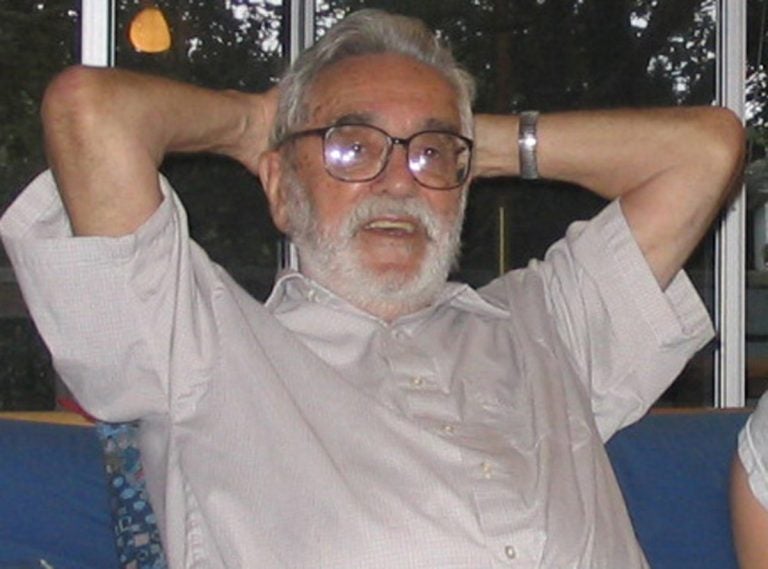

Philadelphia therapists reflect on legacy of innovator Salvador Minuchin

The psychiatrist and innovator in the field of family therapy died last week at the age of 96.

Salvador Minuchin (CC BY 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=742801)

Salvador Minuchin, an innovator in the field of family therapy, died last week at the age of 96.

The psychiatrist spent many years in Philadelphia, as a professor at the University of Pennsylvania and the head of psychiatry at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. He also worked with children in Israel who survived the Holocaust and with kids from Harlem whom society dubbed “delinquents.”

From those experiences, Minuchin developed techniques to work with struggling families. Unlike most therapists of the day, he believed in looking at people as more than individuals.

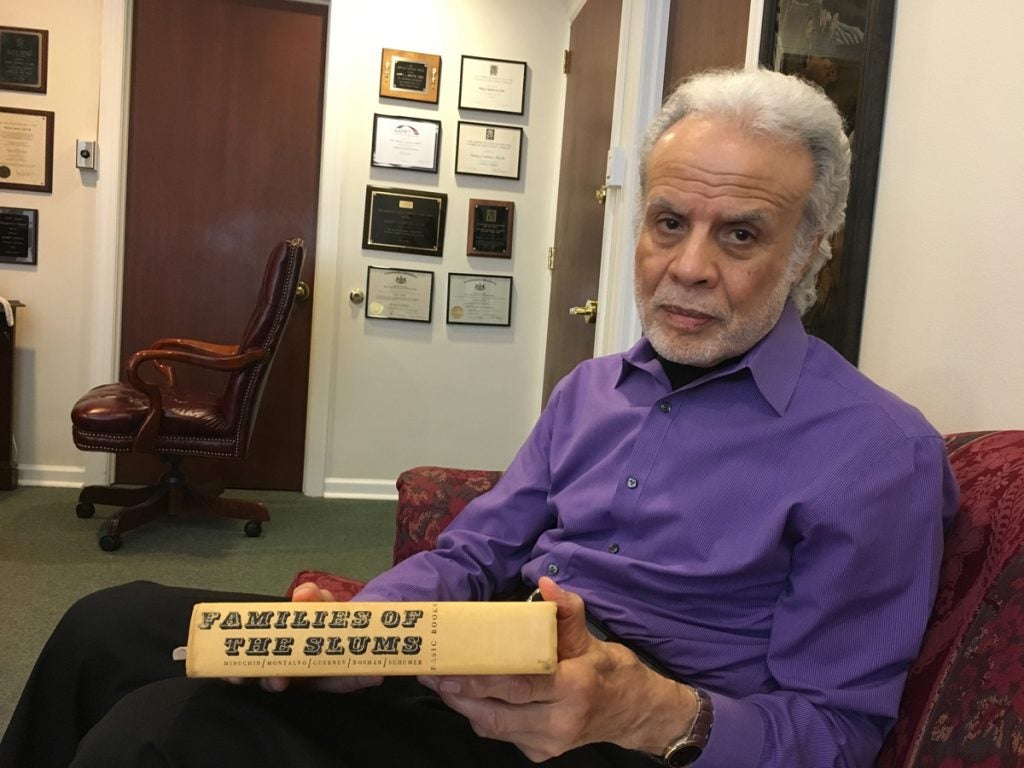

“Sal would connect with people. I mean, he got them really engaged,” says Harry Aponte, a marriage and family therapist who worked with Minuchin in the ’60s.

Minuchin was treating families where the parents didn’t have enough power, or the kids were taking on too many responsibilities, Aponte said. Minuchin came to see the therapist’s job as creating rules for the family so healthy patterns could develop.

But to do that, the therapist couldn’t sit back and observe; he had to engage with people and sometimes “join” the family during a session.

“He often talked about it as if it were a theater,” said Aponte. “And you’re part of the theater, and you can be the director, but you can also become an actor in it, so that you create an experience that has a real impact on them.”

The idea that therapy is an experience — and not just a conversation — has informed Aponte’s practice and what he teaches his family therapy students at Drexel University.

Many of Minuchin’s techniques and beliefs are so ingrained in mainstream therapy today that, these days, providers tend to take them for granted, Aponte said.

Marion Lindblad-Goldberg, who directs the Philadelphia Child and Family Therapy Training Center, worked with Minuchin at the Child Guidance Clinic.

Lindblad-Goldberg called him a social justice advocate. Minuchin believed that mental health was driven not only by families, but by larger communities, race and class, she said.

Change, Minuchin thought, came through working with the people in someone’s life.

“His legacy is that you can’t help people without looking at the relationships they’re in,” she said. “If you want to create change in someone’s life, you need to work with the people that they are connected to.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.