As Philly teacher contract talks drag on, superintendent keeps tough stance on work rules

Listen

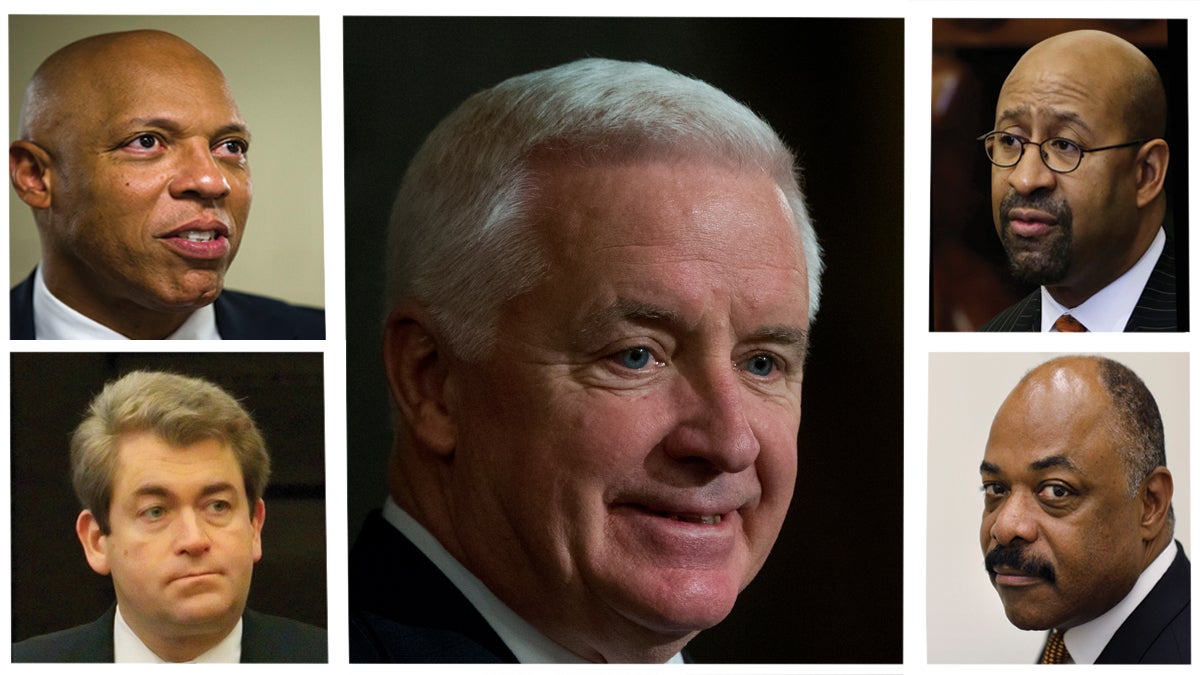

(Clockwise) Philadelphia school district superintendent William Hite (Matt Rourke/AP Photo), Gov. Tom Corbett (Matt Rourke/AP Photo), Mayor Michael Nutter (Matt Rourke/AP Photo) PFT President Jerry Jordan (Matt Rourke/AP Photo), and SRC Chair Bill Green (NewsWorks Photo)

For the Philly school district’s top brass, it’s a classic managerial quandary: Either, free up money for services or, hold off in hopes of securing long-term structural changes.

For Philadelphia school district superintendent William Hite, it’s a classic managerial quandary:

Either, grab some quick savings that could free up money for services that the city’s school children could really use.

Or, hold off on that deal in hopes of securing the long-term structural changes that you bet will strengthen the system overall.

The short-term money would come if the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers agreed to pay into their health care coverage.

The school district says that these concessions would generate “tens of millions” of dollars that could return “significant resources” to Philadelphia School District schools with the stroke of a pen.

In a city that’s seen severe budget cuts eviscerate traditional public school services and staff, Hite confirms that these savings would return additional guidance counselors, nurses, librarians and support systems to students who’ve starved for them through five months of what’s been called a “doomsday” school year.

The PFT’s contract with the district expired on Aug. 31. Shortly before then, PFT President Jerry Jordan said the union would be willing to take a pay freeze and make health care concessions, the size of which he wouldn’t define.

In a recent interview, Jordan said that if the contract hinged solely on health care concessions, “I think that we would probably be able to settle very quickly.”

Hite’s eyes are on the long term

But months have passed, with talks still in the “we’re at the table,” “negotiations are ongoing,” “there’s nothing to report” mode. This says a lot about Hite’s priorities.

He’s willing to take a pass on money in the “here and now” that would return badly needed services to students in order to keep leverage for the long-term structural changes he thinks will propel district schools into a higher stratosphere of academic quality.

“We’re negotiating a contract, not portions of things,” he said.

Chiefly, Hite wants a PFT contract that would give the district more of the managerial flexibility enjoyed by the city’s public charter schools – most of which employ a non-unionized workforce.

With these changes in work rules, the district could lengthen the school day and year, and assign, pay, transfer and lay off teachers based on factors other than seniority.

“We’re trying to get to a place where we have the ability to compete,” Hite said in a recent interview, “and that ability to compete is…to a large degree based on work rules that must change so that we can get certain individuals into certain buildings.”

