Back to his banker roots, former Philly Zoo CEO looks to shake some difficult money trees in next adventure

Longtime Philly Zoo CEO Vik Dewan is not retiring. Instead, he wants to crack open obscure funds to increase charitable giving sooner rather than later.

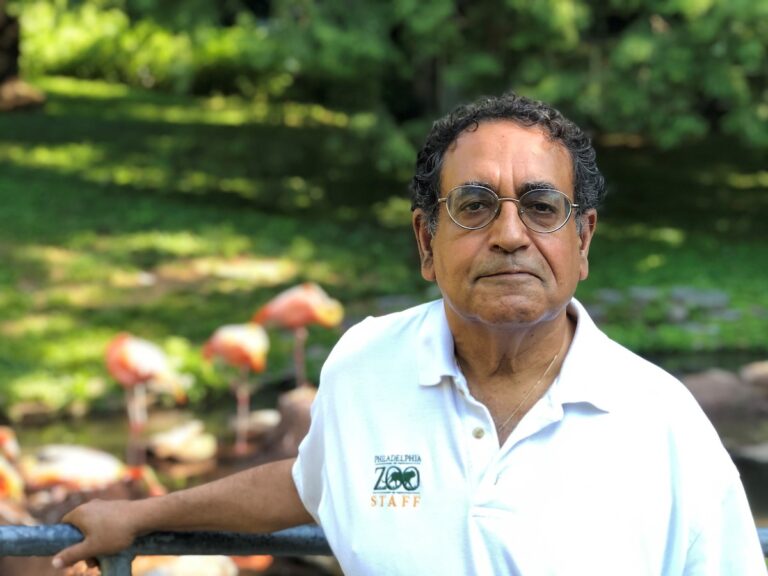

Vik Dewan served as the CEO of the Philadelphia Zoo for 16 years before he stepped down in 2023. (Courtesy of Philadelphia Zoo)

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

Vik Dewan has spent countless hours over the past 16 years with more than 1,900 animals who live behind the Philadelphia Zoo gates year round as its CEO.

The iconic 42-acre park in West Philly is bustling with visitors on summer days when school is out. That’s also when many animals are awake, or at least sunbathing, especially those who thrive in tropical climates.

It’s because all the animals have different ambient temperature preferences. For example, giraffes are likely indoors when it’s colder than 50 degrees outside.

But for Dewan, the outgoing CEO of the Philly Zoo, he prefers the colder days when he can see the tigers — native to communities where forests are blanketed in snow — shine in their habitat.

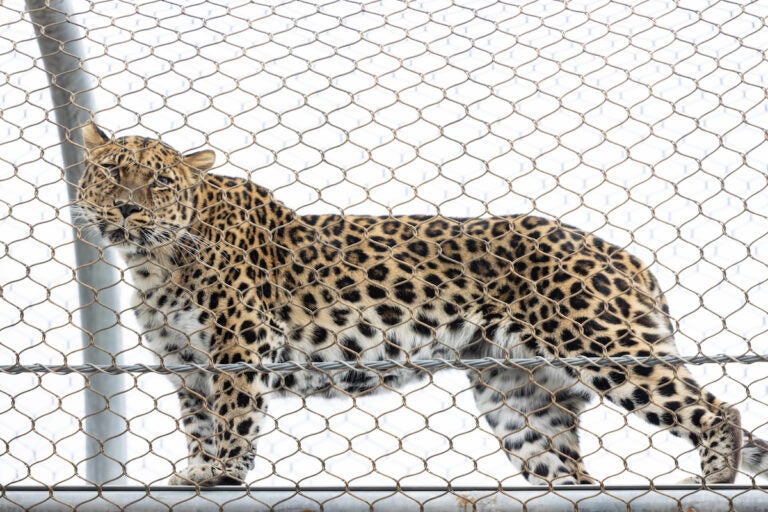

“I love that first snow. Our zookeepers will build our tigers a snowman and they will pounce on it,” he said. “To see our Siberian [Amur River Valley] tigers come out into the snow and play. They are a blaze of orange and black against the white snow. It’s just unbelievable. It just takes your breath away.”

That’s in part because Amur tigers — the largest living cat — are an endangered species; there are an estimated 400 tigers left in Russia.

