Police culture, and what the Chauvin murder verdict might signal for the future

Officers testified against their colleague and helped convict him in George Floyd’s death. Was it a sea change, or just one high-profile prosecution?

Police officers keep a watchful eye as peaceful protesters march down Flatbush Avenue on Tuesday, April 20, 2021, in the Brooklyn borough of New York. (AP Photo/Brittainy Newman)

Derek Chauvin’s conviction on murder charges in the Minneapolis police killing of George Floyd was rare, both in terms of the outcome of the trial and what led up to the verdict.

There have been countless cases over the years of law enforcement killing people on camera, and a vast majority of officers have walked away scot-free, despite the very visible blood on their hands. The difference in this case, however, was that the prosecution presented plenty of testimony from law enforcement officials, including Chauvin’s former police colleagues.

David Fisher is a retired Philadelphia police detective and president of the National Black Police Association, Greater Philadelphia Chapter. He is optimistic about the outlook for future cases.

“What it means going forward is that I believe that more police officers will now step up to the plate and give honest opinions, give honest testimony, turn in more police officers who they may feel have done things incorrectly in terms of violating someone’s rights or not having accurate probable cause for arrest,” Fisher said.

Since last week’s verdict, many have speculated that the so-called Blue Wall of Silence — an informal code among police officers that keeps them from speaking up when they witness brutality, misconduct, and corruption in their ranks — is showing signs of decay. Others say the trial’s outcome begs still larger questions: Did the Blue Wall merely bend under the weight of the evidence against Chauvin? Is this much maligned aspect of police culture truly behind us?

“I call total BS on those statements,” said Kayla Preito-Hodge, an assistant professor of criminal justice at Rutgers University-Camden, who studies the intersection of race and policing.

As someone who looks at the big picture of sociology and criminology, Preito-Hodge believes that the officers’ testimony in Minneapolis was just a strategic move to push the false narrative of Chauvin’s being the “bad apple” rather than a symptom of larger organizational failure and an us-versus-them police culture.

For Hans Menos, vice president of law enforcement initiatives at the Center for Policing Equity, the Chauvin case was “low-hanging fruit” for police departments to criticize.

Ultimately, said Menos — who previously led Philadelphia’s Police Advisory Commission — it was an “outlier event” and not a sign of things to come.

“We need to see, in Philadelphia and around the country, police officers standing up to things that aren’t recorded [for] nine minutes and don’t lead to national outrage, just standing up for what’s right, because they’re the one witness … and they can make a real difference. I don’t think we’re seeing that,” Menos said.

Preito-Hodge said the unexpected police testimony was a way to preserve and legitimize a system that has rightfully come under fire in recent years.

“Derek Chauvin was the sacrificial lamb for blue culture and for police departments across the country,” said Preito-Hodge.

Police culture’s many sides

The Blue Wall of Silence is far from a myth. In the 2015 police shooting of Samuel Dubose, a University of Cincinnati officer corroborated false accounts. In 2012 in Baltimore, a detective reportedly faced retribution and intimidation from fellow officers for speaking up about police misconduct. Cases such as those served as context for University of Chicago researchers who looked into possible solutions.

Another aspect of “blue culture,” however, is the philosophy known as the “Thin Blue Line,” the concept that police stand between society and violent chaos. It has become a prominent symbol in Blue Lives Matter flags and insignia.

In 2020, The Marshall Project, an online journalism nonprofit that focuses on criminal justice issues, examined the history of the Thin Blue Line and found that it can foster an us-versus-them mentality in police departments. The Thin Blue Line flag, a black and white American flag with a single blue stripe, has been flown by white supremacists at their rallies.

Philadelphia Police Commissioner Danielle Outlaw’s office said she was not available for an interview for this article. Other top regional police officials interviewed over the past week didn’t deny that the two philosophies coexist, but they also said they don’t believe those aspects of police culture are present in their departments.

Like big cities such as Minneapolis and Philadelphia, inner-ring suburban communities have been the setting of high-profile police killings of Black people in the United States, such as the fatal April 11 shooting of Daunte Wright in Brooklyn Center, Minnesota, a suburb of Minneapolis, and the 2014 shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, a suburb of St. Louis.

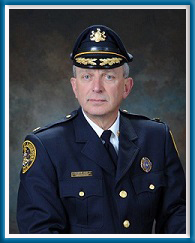

John Viola is chief of police in Haverford Township. Just outside the city in Delaware County, with about 49,000 residents, the township is more than twice the size of Ferguson.