The district has also asked the PFT to agree to 5- to 13-percent scaled pay cuts on way to realizing $103 million in annual savings.

Citing ongoing negotiations, the district will not reveal the exact make-up of its work-rule requests. An early draft of the district’s contract proposals was leaked last year. The district’s official word on the negotiations are as follows:

“We believe that a comprehensive resolution that includes economic concessions and work rule changes is critical for the short- and long-term benefit of our public schools….The District has to look past just the remainder of this year to next year and beyond.”

Some have criticized the PFT for not more readily agreeing to concessions.

At a televised press conference in August, Mayor Nutter said of the teachers union: “These are essentially the only adults at the table who so far have yet to financially contribute to a solution for this crisis…It is time for the PFT to step up.”

Corbett’s take

The Corbett administration is in lock step with Hite on the importance of securing work-rule changes above and beyond these savings.

“If you’re going to have a vibrant public school system going forward in Philadelphia, you not only need to generate these savings, but you’ve got to be able to operate the system in the schools in a way that’s actually going to deliver quality,” said state budget secretary Charles Zogby.

“I think the superintendent quite rightly sees the work-rule changes as an essential component of that,” he said.

To PFT president Jordan, the entire work-rule debate is a red herring that distracts from what he believes is the root of the district’s problems: inadequate funding.

“We’re willing to make some sacrifices in order to get through this very difficult time that the district is having, but the employees didn’t create it,” he said, “and the employees should not be viewed as a sustainable funding formula for the school district of Philadelphia.”

Reform debate

This is not the first time that Philadelphia’s students have been caught in the middle of a reform debate.

Earlier this school year, the Corbett administration withheld $45 million from the district through the first six weeks of classes. The money became available to the state’s budget over the summer after the Obama administration, specifically seeking to help Philly schools, forgave a federal loan.

At the time, among other cuts, the majority of district schools did not have a full-time guidance counselor. The state promised to withhold the dollars until the Philadelphia school district adopted a “reform agenda” to its liking – with the elimination of seniority chief on the list .

When the state announced it would release the money on Oct. 16, it cited a list of reforms that occurred before the school year began. Some attributed the state’s decision to the fallout that ensued after a 12-year-old girl died of an asthma attack after leaving a West Philadelphia elementary school lacking a full-time nurse. Corbett administration officials said there was no connection between the two events.

Mutual consent

Ideally, reformers would like to see the district use a system of “mutual consent,” where prospective teachers and hiring principals agree on each and every staffing placement.

All too often, proponents of the changes say, seniority-based systems give longer-tenured teachers the “best” jobs in high performing schools, while struggling schools are plagued with high rates of employee turnover.

Would diminishing (if not eliminating) seniority protections correct this inequity and improve academic outcomes overall?

Researchers who’ve studied this proposition have arrived at data-based conclusions both for and against.

Teachers often point out that high-performing suburban districts often achieve stellar results with seniority-based contract models.

“Broadly speaking, the finest public schools systems in this country, including the finest districts in Pennsylvania, all operate with these rules,” wrote South Jersey teacher and union consultant Kevin Parker in an email. “Thus, the quality schools are not causally linked to greater ‘flexibility’ in hiring. Here, as in the private sector, such flexibility is merely a euphemism for diminishing workers’ rights.”

Bruce Baker, professor at Rutgers University’s Graduate School of Education, argues that the tools the district would use to measure teacher effectiveness are flawed.

“This idea that they’re going to take this awful measure – this arbitrary measure of ‘seniority’ – and replace it with ‘effectiveness’ is built on a false assumption that we’re taking a meaningless measure and replacing it with a good one,” said Baker.

Proponents of revamping teacher work-rules claim that the current PFT contract “feeds a compliance driven bureaucracy” that’s unable to face the unique challenges of urban education.

“There is data that show that middle-and-upper class students can get a good education in a traditional teacher contract environment,” said Mark Gleason, executive director of the Philadelphia School Partnership. “That data does not exist for low-income minority students.”

Lessons of the ‘Renaissance’

Some insights in this debate can be gleaned by analyzing the performance of the district’s “Renaissance” charter schools.

Under the Renaissance model, select low-performing district schools have been turned over to charter organizations who, sans teacher union, have operated with all the workforce-related flexibility they’ve desired. These schools also tend to receive more resources via federal turnaround grants and private philanthropy, and employ many more support-staff administrators than can be afforded by district schools.

According to a recent report authored by the Philadelphia School District’s Office of Research and Evaluation, the academic results of the renaissance initiative have been mixed, largely depending on the organization operating the charter.

Mastery and ASPIRA have seen mostly double-digit gains in student performance on standardized tests, while providers such as American Paradigm, Universal and String Theory have seen some scores dip below district-run levels.

So what do these mixed results tell us about the push for altering work rules?

“Flexibility does not automatically translate into results,” said PSP’s Gleason, “but it’s a pre-condition.”

Despite multiple requests, the district did not comment on its views regarding the renaissance report.

