Penn Museum opens new Middle East gallery

The Penn Museum has greatly expanded its Middle East gallery, the first part of a building-wide renovation.

-

Lion’s head sculpture from Ur, 2450 BCE. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Jewelry and ornaments found at an excavated home in Tepe Gawra, modern day Iraq, 4300 BCE. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

A bowl made of obsidian (volcanic glass) found at an excavated home in Tepe Gawra, modern day Iraq, 4300 BCE. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

A clay pot made to look like a woven basket found at an excavated home in Tepe Gawra, modern day Iraq, 4300 BCE. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Archaeologists call the amulets “eye idols” and they’re found all over Syria and Iraq. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Arrowheads at the Penn Museum’s Middle East Galleries. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

A Penn Museum curator and a visitor discuss the writing on a bowl in the Middle East Galleries. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Bowls with incantations written in Aramaic were buried near doorways to trap evil spirits. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Lion sculptures were often placed in front of doorways. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Predictions were made based on the reading of lungs of sacrificed sheep and goats. A lung model made of clay was a guide to making predictions. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

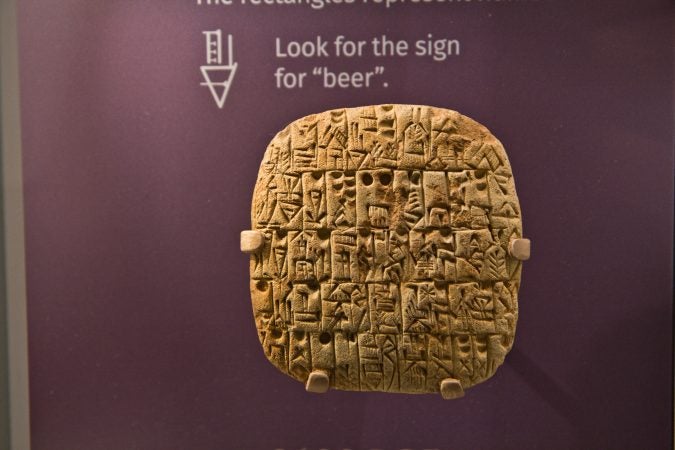

A ledger of clay at the Penn Museum’s Middle East Galleries. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Goat head made of copper alloy, shell and stone, 2475-2300 BCE. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Part Parthian slipper coffin made of a clay. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Figures would sometimes indicate a social status. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Jane Hickman, an expedition editor, explains to visitors how wealthy Queen Puabi was to have been buried in so much jewelry. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Gold and silver bowls found in the death pit. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

A standing goat offering figure at the Penn Museum’s Middle East Galleries. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

The crushed skull and helmet of a young solider who was killed by a blow to the head. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

The crushed skull of a young woman who was killed by a blow to the head. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

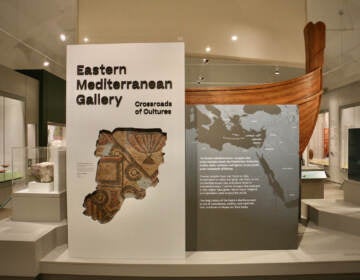

The new Middle East Galleries at the Penn Museum. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

About 7,000 years ago, people living between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers — the general area of what is now Iran and Iraq — started in small farming villages but developed into cities by embracing a most modern adage: Greed is good.

“One of the phenomena of cities is that as more and more people collect there, they become greater and great concentrators of wealth,” said Steve Tinney, deputy director of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

“That means people in power in cities can leverage more materials and more resources to acquire more wealth. Something like that happened in Ur in the mid-3rd millennium BCE, when it became one of the pre-eminent cities of the ancient world,” he said.

Tinney is the coordinating curator of the Penn Museum’s newly renovated Middle East gallery, three times larger than the old one. The new gallery has a new curatorial vision: “Journey to the City,” telling the archaeological story of how mankind developed systems of trade, government, religion, and urban infrastructure in ancient Mesopotamia.

The exhibition is permanent — not by archaeological standards, but by history museum standards: about 25 years. It is based on 1,200 objects selected from the museum’s vast collection of Sumerian artifacts, much of it excavated in the 1930s by Sir Leonard Woolley.

The expansion is the first phase of a multipart, multiyear overhaul of the entire Penn Museum building, which has no central air system. And navigating the hall of a museum that opened in 1899 can be difficult.

“When we were thinking strategically about the future of the museum, we knew we had to display our collections from the Middle East in a way that did them justice,” said Tinney. “We have such vast collections, and they are so important worldwide to the story of cities and the story of civilization, that we decided to put them first on the list, to make them the first gallery redo of our long-term plans.”

The exhibition displays the groundwork for what would become the modern city: education systems in the form of clay tablets for students to practice cuneiform figures; trade agreements in the form of seals denoting partnerships; a labor force employed in mass production implied by bowls calibrated for rations; and evidence of ambition to organize large swaths of people and resources in a way that creates power.

“One of the things that is happening here is that it’s not just individual cities are organizing themselves, but groups of cities are organizing themselves into larger units, which we don’t quite understand yet,” said Tinney.

The artifacts are wonderful to look at. The development of sophisticated ceramics, using oxygen-reduction firing techniques, produced beautifully ashen pottery. The region of Ur was not particularly rich in natural resources, but had great pastures for raising sheep; its main export was textiles, which were traded all over the Middle and Far East.

The exhibition includes the tools of trades, including a merchant’s scale.

“There are a couple series of weights, including my favorite, a collection of duck weights,” said Tinney. “It was common in Sumeria to make weights in the form of resting ducks with their heads resting on their backs. They are made in a great range of sizes, from a few grams to several pounds.”

The centerpiece of the museum’s Middle East collection is the extravagant burial jewelry of Queen Puabi, who ruled Ur in 2600 BCE. The ornate headpiece and draped necklaces, which adorned her corpse, were found several thousand years later completely intact.

“When she was buried, Queen Puabi was really wearing the known world in her jewelry, with carnelian from India, lapis from the highlands of Iran, gold from Iran and Turkey,” said Tinny.

Puabi was not just buried with jewelry, but her entire entourage. A few feet away is a display of a royal tomb, called the Great Death Pit, wherein over 70 bodies were found in an arrangement of an afterlife banquet.

It’s likely they did not go gently.

“We think it’s quite possible that people in the banquet were killed, then partially preserved by baking, then situated in their positions in the banquet to construct a scene which would have been the scene of the priestess’ arrival in the underworld,” said Tinney.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.