“That police culture — there’s no secret, it’s been there for years, but it is changing. It really is,” Viola said. “Here at Haverford, after the George Floyd verdict, we enacted a new ordinance for duty to intervene and act, so our officers are required to jump in if they see another officer doing something wrong.”

According to a Philadelphia Police spokesperson, the city’s department currently has a policy in place to do the exact same thing. But in practice, Menos said, that simply has not been the case.

“So in Philly, officers who speak up for any reason learn immediately that that’s not OK. They get shunned, their supervisors directly or tangentially threaten them. Their fellow officers do the same. So speaking up … in the culture of the Philadelphia Police Department, can be detrimental to your career,” Menos said.

Mark Talbot is chief of police in Norristown, the 34,000-resident county seat of Montgomery County — a population not much bigger than that of Brooklyn Center, Minnesota. He said he felt relieved on hearing the Chauvin guilty verdict, but believes there is still a way to go.

“It doesn’t feel like anything close to the reforms that need to happen,” Talbot said, “but it doesn’t represent a setback, as so many events lately have seemed to represent.”

Talbot said it would be disingenuous of him to deny the existence of “dysfunctional” police culture that leads to police misconduct, although he added that not everyone buys into it and it can mean different things in different places.

“Dysfunctional police culture is reflective of something. And that something that it is reflective of isn’t necessarily inconsistent with the strands of problems in [American] culture,” Talbot said. “We’ve got to untangle those two things: the parts of our culture outside of policing that are not fair and are not consistent with justice and fairness and the parts of policing that are connected with those broader strands that tie everything together in a knot of dysfunction.”

Although some of the police chiefs interviewed for this article were defensive regarding police culture and antagonistic toward some of the proposed systemic solutions to ending police violence, like defunding the police, many of them agreed with the sentiment that police are being called to address situations where they have no business being.

“I think that we’ve got to pay attention to all of the routine things that we do that are coercive that feel like a foot on the proverbial neck of people who are vulnerable. From towing cars, to making demands, to giving out citations, to arresting, to using our tasers, we’ve got to look at all those things — and eliminate every instance that’s not the best idea at the time,” Talbot said.

“And it’s not just deadly force. If all we’re paying attention to is use of deadly force, we lose, because it’s so much more than that.” he said. “What people are desperate for is to interact with police departments and feel like they are full citizens of the United States of America that matter as much as anybody else matters. And the way that you interact with somebody communicates that very clearly.”

In Bensalem, with a population of about 55,000 just over the Northeast Philadelphia border in Bucks County, Director of Public Safety Fred Harran took a less systemic view of the Chauvin verdict and police culture. While acknowledging that “things have to be fixed if they’re broken,” he said he believes that the issues in policing are due to “bad apples.”

With regard to possible solutions to police brutality, Harran balked at the idea of defunding or abolishing the police.

“If you start that trend of defunding, you’re going to have more abuse. Unless you’re going to just end law enforcement and just make it like the movie, ‘The Purge,’ that’s not gonna happen, ending law enforcement. So … for all the listeners, get that out of their heads. And if they do end it, God help us all,” Harran said.

Pursuing change

After waves of protests erupted across the nation shortly after the murder of George Floyd last year, many of the region’s municipalities and police departments announced numerous initiatives in an attempt to reform the system.

The Police Chiefs Association of Montgomery County took a deep dive into the incident and decided to put out a statement condemning Chauvin’s actions, said Michael McGrath, police superintendent in Lower Merion Township. The county, which has a long border with Philadelphia, has about 830,000 people and is roughly the same size as Columbus, Ohio, where 16-year-old Ma’Khia Bryant was fatally shot by an officer earlier this month.

Feeling as if justice was served by the Chauvin verdict, McGrath said he was happy with the result of the trial and satisfied with the way the Minneapolis Police Department stepped up to strengthen the case of the prosecution.

“I was pleased to see particularly the chief of police show that he was taking his leadership seriously, and stepped up and made comments that I think many law enforcement leaders around the country would have said as well,” McGrath said.

After Floyd’s death, Delaware County formed a criminal justice task force led by District Attorney Jack Stollsteimer.

“We have a great group of police leadership and community leadership here in Delaware County, and with the support of our County Council members, we all collectively got together and held a series of meetings and discussions in working groups, where we talked frankly, about the issues that are confronting policing in America today, and particularly how it affects us us here in Delaware County,” Stollsteimer said.