Gleason says work-rule changes would give Hite the opportunity to vastly improve the system, “but management still has to take advantage of that opportunity by investing in great people and creating conditions that retain great people.”

“I don’t think this is about taking something away from teachers,” he stressed. “It’s about making schools better for kids and for teachers.”

But can the Philadelphia School District’s leadership be trusted to deliver on that promise?

“I’m not really capable of answering that yet,” said Gleason. “I think it’s too early to say.”

Tough sell to teachers

That lack of certainty doesn’t sit well with many teachers and advocates of traditional public education, who feel the proposed concessions will make the already difficult job of teaching in Philadelphia even less desirable.

“They make us uncompetitive, make us undesirable. [Ending seniority has] never been shown to improve the quality of the teaching force,” said Helen Gym of Parents United for Public Education, who called the suffering of students a “very calculated” attempt to “create divisions.”

“It is feeling like it’s using and exploiting the situation with our young people as a means for union bashing and stripping long-standing protections from Philadelphia’s teacher force,” she said.

Temple University professor Susan DeJarnatt says she becomes especially frustrated when she hears the reform debate devolve into the heads I win; tails you lose logic of being ‘for’ or ‘against the children.’

“As if anyone who opposes that thing doesn’t care about children,” said DeJarnatt. “It’s very effective as a rhetorical device. It makes them sound like no one would be against these ideas except for lazy teachers who are standing in the way of children succeeding and only care about their own paychecks, but I think that’s a really false image of what’s going on in public education today.”

According to the Pennsylvania School Boards Association, teachers in Philadelphia earn on average 19-percent less than their counterparts in the suburbs.

‘All the work-rule changes we want’

In some cases, the district has already assumed certain powers related to teacher work-rules.

In August, the School Reform Commission voted to suspend part of the Pennsylvania school code in order to rehire laid-off staff without regard to seniority. (The district abided by seniority-rules when shifting staff around during October’s leveling process.)

But thus far, despite some calls to do so, Hite and the SRC have refrained from “the nuclear option” of imposing a contract.

Asked about the district’s ability to unilaterally impose contract terms, Hite said in an August interview, “I’m not even sure that’s a true statement that that power is even available.”

If the district were to impose a contract, the PFT would likely sue, resulting in a protracted and costly legal battle in the Pennsylvania Supreme Court.

To newly appointed SRC Chair Bill Green, that’s a highly unnecessary proposition at this juncture.

The very fact that the teachers contract has already expired gives the district broad powers, he says, under Act 46, section 696 – the legislation that paved the way for the creation of the majority state-run School Reform Commission in 2001.

“The fact of the matter is, without a contract we have all the work-rule changes we want under 696, obviously that’s not the conditions upon which we’d like to get them going,” said Green.

Green emphasized that work-rule changes alone wouldn’t save the district, citing the need for more resources and the creation of a district-led climate of learning. Still, he said, giving principals the power to “put together a team” is “key” to the district’s overall improvement.

“We can not provide the education that our students deserve with the current work-rules. I truly believe that,” said Green. “Our goal is to have great district schools – 100-percent of our schools to be great schools – and that’s going to require cooperation from everyone.”

Green believes that the district can extend the school day and year without increasing costs.

Michael Masch (former state budget secretary, district CFO and SRC member) has spent time negotiating with the PFT during past collective bargaining agreements.

“I think there’s many, many things inside that contract that should change,” he said.

But he disagrees with Green that the district has “all the work rule changes” it wants.

“It is at least debatable,” said Masch. “It is not at all clear that the SRC actually has the right to impose these terms.”

Masch believes the district had the right to impose contract terms when the SRC was first established, but he believes the legal language of 696 suggests the district forfeited that right once it ratified a new PFT contract in 2003.

Despite being critical of some provisions of the current PFT contract, Masch thinks the district and the state have a lot of “gall” to ask teachers to agree to their concession requests.

“It is really chutzpah,” said Masch, “to say to these teachers, ‘You have the toughest job as a public school teacher in the state, you make less money already than suburban teachers, and we’re going to cut you even more…and we will unilaterally decide if you will keep your jobs or not.'”

Should I stay, or should I go…?

Despite a year of draconian budget cuts, the district’s financial picture is again looking bleaker than ever – with the possibility of more cuts looming on the horizon, and a proposed governor’s budget that adds zero additional funding to the state’s basic education subsidy.

To make matters financially worse for the district, its traditional schools lost more students to charters this year than they had anticipated–a wave that will cost $25 million in excess of budget projections. Overall, the district will spend $700 million this year on charter payments. (The state used to partially reimburse districts for their charter payments, but Gov. Corbett scrapped that funding stream.)

At this point, the powers-that-be steering the Philadelphia’s school district’s ship – including Hite, Green, Nutter and the Corbett administration – believe that vastly altering teacher work-rules will go a long way to creating schools that will convince families to stay.

“The school district has to find a way to produce better results,” said PSP’s Gleason. “That’s what will keep families in the system, and that’s what will make the system financially viable.”

In the meantime, as the district’s vastly under-resourced schools limp through the remainder of the school year, the district doesn’t know if parents are being given more and more reasons to walk away.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.