Pennsylvania fiscal watchdog’s municipal pension fix: what it means

Listen 1:34

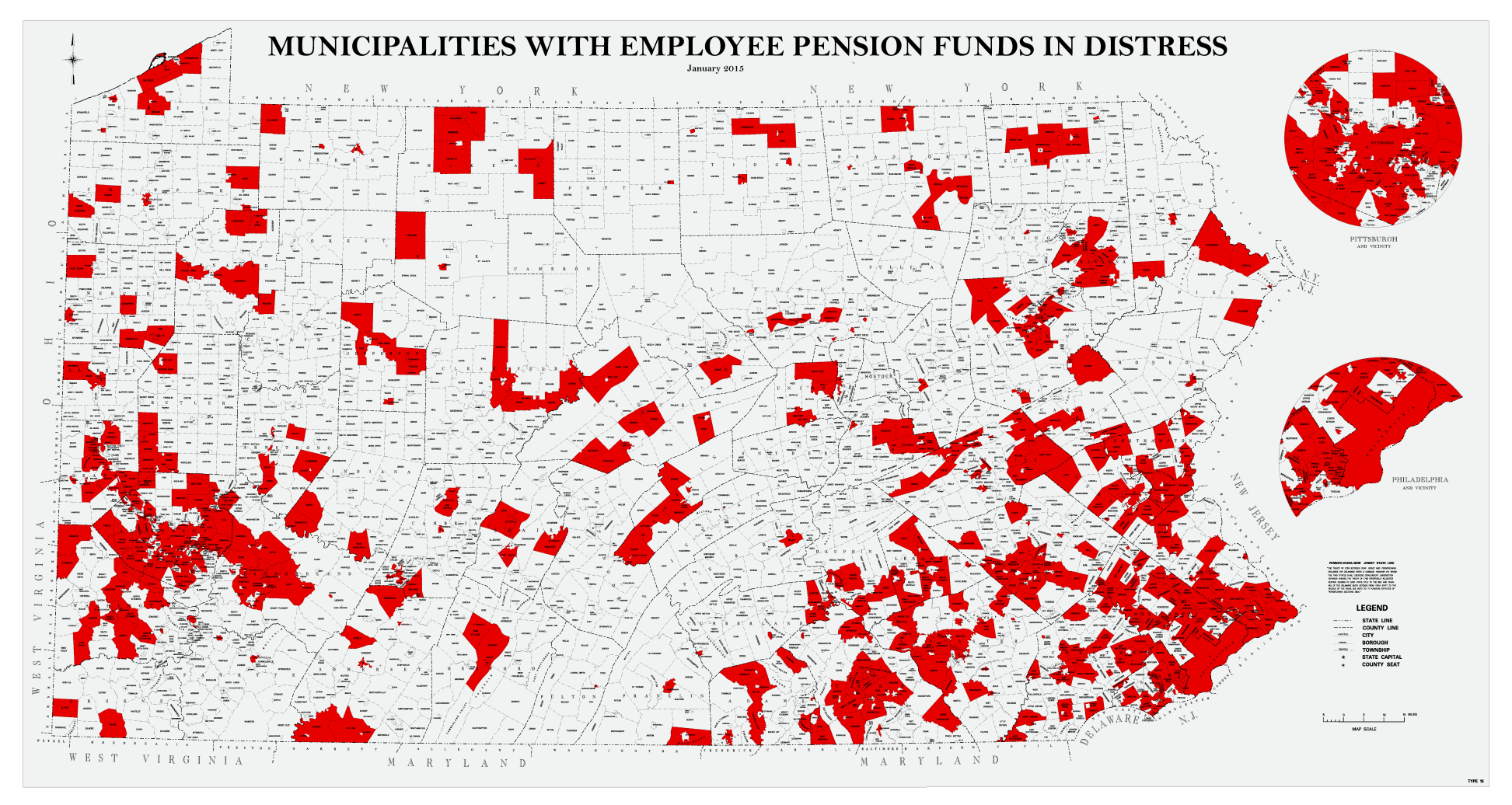

Pennsylvania's municipal pensions were running a $7.7 billion combined deficit last year. (map courtesy Auditor General's office)

Pennsylvania’s local public worker retirement funds have a combined deficit of $7.7 billion. A few years ago, it was $7.2 billion. It went as low as $1 billion in the interim.

