False promises? Recipients of Philly’s gun violence grants are still spending their own money

Philadelphia has set aside funding for community groups combating gun violence. But nonprofit leaders say actually getting the money has been a challenge.

Listen 4:14

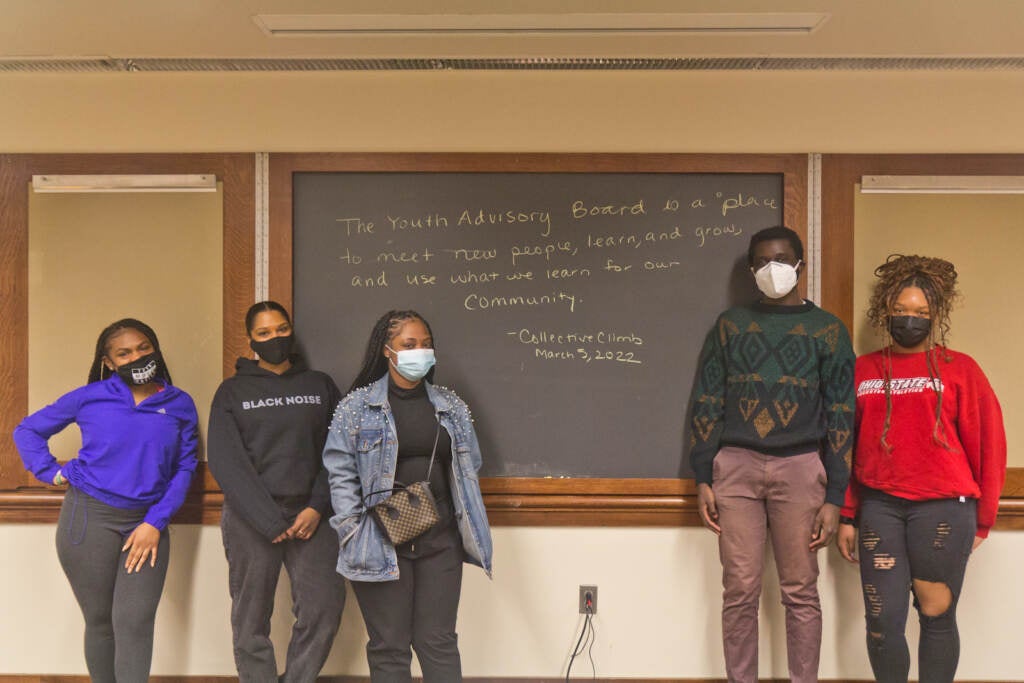

Mckayla Warwick is the executive director of Collective Climb and one of its co-founders. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

At Collective Climb, a Philadelphia nonprofit that runs healing circles and restorative justice programs for teens, business manager Kwaku Owusu has been tied up in email and phone exchanges most days, trying to secure the funding the group was supposed to receive this winter from a city grant program aimed at preventing gun violence.

“It’s extremely frustrating when our youth may need help or assistance or there’s other programming that we could be focusing our time on, and I’m spending days doing these administrative forms,” Owusu said.

The city has made grants to community groups a staple of its plan to bring down surging rates of gun violence in the city. The annual shooting tally increased 76% between 2016 and 2021, according to data from the Philadelphia Police Department.

In September 2021, the city announced the recipients for the fourth round of Targeted Community Investment Grants, which provide between $10,000 and $45,000 dollars to nonprofit groups promising to execute anti-violence programs. Those 41 organizations were required to report their progress back to the city by the end of February.

But multiple grantees say the payment process has been complicated and backlogged, to the point where they’ve stopped turning to the city for financial support and instead self-funded their programs or sought private donors. They say the city needs a more seamless process if they really want to support grassroots leaders.

“This timeline of this process should have been done in December,” Owusu said. “We’ve had to wait until probably March to receive the final bits of funding and all the tools that we need to carry out a program which is now already finished.”

