Petition drive would bring back nonpartisan elections to Camden

Activists say having a primary in a city mostly full of Democrats and independents doesn’t make sense. The primary turns into the main election.

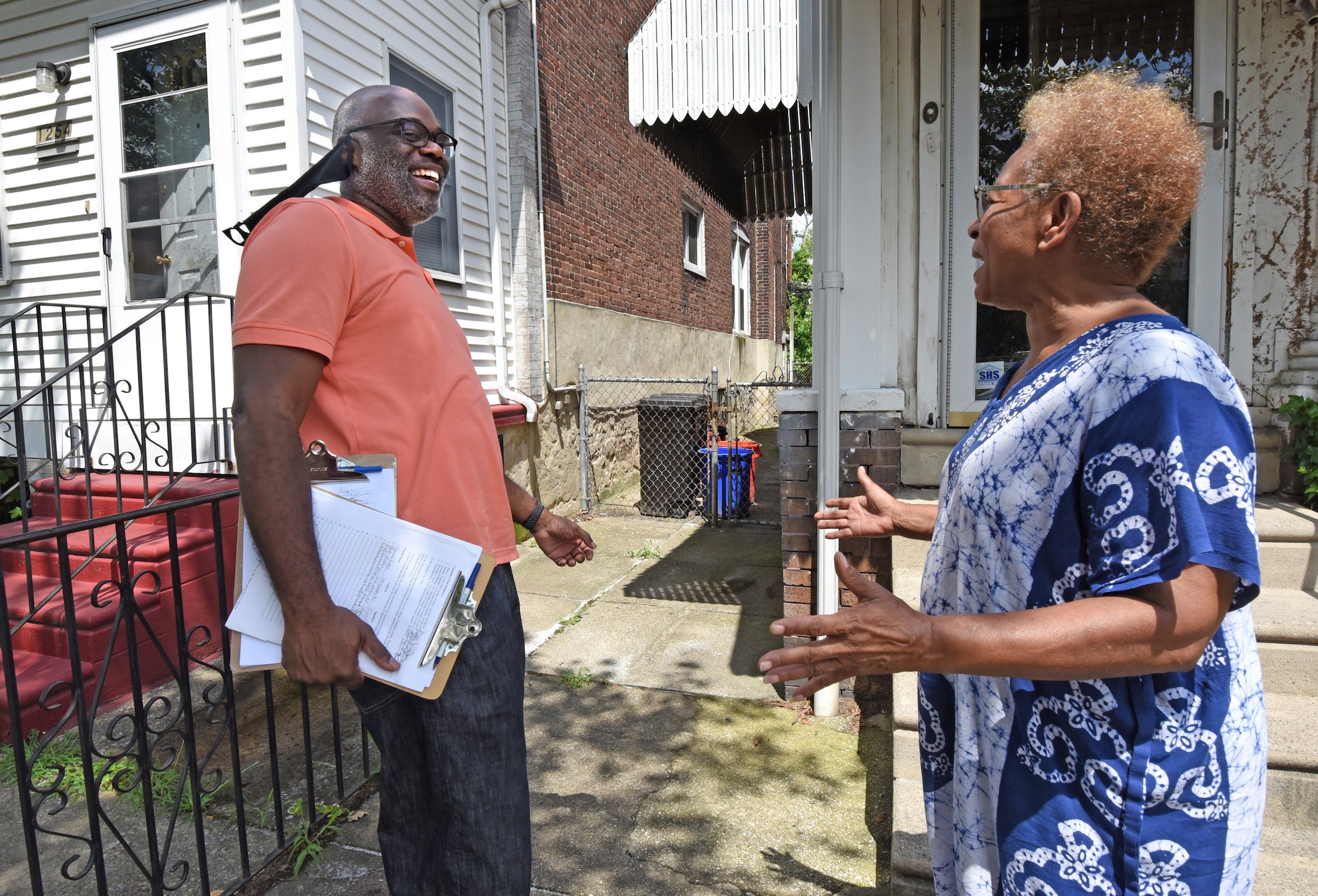

Residents meet in South Camden on August 6 to compile petitions they've circulated and plan strategy in an effort to return nonpartisan voting to the city. (Photo by April Saul for WHYY)

Ten men and women sit at a picnic table in a South Camden neighborhood on a warm August night, wearing face masks and thumbing through stacks of petitions.