Upper Darby — Delaware County’s largest town and the most populous of Philadelphia’s collar-county suburbs, with more than 80,000 people — has made several changes to its police department under the leadership of Superintendent Tim Bernhardt. The police force is getting body cameras, and it has made efforts to demilitarize and diversify its members.

“I got rid of SWAT. SWAT had a lot of negative interpretations attached to it over the years. I mean, you can go back to the ’70s and ’80s and even probably further than that to the ’60s … so there’s no longer SWAT here. What we have is an emergency service unit,” Bernhardt said.

He was also involved with a countywide initiative to decriminalize marijuana, which Bernhardt said he took a lot of flak for in an area that was formerly a Republican stronghold.

“Instead of locking them up, putting them through the system, having a criminal record, having to pay for an attorney, losing their driver’s license, maybe not being able to get a job, maybe not being able to get into college — at least that’s just one more step that we were able to implement here in Upper Darby, just again, to improve how we interact with our community,” Bernhardt said.

After seeing criticism on social media about the way police handle mental health situations, Bensalem’s Harran began a co-responders program, where social workers are embedded with police officers to help them handle mental health calls and to follow up with people in need of services.

“We were able to obtain pilot funding for two years for this, to see if it’s going to work or not. And they have been hired since November of 2020. And they’ve been so successful so far,” Harran said.

Still, for residents of the Philadelphia region most affected by issues of racial justice and racist policing, the overarching question was and remains: Were these initiatives and announcements just lip service, or did they actually have an impact?

Discussions with various officials across Philadelphia’s suburbs did not yield much in terms of quantifiable measures of success.

Viola, of Haverford Township, did offer up his department’s use-of-force statistics.

Over the course of three years, Haverford police officers have only drawn their weapons twice. However, that doesn’t mean the department was free from controversy. In 2020, Haverford officers were caught on video striking a handcuffed individual with a baton. The officers were cleared of wrongdoing.

