediately respond to the news cycle in real time. Back in the day, cartoons were published weeks or months after a particular incident. They were expected to tell a more complete narrative in a single image.

“They chronicle a lot, rather than a little,” she said. “It is a very different way of looking at the world.”

“Cartoons as Political Speech” will be on view at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania until Aug. 2.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.