Photos show the other side of Thomas Eakins

ListenOne of the best American painters of the 19th century, Thomas Eakins, was an early adopter of photographic technology. It turned out to be professional suicide.

Thomas Eakins was 35 years old in 1879 when he was hired by the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia to teach drawing and painting. He had already painted his masterpiece, “The Gross Clinic,” a dramatic tableau of a 19th century surgical operating theater at Jefferson Hospital, as well as bucolic images of rowers on the Schuylkill River. He is recognized as one of the finest figurative artists in America.

Almost immediately afterward, in 1880, he bought his first camera and got the bug.

“Eventually, he began to integrate it into his teaching methods, and his own production of art,” said curator Susan Danly. “Many photos in the collection seem to have filled the spot in his artistic production that would have been done by sketches and drawings. He relied on the camera instead of drawing.”

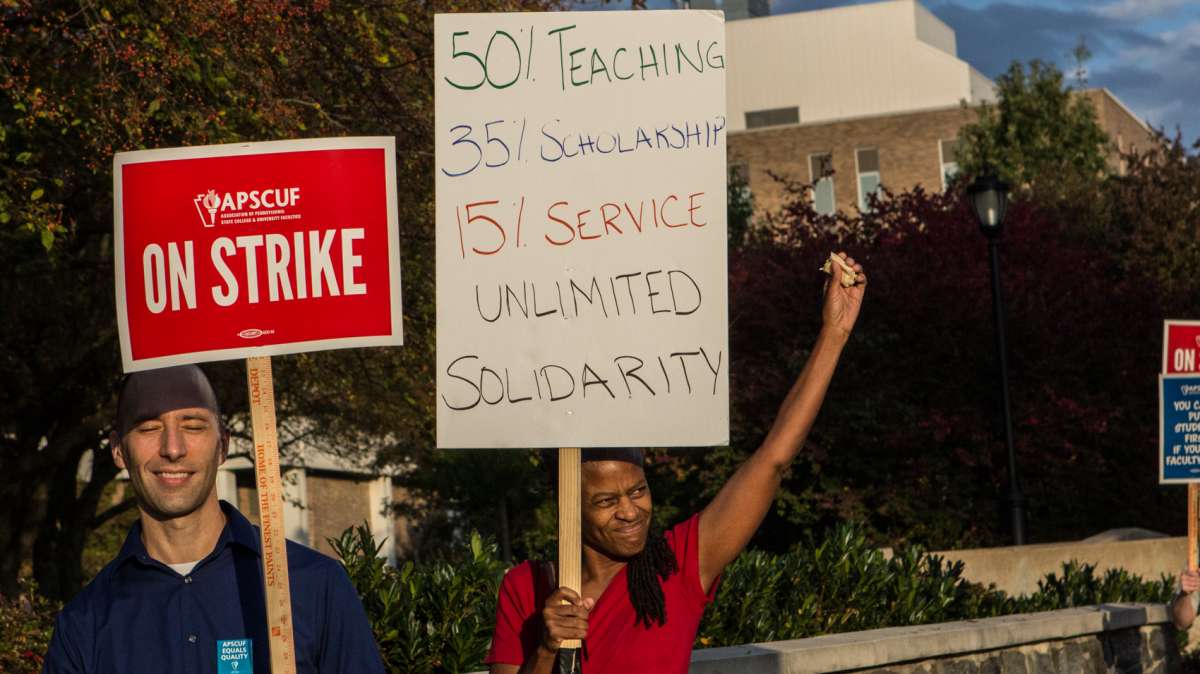

Danly, with co-curator Anna Marley, put together “Thomas Eakins: Photographer” at PAFA, an institution which had fired Eakins in 1886, in part because of his photography. Eakins strongly believed art students should learn figure drawing from nude models, an idea that was radical at the time, particularly for female students. It was too radical for the Academy at the time.

He was forced to resign. Many of his closest students quit in protest.

