‘BOOM’: Philly Art Museum explodes with 1940s art and design

“BOOM” examines a lesser-acknowledged decade for creative innovation.

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

1940 was an anxious year for America. While still recovering from the economic devastation of the Great Depression, Americans were watching the rise of fascism in Europe and the start of a new World War, which the United States would ultimately enter.

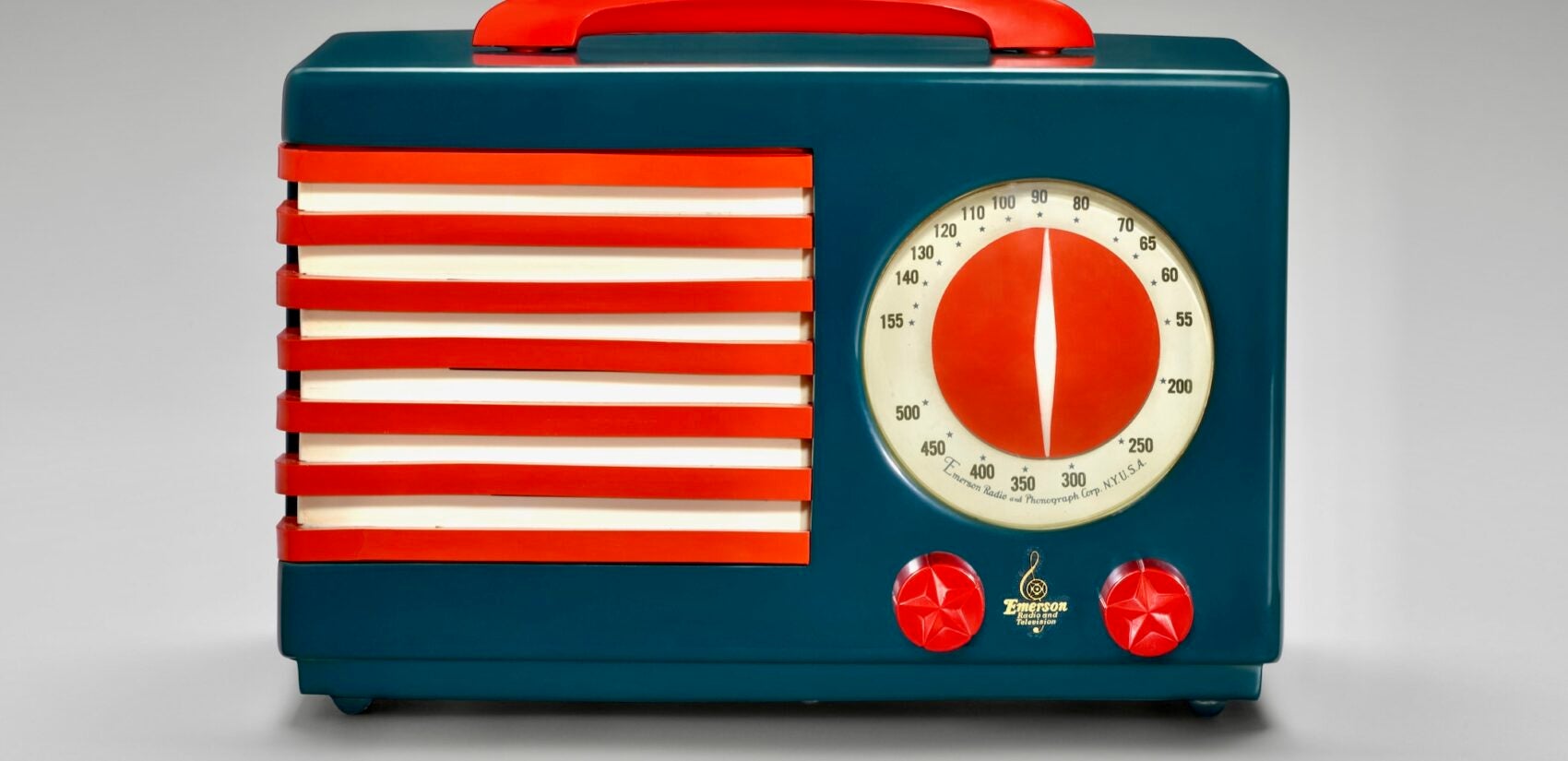

None of that is immediately evident when first stepping into “BOOM: Art and Design of the 1940s” at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, which greets visitors with a 1940 “Patriot Radio” by industrial designer Norman Bel Geddes playing period baseball games and popular hits of the day by artists we know by name: Ella, Frank, Perry, Doris, Dizzy, etc.