But what they’re planning could change politics as usual in this city as much as any plot hatched in a smoke-filled room.

Led by former Camden Councilman Ali Sloan El, the activists are mounting an effort to bring nonpartisan municipal elections back to Camden after an absence of 13 years. The group plans to submit the petitions in time for consideration at the August 11 City Council meeting, and if the Council doesn’t approve the switch, the issue will appear on the November ballot to be decided by Camden voters.

In a city in which about half of voters identify as Democrats and half as independents with very few Republicans, the June primary is everything. The current partisan system, activists say, gives a huge advantage to candidates put forth by the powerful South Jersey Democratic machine who get preferred ballot placement, while independents rarely participate in the primary at all.

City lawmakers, said Sloan El, got Camden elections changed from nonpartisan to partisan in 2007, “by putting it on a ballot and telling everybody the city would save $80,000” by not having to hold an extra election.

“But they were really doing it because it disenfranchises half the city of Camden,” said Sloan El.

Independent voters, said Theo Spencer, a member of the petitioning group who is currently running for Camden’s school board, could vote in any primary by designating a party. “But if you’re an independent,” said Spencer, “you don’t even get any of the primary mail, so you don’t know. And in Camden, any little thing can be a disincentive when it comes to voting.” In a city of about 74,000, roughly 7,000 residents voted in last year’s November election.

According to Rutgers’ public policy professor Julia Sass Rubin, New Jersey’s unique ballot design has for decades created the greatest inequity in partisan elections. Instead of placing competing candidates in a list beneath the office they seek, like in every other state and the District of Columbia, the ballots in 19 of 21 New Jersey counties feature a slate of candidates endorsed by the Democratic or Republican Party and presented as a vertical or horizontal line of names — dubbed the “county” or “party” line. Candidates not on that line are put in other columns or rows, sometimes far away in what Rubin calls “ballot Siberia.”

“What this ballot does,” said Rubin, “is give the party chairs in most counties unbelievable control over who’s going to win the primary.” With one-party dominance in most of the state, she said, “you’re essentially placing people into office… So if you have the ability to decide who’s going to win, once they are elected, they are accountable to you, not the voters. And that’s essentially what happens in Camden.”

Many of the activists involved in the current drive believe unfair ballot placement has contributed to their own unsuccessful candidacies in the city. “I ran four times, they put me in the end of nowhere,” said Mary Cortes, president of the Cramer Hill Residents Association. “It’s easy to just go down the column to vote, you could have a pervert or a murderer on there!”

Currently, 14 of the largest 20 U.S. cities have nonpartisan elections — Boston, Chicago, and San Francisco among them — and in New Jersey, Newark, Trenton and Jersey City hold nonpartisan contests as well.

Camden had nonpartisan elections from 1960 to 1992 and from 1996 to 2007 — when city leaders won a referendum to return to partisan elections, said Vance Bowman, one of this drive’s petitioners, because “we didn’t fight it. Nobody was paying attention.”

In 2012, legendary Camden activist/lawyer, the late Frank Fulbrook led a petition drive for another referendum in an attempt to return to nonpartisan elections, but when he was hospitalized with a lung infection, the paperwork was submitted late. Camden lawmakers ruled that the group had missed the deadline for that year’s ballot, and that the question would appear on the 2013 ballot instead.

Then, in 2013, petitioners accused the Camden County Democratic Committee of flooding the city with pamphlets claiming that efforts to make elections nonpartisan were part of a Republican conspiracy to take over Camden and demanded an apology. Fulbrook died in August. Two months later, residents voted to keep elections partisan.

Camden Mayor Frank Moran sees no upside to nonpartisan elections. “In June and November elections,” he said, “the city isn’t footing the bill. When you have a totally separate nonpartisan election, the burden is solely on us.”