Under the grant structure, nonprofit groups can choose to front the money and get reimbursed, or have a fiscal sponsor make purchases on their behalf. Owusu’s group chose the fiscal sponsor model, but said that by early March, only about two-thirds of the total dollar amount they were awarded had been paid out.

The city set aside $900,000 for the grant program, of which about $660,000 was earmarked for the grants themselves — the rest was set aside for expenses, such as staffing. So far, the Urban Affairs Coalition has distributed roughly $450,000 of the grant-specific funding — this figure doesn’t include the most recently filled reimbursement requests.

Erica Atwood, director of the city’s Office of Policy and Strategic Initiatives for Criminal Justice and Public Safety, said she’s aware of the problem and apologized for any “hiccups” in the rollout.

“I won’t make excuses for the challenges that our grantees have faced, that has never been our intention in how we wanted their experience to be,” Atwood said.

‘False promises’

Nonprofit groups interviewed by WHYY News said they experienced significant delays while waiting for the city and its nonprofit fiscal sponsor, UAC, to distribute checks. Several individuals said they had to use their own money or lean on private donors to keep their programs afloat.

Asinia Abdul-Wakeel, director of youth empowerment program SAPHE Haven, said he spent over $2,000 of his own money on recruitment flyers, workshop supplies, gift cards, and food for the education series he launched after being notified by the city about the grant.

He said the city and the UAC initially told him it would take 15 business days to get reimbursed. But it actually took several months; he didn’t get most of his requests fulfilled until mid-February.

“It’s always this empty apology, with no explanation for why it happened,” he said.

Atwood said the coalition has been experiencing delays and technical difficulties due to the coronavirus pandemic and remote work.

The UAC noted that at one point in September 2021, it had only one staff member due to turnover and absences. It also halted reimbursements for three weeks toward the end of 2021 as it transitioned to a new fiscal system.

“There tend to be errors on both sides,” Atwood said. “We want to make sure that we do what we can as their support in this process to mitigate those hiccups and those missteps.”

Mckayla Warwick, executive director of Collective Climb, said she still owes payments to venue owners from the teen program she ran using the city funding.

“There have been a lot of false promises made to young people,” she said. “Unfortunately, our young people kind of expect that at this point. It’s never a surprise when things go wrong.”

Elizabeth Clinton, development manager for a nonprofit called Safe-Hub Philadelphia, which runs sports programs for teens, said they also expected to be reimbursed for the cost of equipment within two weeks of making purchases.

But when they would submit forms, there was confusion about where to send them and what information should be on them.

And when there was a problem with something they sent in, “you might not hear about it until a few weeks later, at which point we’re a few weeks delayed on the next reimbursement,” she said.

UAC said it pays grant recipients within 15 business days of receiving their reimbursement requests if the paperwork was completed correctly.

As of the end of February, Clinton said they had not received any payments.

She said the UAC instructed them to spend the total amount of their grant — $17,000 — in order to be repaid, and promised to reimburse those costs by the end of March.

“I know that they have lots more payments to process, so [I’m] definitely hoping for the best in that situation.”

Support for smaller nonprofits

The city provided two liaisons to help grantees with reimbursement and purchasing, which some nonprofit groups said they found helpful when filing their expenses.

But how successfully an organization can navigate the process depends a lot on how large the organization is, how much money they have on reserve, and how much time they have to communicate with the grantmaker.

Angenique Howard, chief executive officer of Unique Dreams Inc., said she couldn’t use the grant to purchase equipment for her organization’s boxing program, and instead partnered with another organization to provide it. She said the reimbursement process could put smaller organizations in a tricky situation financially — they may not have the cash on hand to foot every purchase necessary for operating new programs.

“That’s a difficult task for a nonprofit, especially a smaller nonprofit, to be able to have those funds available,” Howard said.

Howard says she’d like the city to think more closely about the grant distribution process going forward, and to ensure that the money is accessible for grassroots groups that may not have the capacity to navigate the bureaucracy often involved in grant payouts.