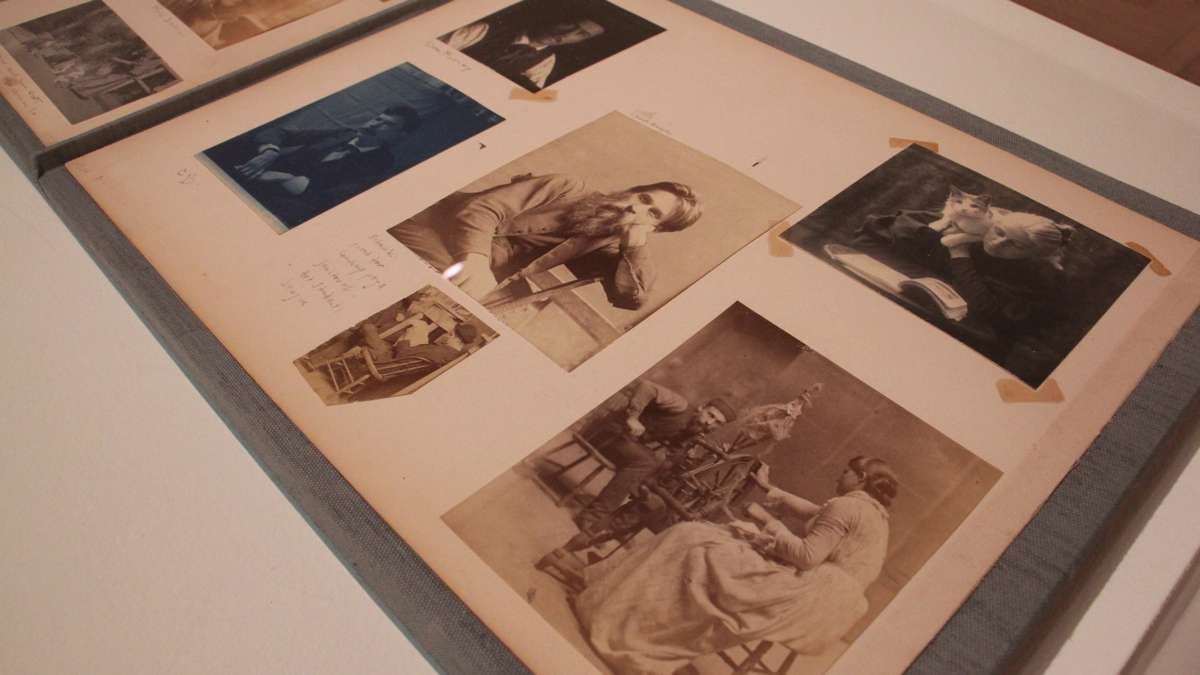

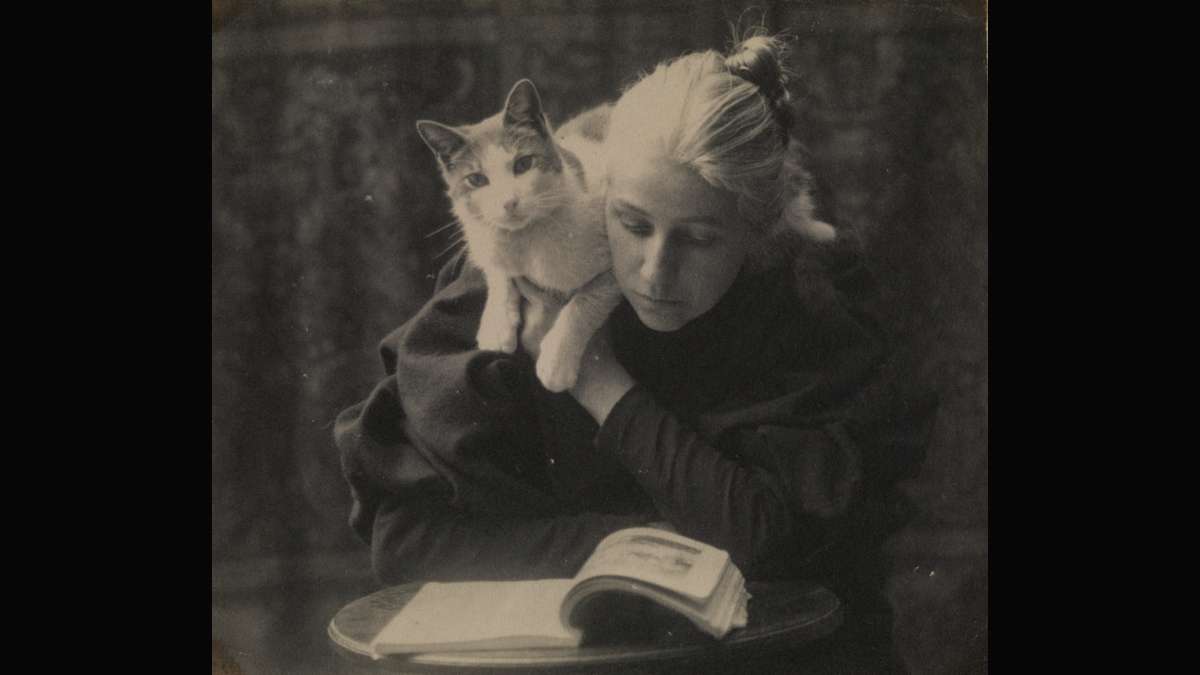

PAFA has the largest collection of Eakins photos — 650 images he took over 25 years. A majority of them are nudes. Danly says they were originally aides for painting, not to be exhibited or shared. But sometimes the nude subjects were his own students, and sometimes he would appear nude in the photos with them.

“These are not public photos. They were private. He thought it was nobody’s business what he did,” said Danly “He knew it was in the aid of art, that it was not pornography. They are certainly not pornographic in any way. But they are troubling.”

Eakins would photograph nudes in artful poses, and sometimes in very plain standing positions as though they were anatomical data. Many photographs protect the identify of nude women by masking their faces with tied kerchiefs. From the perspective of 2016, these look particularly disturbing as they echo the prison abuse photos from Abu Ghraib in Iraq.

PAFA, which has always been both a teaching institution and a museum, still has a strong curriculum of classical figurative training, using Eakin’s approach to life drawing. But even by today’s more liberal arts training standards, director David Brigham says no school would allow a teacher to ask his students to pose nude or be nude with them. “He would not be employable,” he admitted.

Nevertheless, PAFA has been proactively burying the hatchet with the Eakins (who died in 1916). The exhibition of 60 photographs and related objects was made to mark the centenary of his death, along with exhibitions by contemporary artists reacting to Eakins.

Eakins never exhibited his photos as art, as they are in this exhibition, and scholars did not know they existed until 1985. They had been in the possession of one of his students, Charles Bregler, who rescued thousands of items from the dustbin after Eakins died. The collection was passed down to Bregler’s descendant who held onto it tightly, still holding a grudge against PAFA’s treatment of Eakins.

PAFA’s curator at the time Kathleen Foster, gently coaxed the collection away from the Bregler family (for a handsome price). Once it came to light, the collection changed the way scholars viewed Eakins.

“It gave us a much better picture of what the camera meant in his art production, and his personal life,” said Danly, who was part of the team that archived the collection. She would eventually write a book about it, “Eakins and the Photograph” (1994).

The exhibition also includes many candid, domestic images, like pictures of Eakins friends, family, his wife Susan, his Irish setter Harry, and his horse Billy. He even took a picture of his wife with his horse, both nude.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.