Leftover painkillers driving opioid crisis, Penn researcher says

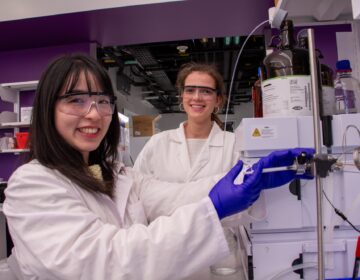

A panel of professors at the University of Pennsylvania discuss the opioid addiction epidemic. They are (from left) dental surgeon Elliot Hersh, psychiatrist Kyle Kampman, registered nurse Peggy Compton, chemist Jeffrey Saven and veterinarian Mary Robinson. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

A researcher at the University of Pennsylvania says one of the big narratives explaining the onset of the opioid crisis is wrong.

Peggy Compton, a professor at Penn’s School of Nursing, said the public often misunderstands the role opioid prescriptions have played in the crisis. The epidemic wasn’t caused by people taking pills prescribed by their doctor to treat pain, she said. That idea, she said during a discussion among pain researchers at Penn, is a “myth.”

“Simply by giving prescribed opioids to patients with pain, we are not creating addicts,” Compton said Friday.

The real problem, she said, is that leftover pills are much more accessible to people who are looking to misuse them. They became more abundantly available when doctors started becoming more “liberal” about prescribing them in the 1990s, she said. People could get them from friends or relatives — or buy them on the street.

“Prescription opioids are easier to obtain in our society than they’ve ever been in history,” Compton said.

About 10 percent of patients who take the pills for chronic pain do become addicted to them, Compton said, but those may be the same people who are prone to addiction in general. Ten percent is also the proportion of the general population will develop some kind of addiction in their lifetime, she said, whether to opioids, alcohol, or some other drug.

“It’s not the drug itself interacting with the brain that’s causing addiction,” she said. “It’s the drug interacting with a vulnerable brain” that leads to addiction.

Another Penn researcher talked about a possible strategy to reduce the number of unused opioids in circulation. Many communities now have “takeback” programs where people can safely dispose of their leftover pills. Elliot V. Hersh, a professor in the dental school, said that a study he conducted found that oral surgery patients are twice as likely to give back their unused pills if they’re given a financial reward of just 25 cents a pill.

“It’s probably something that should be looked at in the future as far as a way to get unused opioids out of the medicine cabinets, because they unfortunately end up on the streets,” Hersh said.

Hersh said research also shows that the class of non-addictive drugs that includes ibuprofen are more effective for pain after dental surgery than opioid pills are, and is trying to convince more oral surgeons to use them as the first-line treatment.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.