Alyson Ferguson provides evaluation and support to community groups through the Scattergood Foundation. She said funders need to provide technical assistance to nonprofits in addition to funds.

“Folks wear many, many hats within nonprofits and we don’t make it easy for them when it comes to grant contracting,” she said. “We need to be conscious as funders of when we do offer capacity-building, that we make sure there’s support for staff time or even coverage for an individual to go and think through the opportunity or to work with the liaison.”

She said in an ideal world, funders would provide the full grant amount to organizations at once, and then ask for proof of spending at the end.

“I think it’s time now for both government entities and philanthropies to trust the nonprofits that are doing the work on the ground,” she said. “And focus on providing enough dollars upfront to really have organizations have a runway to get their work up and running.”

Looking ahead

Atwood said she’s keeping critiques in mind as the city moves forward with plans to support community gun violence programs.

In July, the administration set aside $20 million for Anti-Violence Community Expansion Grant awards. Of that, $13.5 million goes directly into grants for organizations, and the rest is set aside for evaluation and technical assistance.

The new awards are much larger than the Targeted Community Investment Grants. Community Expansion Grants range from $100,000 to $1 million.

Atwood says the city has supported the UAC in hiring additional staff — program managers and communications specialists — so they are able to more effectively assist grantees.

She said she aims to “avoid continued stress and trauma to our community-based organizations and so they can fulfill their programming to the communities that need that programming the most.”

In January, a UAC survey found that a majority of CEG grantees are at least somewhat satisfied with the service they received during one-on-one meetings. However, the results are based on responses from only 13 of 49 grantees.

As for the Targeted Community Investment Grants, Atwood says she’d be “relentless in trying to make sure that our grantees get paid.”

For future Targeted Community Investment grant recipients, the UAC is creating training videos and adding documents to a self-service portal to provide them with information about the full grant process.

New Leash on Life USA, a nonprofit group that helps rehabilitate people with criminal records by teaching them to care for rescue dogs, received both a Targeted Community Investment Grant and a Community Expansion Grant.

CEO Marian Marchese says they had a positive experience in both cases and were able to use the money from both awards to hire an additional social worker, add participants to the program, and pay for a third-party evaluation of the results. She said the requirements for receiving the funds were not as onerous as what she’s seen with other grants.

“While the city is being very prudent on everyone providing the right kinds of receipts and the vouchers and the timesheets so that everything can be monitored, they’re also letting you do your job so that you can have success for why they selected you in the first place,” she said.

The Greater Philadelphia YMCA received a Targeted Community Investment Grant to help provide resources for teenagers and young adults affected by gun violence. Like New Leash on Life, they’ve had a positive experience with the grant — complimenting the support they received from the grant officer the city assigned them — but noted their experience may not reflect that of smaller organizations.

“You want to make sure you have a healthy mix of organizations,” said Tiffany Thurman, vice president of government affairs at the Greater Philadelphia YMCA. “It’s gonna always be a challenge for the city to strike that balance when they’re working on grant allocation. Do you provide funding to the big organizations that have the capacity and resources to implement robust programming, or do you take a more grassroots approach?”

As of Jan. 20, the city had distributed roughly $792,000 of the $13.5 million set aside for the Community Expansion Grants. The city will work with the UAC to distribute the rest of the funding to nonprofits over the course of the year-long grant cycle, which closes this November.

Amelia Winger contributed to this report.

___

If you or someone you know has been affected by gun violence in Philadelphia, you can find grief support and resources here.

This article is part of The Toll: The Roots and Costs of Gun Violence in Philadelphia, a solutions-focused series from the collaborative reporting project Broke in Philly. Find other stories here and follow on Twitter at @BrokeInPhilly.

This article is part of The Toll: The Roots and Costs of Gun Violence in Philadelphia, a solutions-focused series from the collaborative reporting project Broke in Philly. Find other stories here and follow on Twitter at @BrokeInPhilly.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.