The figures fluctuate, but are consistently big enough to indicate the Commonwealth’s municipal pension funds won’t have enough money to pay retirees what’s been promised. That means increased taxes, scaled-back services, or both of those things– possibly in combination with bankruptcy, says state Auditor General Eugene DePasquale. “We saw what happened in Detroit: retirees getting 10 cents on the dollars – basically, getting screwed. Because leaders in Michigan didn’t do it. We have a chance to tackle this in a better way in Pennsylvania,” DePasquale says.

DePasquale, whose office recently released an updated pension shortfall analysis and recommendations, says lawmakers need to act now to avoid a crisis later. “That is not just a Philadelphia issue, and it’s not just a Pittsburgh issue. You’re talking a significant chunk of the Pennsylvania population is in an area that has a distressed municipal pension plan,” DePasquale says.

Potential solution: a statewide system

As many as 1,100 of the state’s local pension funds are distressed, depending on how you define it. DePasquale says one change should be to manage the Commonwealth’s 3,200 municipal pensions in one statewide system. That would help cut administrative costs and foster responsible forecasting and investment practices, he says. The singular fund would maintain defined benefits, and distinct classes for different types of workers and solvent versus insolvent plans. DePasquale also says current employees and new hires alike should be funneled into the consolidated fund.

Franklin & Marshall College’s Center for Politics & Public Affairs Director Terry Madonna says that last part might not stand up to a legal challenge. “The problem becomes when you get into the business of changing current or retired workers pensions, you risk running afoul of the Pennsylvania constitution,” Madonna says.

Cities already have cut benefits retirees already were receiving, not to mention reducing promised future pension payments to current employees. That’s typically happened in bankruptcy court, though, where judges often relax contractual obligations. But underfunded pensions are a problem nationwide, so some financial experts and government officials are trying to rewrite promised retirement benefits for current workers.And momentum is strong for a change, Madonna says. “There’s a growing consensus that these municipal and other plans, just aren’t fiscally sound, and there’s been a growing movement to try to consolidate them,” Madonna says.

DePasquale says his recommendations should curb some of the risk associated with defined benefit plans’ dependency on actuarial forecasts that make assumptions about inflation, wage growth, worker turnover and longevity – and investment returns. Often, these funding shortfalls are a function of over-zealous investment return expectations. Those estimates determine what public employees need to pay into their pensions while they’re still working to get what’s been promised them during their retirement. So when the actual investment returns are lower than projected, the shortfall is compounded.

DePasquale also says cities should insist on actuaries and investment advisors using lower rates, and base payment on performance (or lack thereof). DePasquale, who’s a Democrat, says his next step is meeting individually with members of the Republican-dominated state legislature.

The politics, the proposals

Madonna says DePasquale’s proposal attempts political balance. Democrats typically won’t support a transition to defined contribution plans, like a 401(k). That’s traditionally what Republicans want because employers – in this case, local governments funded by taxpayers – commit only to what they can pay presently. They’re not taking on the risk associated defined benefits’ plans promised payments decades before they’re actually made to retired public workers.

But Republicans in Harrisburg have seemed reluctant to support even a hybrid plan, which would combine the two types, Madonna says. Madonna’s assessment is based on their reception of a hybrid plan for the state system of which they’re a part.

Some legislators already are working on municipal pension bills, at least one of which proposes a hybrid plan. Seth Grove, a York County Republican entering his fourth term in office, plans to reintroduce a tweaked version of his bill. Grove is advocating a statewide pension fund for local police and paid firefighters that would, as DePasquale suggests, incorporate current and future hires. It mandates conservative investment assumptions and guarantees 30 percent below Pennsylvania’s present norm, diverts additional investment earnings to unfunded liabilities of “old” pension funds and prohibits employers from pleding post-retirement healthcare.

Public safety personnel also must have 25 years of service and be older than 55 before they can retire and start collecting. While working, they’d kick in 6 percent – or 9 percent if not participating in Social Security – of their salary into an investment fund. Employers would contribute 4.5 percent. Investment earnings projections would use rates based on Moody’s indexed bond yields of no more than 4.5 percent. That’s two percentage points lower than the current median rate used by the state’s municipal pension plans, according to the most recent Public Employee Retirement Commission report.

Grove’s bill also calls for a 12-year vesting period and payouts that begin before age 71. These changes wouldn’t affect disability, survivor benefits or workers compensation benefits, according to the legislation. Grove and DePasquale stress the statewide system makes pensions portable, meaning workers can move without fear of losing their retirement benefits.

Democratic Rep. Kevin Schreiber, also from York, says he’s working on his own proposal, but isn’t yet ready to discuss details.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.