Dewan was the first Philly Zoo CEO who didn’t have an educational or professional background in wildlife preservation or even animal studies. He was a banker for Wachovia, now Wells Fargo, serving as the president for the bank’s Philadelphia and Delaware region when he was tapped as the zoo CEO in the mid-2000s.

At the time, his world was about capacity, capital, conditions and collateral — typical metrics used when bankers underwrite a loan to a business — in his role overseeing 100 branches and more than 1,000 employees.

But Dewan has since added another dimension — community.

During his tenure at the zoo, he oversaw a zookeeper diversity talent pipeline program.

“It became very easy to pick the person who had the longest list of internships — the vast majority of which were unpaid,” he said about the competitive hiring process for zookeeper jobs. “What we realized is that we were creating this economic barrier for many people to enter this profession.”

There’s now paid internships for high school and college students hailing from the neighborhoods of Brewerytown, Fairmount, Parkside, Mantua and Belmont, which surround the zoo in West Philly.

He’s also credited with reimagining how visitors experience the zoo while stabilizing a boom and bust cycle of attendance and revenue.

“We started to think about [the zoo] in three dimensions and we built these overhead trails that connected the animal habitat area, giving animals the ability to roam between exhibit areas,” he said about something that now 60 zoos worldwide have adopted.

In Philadelphia, it’s also an urban zoo where many local visitors “will not get a chance to [travel] to Brazil, Indonesia or Australia to see the magnificence of our planet up close” but those trail systems help close the gap.

Over the years, he also supported an effort to source food for the animals from local suppliers within 100 miles of the zoo.There was even a hydroponic farm plan where local neighbors could grow food and sell it to the zoo for animal feed as an economic development effort that would be a business with a social impact.

Now Dewan, after restructuring the financial model of the zoo for sustainability to keep supporting animals like those tigers, is turning his gaze to all nonprofits, which he’s concerned are just as endangered.

“Nonprofits don’t fail because of the urgency of their mission or the things they’re working on,” he said. “It’s because they don’t have the financial resources to really be able to pull off what is oftentimes a long-term mission.”

Dewan said he’s noticed the available pool of money to promote social good is shrinking rather than growing.

“Philanthropy in the United States has hit a wall,” he said. “It is stuck at $500 billion.”

The Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy in Indianapolis tracks all types of charitable giving, including individuals, foundations, corporations and legacy gifts, or money left in wills. In 2022, there was an estimated $499 billion donated to U.S. charities down from $516 billion in 2021.

One reason was poorer stock market performance but also high inflation for individual donors — which accounts for $319 billion in donations nationwide — declined by 13.4% when adjusted for inflation.

Donations to environmental and animal organizations, like any zoos, declined to $16 billion when adjusted for inflation — that’s a nearly 9% drop.

There’s a shift where many ultra-wealthy individuals have decided to park money inside of donor-advised funds instead of foundations, which are required to grant at least 5% of their assets each year, in accordance with the Internal Revenue Service.

In 2022, contributions to donor-advised funds hit $86 billion — which is $8 billion more than in 2021 — according to the National Philanthropic Trust.

There’s interest in donors stashing money in these special funds because there’s the ability for individuals to get bigger tax deductions than a traditional foundation and there’s fewer rules about transparency of who the donors to a fund might be.

Sometimes private foundations hit their payout requirement by donating money to these donor-advised funds which don’t have to be granted to any nonprofits so it’s a closed loop system.

“Once you set up a donor advised fund you don’t have to grant out anything if you don’t want to,” Dewan said. “We have a large pool of money marooned out there. It’s not being granted out. [Donor-advised funds] are not family foundations. They don’t have time limitations.”

Now the goal is to start meeting with donors to offer insight about what’s possible. And he’s got one foot in the door. In 2014, Dewan was tapped to join the board of trustees of Vanguard Charitable, a donor-advised fund based in Malvern.

Dewan lauded Vanguard’s efforts as a sponsor for donor-advised funds — which means it’s a fund manager — because it does make regular grants despite not being required to do so under tax law.

For example, its donors granted more than $2.6 billion to nonprofits in 2023, an uptick of 39% compared to 2022.

He stepped down from his role as a trustee at Vanguard Charitable last year after serving his term.

“We’re not competing with any other foundation,” Dewan said. “We’re trying to give [nonprofits] new sources of funding that we think can make change in this region.”

Saturdays just got more interesting.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.