The Catalin plastic radio in the colors of the American flag are surrounded by paintings that literally dance: “Jitterbugs” (1940) by Reginald Gammon,” “Nightclub” (1942) by Abraham Hankins and “Jam Session” (1943) by Clause Clark, featuring a couple dancing the Lindy Hop.

“People cope in different ways. It’s part of the reason why we have paintings of people dancing,” said Jessica Smith, director of curatorial affairs.

“Georgia O’Keefe was spending the early half of the decade in the Southwest finding inspiration and solace from the environment around her,” she said, pointing to O’Keefe’s “Red Hills and Bones” (1941), a study of desert colors and topography.

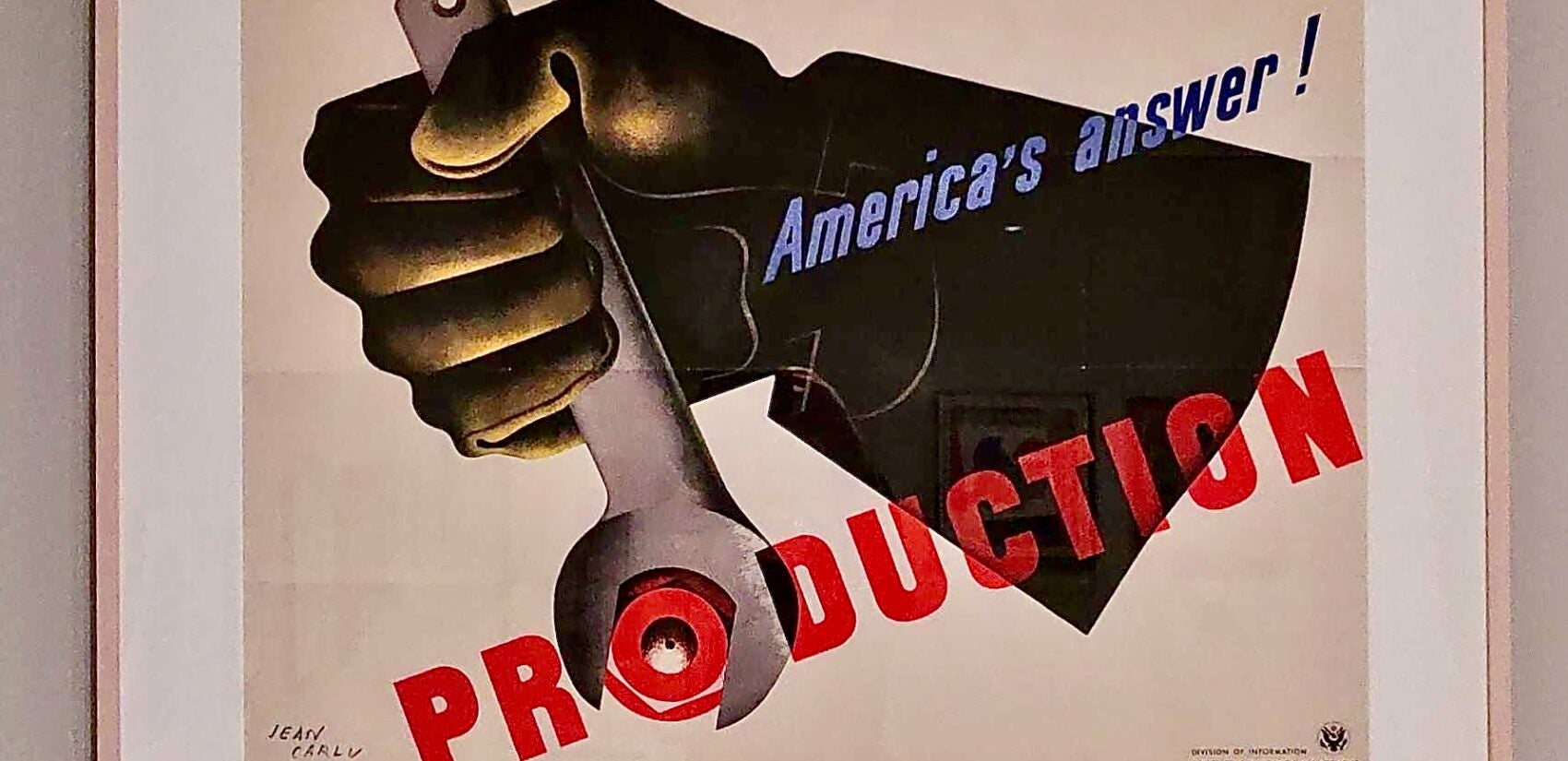

“The war was still there. It’s something that you’re dealing with either by moving towards and embracing with your iconography, or just the opposite,” she said. “There’s a whole gallery that is geometric abstraction. It’s shape and form and line and color, about as opposite from tackling politics as you possibly can imagine.”

