A Philadelphia surgeon’s invention and historic open-heart operation is celebrated 70 years later

Dr. John Gibbon invented the heart-lung machine and used it to perform the world’s first successful open-heart surgery on May 6, 1953.

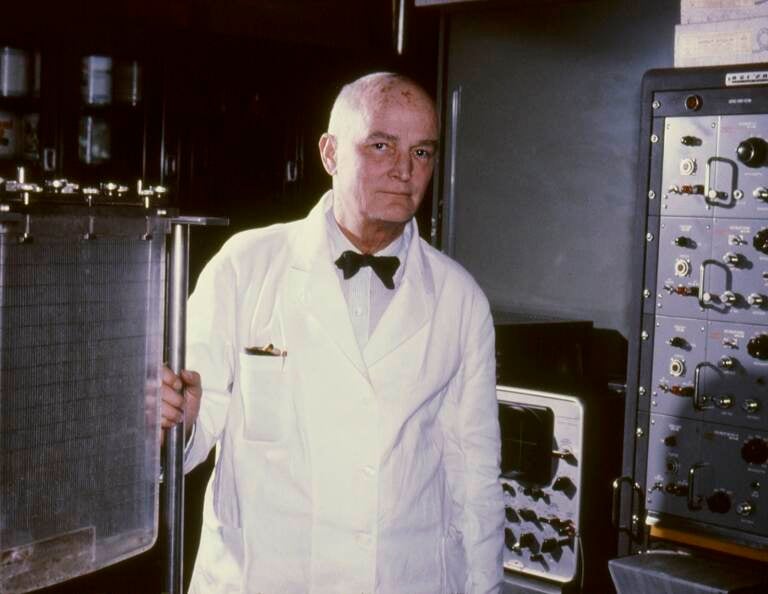

Dr. John Gibbon was a researcher and surgeon at Jefferson Medical College Hospital in Philadelphia. He invented the heart-lung machine. (Courtesy of Thomas Jefferson University Archives, Philadelphia)

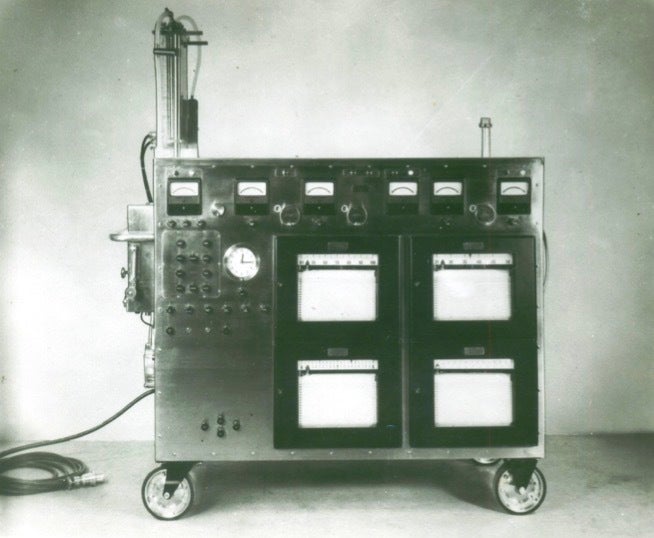

On a recent Monday morning in a simulation lab at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, Brian Schwartz attached clear tubes of all different sizes to a large machine with several monitors, dials, and pumps.

During a real surgery in a hospital operating room, those tubes carry blood back and forth between a patient’s body and a heart-lung bypass machine, which oxygenates and circulates the blood so that surgeons can work on the heart.

Schwartz is a perfusionist, a professional who operates these machines.

“Our field is very young actually,” said Schwartz, who is program director of cardiovascular perfusion at Jefferson. “And ironically, the first open-heart surgery that was performed utilizing the heart-lung machine was right here.”

Seventy years ago this month, Philadelphia researcher and surgeon Dr. John Gibbon used his invention of the heart-lung machine to perform the world’s first successful open-heart surgery on an 18-year-old woman at what was then called Jefferson Medical College Hospital.

The procedure and use of the machine was the beginning of many more successful surgeries and medical advancements. More than two million people worldwide undergo open-heart surgeries each year, according to the National Institutes of Health.

Over the years, scientists built upon Gibbon’s early invention to create the modern-day heart-lung machine.

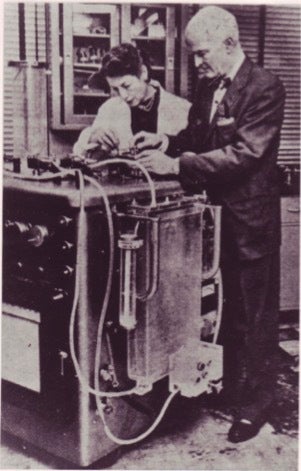

“I’m blessed to teach at an institution where the first heart-lung machine was utilized,” Schwartz said. “And the coolest part about that story is that Dr. Gibbon’s wife was his perfusionist.”

Gibbon spent much of his career searching for a way to perform complex procedures on the heart to fix serious cardiovascular diseases and issues, many of which were fatal at the time.

Congenital heart defects, damaged heart valves, aortic aneurysms, heart failure, coronary artery disease, and more can often be treated today with open-heart surgery.

To develop a heart-lung machine and test the device, Gibbon worked alongside his wife, Mary “Maly” Hopkinson, and other professionals to perform experiments using animals.

Their first human patient was a 15-month-old baby, who died during an operation in 1952. According to archived records, the baby’s heart defect was more serious than initially diagnosed.

On May 6, 1953, Gibbon used his heart-lung machine to operate on Cecelia Bavolek, an 18-year-old college student who had an atrial septal defect — a hole in her heart.

Gibbon put his patient on bypass for 26 minutes while he successfully closed the hole in Bavolek’s heart, which marked a turning point in surgical cardiac care.

In the following years, the Mayo Clinic picked up Gibbon’s research and his invention to improve the heart-lung machine and surgical survival rates.

Gibbon died at age 69 on Feb. 5, 1973. He suffered a heart attack while playing tennis in Philadelphia. Thomas Jefferson University honored the surgeon by later naming its hospital building at 11th and Chestnut streets after the pioneer.

Bavolek lived for at least another 50 years after her procedure that made history.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.