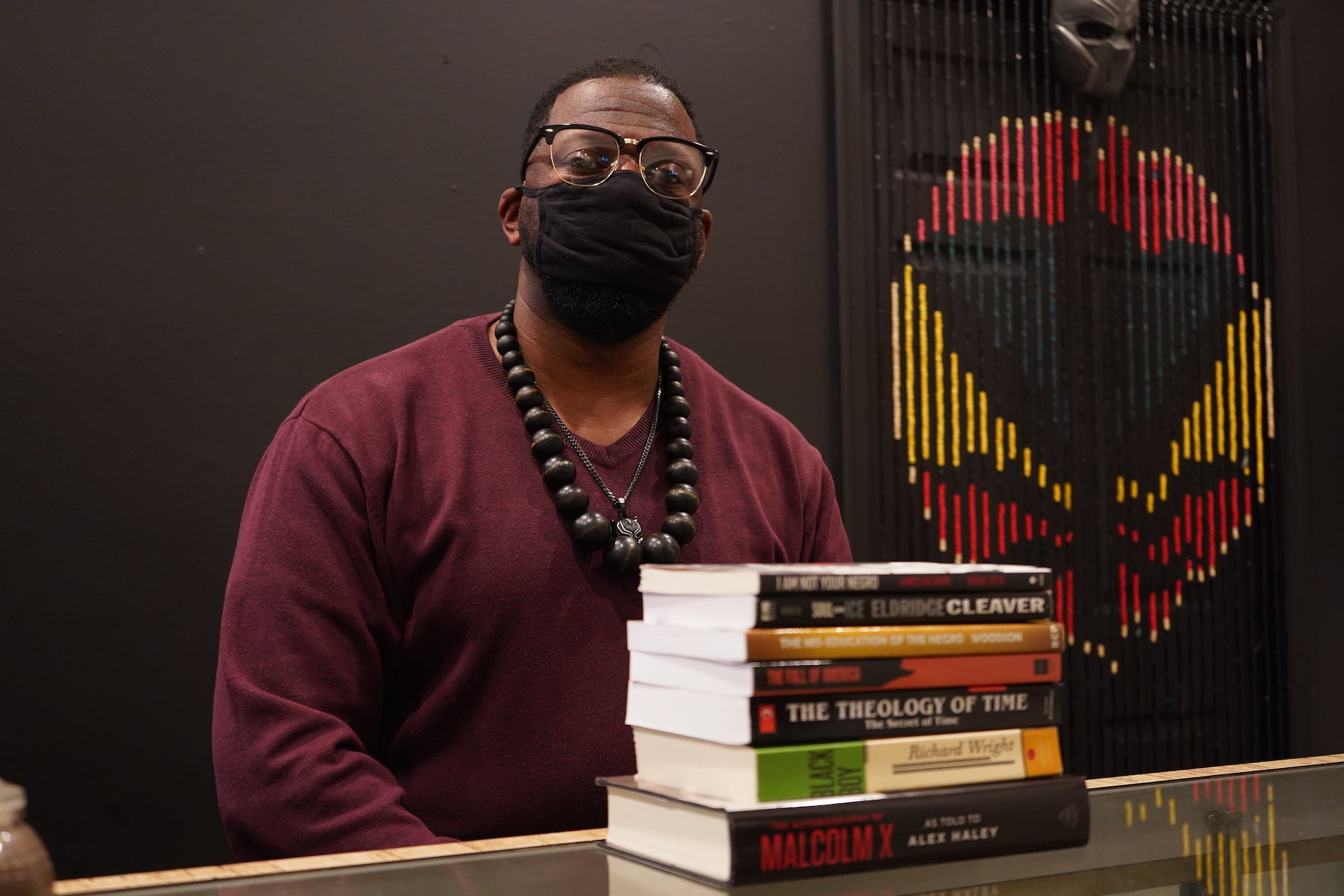

Community leaders have had varied levels of success reaching out to police departments. The NAACP Ambler Branch got all 10 of the Montgomery County police departments in its district to sign on to a memorandum of understanding. Shaykh Anwar Muhammad, NAACP Ambler Branch president, said it took months of relationship-building to get that done.

The community outreach engagement plan the effort produced seeks to reduce bias in policing, increase transparency, and strengthen community-police relationships. Though Muhammad is proud of the initiative, he has serious questions about results.

“When are we going to get to see, like tangible, tangible proof that these things are working?” Muhammad asked.

Reaction from community members and activists to many of the reforms has been lukewarm. While they commended the decriminalization of marijuana and reevaluation of the policing of mental health, they feel as if they have been left out of the conversation.

Carol Kazeem is an organizer with Delco Resists, which fights for social justice in the region. Though her group has had conversations with a few individuals from municipal and county departments within Delaware County’s criminal justice system, she said they have yet to have a seat at the table with the county’s “system” and leadership regarding reforms.

“It does not seem like we have been able to bridge that gap yet. I don’t know if it’s the barriers within our government. I don’t know if it’s our system. But I do believe that in order for us to [bridge] that gap amongst everyone, officials, officers in the community, we all have to sit down on one accord on a collective effort,” Kazeem said.

As a Black woman, Kazeem said, she has been in situations where she felt disrespected and harassed by police.

“This is nothing new. But I do hope with everything that has been transpiring … I really do hope that people now understand that this is a serious matter,” she said.

Was it justice?

Soon after the Chauvin guilty verdict last week, there were many takes on social media that sought to determine whether what the world watched unfold during the trial was justice or simply accountability.

As director of Delaware County’s Public Defender’s Office, Chris Welsh said he is a believer in the jury-trial system. He said he feels as if justice was served.

“For my entire career, starting as a public defender in 2005, stories of this type of conduct I’ve heard all the time from my clients and from the communities where my clients generally come from … but now with cellphone videos, you can’t really dispute it,” Welsh said.

For Preito-Hodge of Rutgers-Camden, Chauvin’s conviction was a step in the right direction, but neither accountability nor justice.

“I do believe that justice and accountability are proactive things as opposed to reactive things. So proactive in that … Black people shouldn’t have to worry about going out and being killed by the police,” Preito-Hodge said.

Citing the New York City police killing of Eric Garner, she pointed to the almost daily occurrence of police violence. And while most officers aren’t convicted, the few that are also leniently punished, Preito-Hodge said.

In cases such as the Dallas police killing of Botham Jean by off-duty officer Amber Guyger in Jean’s own apartment, the officer was convicted of murder only to be sentenced to 10 years in prison.

With that in mind, Preito-Hodge said, she hopes Americans keep up the momentum in demanding change.

“I do hope that the American people not only put one particular officer, one ‘bad apple’ on trial, but also put the rest of the police force on trial.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.