“BOOM” has lots of stories to tell about a decade that started austere and ended at the Golden Age of Capitalism in the 1950s. All 250 objects on view come from the Art Museum’s collection. Smith pulled in nearly every department, including prints and photography, craft, decorative arts, fashion, furniture and housewares.

“It was extraordinarily fun putting together,” Smith said. “There is so much going on and obviously there’s no way we could tell all of the stories of the 1940s. But we tried to create a sense of the zeitgeist, the feeling of the time.”

The dresses are a showstopper in “BOOM.” In the second gallery is a lineup of dresses and women’s suits from the war period, including three designs produced by Elsa Schiaparelli who fled Paris shortly before it fell to the Nazis in 1940, establishing herself in New York.

The designs show the austerity of the day, when fabric was rationed for the war effort. Trimly tailored with little frill and no flounce, Schiaprelli’s suits have an almost masculine line.

“Fashion is born by small facts, trends, or even politics,” Schiaparelli wrote in her 1954 autobiography “Shocking Life.” “Never by trying to make little pleats and furbelows.”

One of her dresses features a red velvet waistcoat embroidered with tiny tubers, such as turnips and carrots. The museum’s curator of costumes and textiles, Dilys Blum, said it’s one of the most poignant Schiaparelli dresses of that period.

“It’s embroidered with vegetables, some of which may be seen in a victory garden. Although in France prior to this, they would have been considered cattle feed,” she said. “It was very much a statement about women’s roles in Vichy France.”

A later gallery focused on art and design explicitly reacting to the war includes a woman’s bathing suit made of maps of Europe. Soldiers sent into enemy territory were often given maps printed on cellulose fabric rather than paper, for durability in adverse conditions. With fabric scarcity at home, some of those maps were turned into clothes. The two-piece swimsuit was made by an unknown designer, likely the wife or girlfriend of a returning soldier.

Smith said art history often overlooks the early part of the 1940s in favor of the latter half, with the rise of Abstract Expressionism, arguably the most important American art movement of the 20th century.

“We felt that it was interesting to look at the 1940s as a whole because of a misconception that creativity stopped during the first half of the decade because of World War II,” she said. “So many projects look at 1945 and after. We really wanted to look more holistically at the 1940s because it’s such an important generative moment for innovations that people associate with later decades.”

Of course, Abstract Expressionism is in “BOOM.” Early works by well-known artists such as Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock, Lee Krasner and Judith Rothschild show the inventive work they were doing, which pushed New Yorker critic Robert Coates to coin the phrase “Abstract Expressionism” in 1946 because he did not know how else to describe this emerging style.

“BOOM” acknowledges that most people in the 1940s did not live in a world of abstraction. Jacob Lawrence’s “Libraries are Appreciated” (1943) depicts Black figures reading in a Harlem library. Many African Americans, like Lawrence, discovered Black history in libraries because it was not taught in schools.

Ben Shahn’s “Miners’ Wives” (1948) is a figurative work that communicates the grief of widows who lost their husbands in a catastrophic 1947 mining explosion in Centralia, Illinois, that killed 111 miners.

Many Americans will likely associate the 1940s with its post-war boom of retail consumerism. New materials in bright colors with whimsical designs dominated the modern home, or what the modern home aspired to be. A later gallery of “BOOM” is outfitted as a domestic showcase of curvy Eames chairs, day-glow Tupperware, bold Hans Hoffman abstractions, earthtone textiles and geometric patterns.

“A covered casserole made by Robert Turner. He was a conscientious objector during the war, but went on to become an artist teaching at Black Mountain,” said Elisabeth Argo, curator of craft and decorative arts. “Or you could have a Russell Wright [casserole] which was mass produced but designed for modern living.”

If you have a sharp eye and are very, very lucky, you may still stumble across one of these objects at the odd thrift store.

“The objects that you see in this room are really about living,” Argo said. “It’s about pivoting, coming out of adverse times and coming into the lives that we’ve enjoyed ever since.”

“BOOM: Art and Design of the 1940s” will be on view until Sept. 1.

Saturdays just got more interesting.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.