Camden Councilman Angel Fuentes agrees. “Where do we find $100,000 for an extra election?” he asked. “It forces us to make substantial cuts to programs that are badly needed in the city of Camden.” Both men believe that having multiple elections in one year actually discourages voter turnout.

The current petition drive, with 70 volunteers, began two months ago. The group needed to get a number of signatures equivalent to 25% of the voters in the last general assembly election, which amounts to about 1,750 names. Monday, they submitted them to the City Clerk in hopes of consideration at tonight’s City Council meeting.

If council doesn’t vote to approve the change, it would once again become a ballot question in November.

“They’re probably going to turn it down,” said Spencer, “because they benefit from the partisan election process.”

Spencer, like the others in the group, believes that nonpartisan elections would force party-anointed candidates to work harder to get votes.

“When you have a nonpartisan election,” Spencer said, “you have to walk the neighborhood. And some of the party candidates don’t really even live here!” The election would take place in May, he said, “so nobody can ride any coattails.”

Petitioners were encouraged by last year’s ballot question that ultimately returned the city’s Board of Education to elected, rather than appointed office, a few seats at a time. That measure passed by a two-to-one margin, in spite of opposition from Mayor Moran and other sitting lawmakers. If the nonpartisan question passes, noted Spencer, law dictates that “it can’t be changed for ten years.”

As they gather signatures, the group has also registered 175 new voters, many of them on probation or parole who didn’t realize recent legislation had granted them the right to vote. That was particularly satisfying for Ali Sloan El because he spent 18 months in prison after pleading guilty in 2007 to taking $36,000 in bribes for promising to steer public work to a contractor. “I’m one of them,” he said, “I’ve been there and back.” Sloan El can’t run for office again after pleading guilty, but he’s striving, he said, “to teach young people to get involved politically.”

He dedicates this effort to his old friend Fulbrook, and is passionate about using nonpartisan elections to empower the Camden electorate.

“When I explain to people signing the petition, they get it,” he said. “Now it’s your turn, I tell them, to control the mayor and City Council … they can pick a champion, we’re going to pick our champion, and we can duke it out!”

Rutgers public policy professor and blogger Stephen Danley believes that if the question appears on the ballot this year or next, activists will face the task of convincing residents that nonpartisan elections could make a difference in their lives.

“The Camden population,” said Danley, “is used to being disenfranchised, so there’s a high bar to show that new efforts would result in them getting their rights back.”

Danley thinks nonpartisan elections would give a leg up to grassroots candidates, opening up what has been a daunting political landscape.

“The biggest mystery in Camden,” Danley said, “is what Camden politics would look like if there wasn’t a ballot advantage for Democratic machine incumbents… It’s not clear that challengers have a ready-built coalition to take advantage of the change. But there’s no way to know until there’s a level playing field.”

On Aug. 8, Sloan El and Vance Bowman set up a folding table next to Tony’s Liquors on a run-down block of Mount Ephraim Avenue, and were exhorting passersby to sign the petitions.

“What this does is stop them from controlling our City Council and the mayor,” Bowman told one. “It will make them hear you and listen to you.”

Former Camden Mayor Gwen Faison, now 95, believes that she would not have been elected in a partisan election.

“I wasn’t recognized by my own party,” she said, “but I won, anyway … it was the good people who wanted to help others that helped me.”

A few blocks away in his Parkside neighborhood, Theo Spencer was soliciting signatures door-to-door when he arrived at the home of Nataliece Moore, who was his eighth-grade science teacher.

Moore signed the petition.

“The machine has always been an integral part of Camden’s history,” she said. As a result, Moore believes that many in the city have a “political malaise of not caring” and a belief that “it ain’t going to change, they’ve got it locked up.” It’s her history as a Black American, she said, that makes it impossible for her to succumb to apathy.

“I’m voting,” said Moore, “because there’s been too many people hung from trees for me not to vote.”

Editor’s Note: This story has been updated to remove a quote that identified Gwen Faison as Camden’s first Black mayor. The city’s first Black mayor was Melvin “Randy” Primas Jr.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.