Parents spar angrily with founder of closing charter school in N.E. Philly

Listen

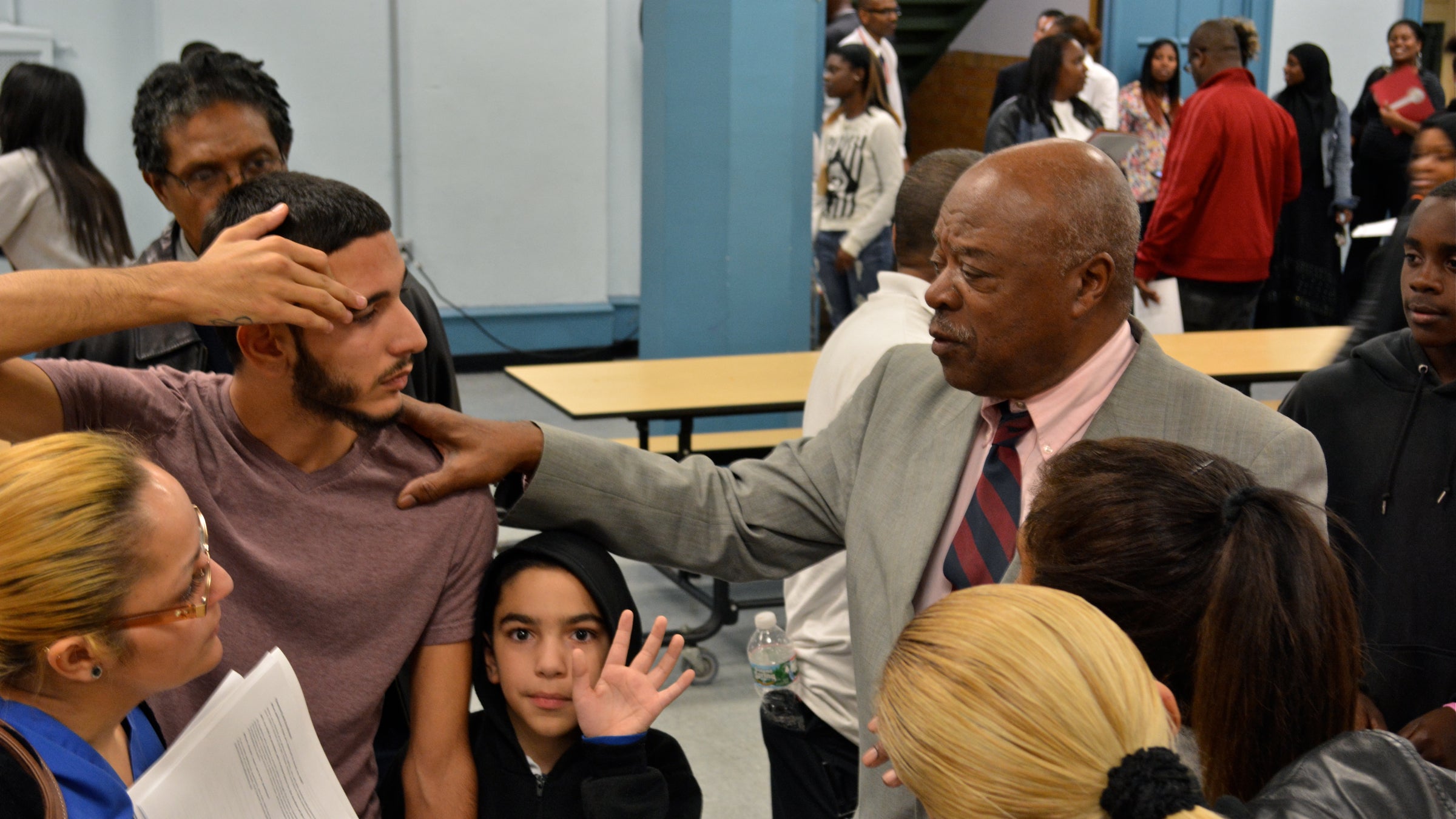

Walter Palmer (right) consoles a student who suddenly finds himself without a school. The embattled Walter D. Palmer Leadership Learning Partners Charter closed its high school and halved its elementary enrollment two months into the school year. (Kevin McCorry/WHYY)

Sparks flew at a meeting for parents at Walter D. Palmer Leadership Learning Partners Charter charter high school Monday night. The school’s basement cafeteria became a battleground between the school’s founder and a throng of incensed parents.

Many had learned only that morning that the high school program at the school’s Wissinoming campus was permanently closing and that their children would have to find another school two months into the year.

“I’m frustrated with Walter Palmer. I’m frustrated with the district. I’m frustrated with everybody,” said parent Courtney Dennis.

The Palmer charter school and the Philadelphia school district have been embroiled in a legal dispute for years over exactly how many students the charter should be allowed to enroll. Last May, the State Supreme Court sided with the district, saying that Palmer needed to abide by an agreement it signed in 2005 which capped enrollment at 675 kids.

Despite that ruling, Palmer opened its doors this year with close to 1,300 students knowing that – barring a legal “Hail Mary pass” – it would only get funding for 675.

The pain of that decision really began to sink in over the past few days as parents learned the high school would close – leaving 286 students in a nightmarish scramble to find another school.

Last spring, after the Supreme Court ruled, Dennis says Palmer officials convinced her that it was still a good idea to send her kid to Palmer’s high school campus on Harbison Avenue.

“But my thing is why would you accept all these kids, enroll all these kids, and you know you wasn’t funding all these kids?” she asked. “This is horrible.”

Last week, Palmer held a lottery to whittle 250 students out of his Northern Liberties elementary school. In total, more than 500 Palmer students have been displaced from their school.

Walter Palmer began the night’s formal proceedings by giving a history of the school’s early successes attracting parents while sprinkling in bits of his own autobiography as a civil-rights activist.

“A lot of them had heard about the work we’d done in the 1950s and 1960s working with black and Hispanic children – at risk children, which has really been my driving force for the past 60 years,” said Palmer.

Palmer then introduced a slate of representatives from other schools: district, cyber charter and parochial, explaining that his team would help parents through the transition.

“People are saying, ‘What’s going to happen? You’re throwing them out.’ No, we’re not,” Palmer said through a crackling speaker. “We’re going to work with our children until we transition them. We’re going to follow them, even though they may not be on our books.”

Fervor builds

The audience listened quietly for more than 10 minutes, but then, as Palmer attempted to introduce some of the senior class to speak glowingly about their experience at the school, the crowd grew restless with how the meeting was going.

Soon, the evening’s planned agenda was overrun by the shouts of angry parents.

Rashida Jabbar grew teary eyed shouting to Palmer from across the room about her grandson.

“I trusted them,” she cried. “They’re just throwing him to the wolves. And the only thing this man came here to do is talk about his life. We’ve done heard that story already. We don’t want to hear nothing about his life. What about their lives?”

“He’s a thief!” scolded Jeanie Marks, grandmother of a Palmer 9th grader.

For many parents in the crowd, the frustrations were threefold:

The city’s other charter schools aren’t taking new kids.

Catholic school tuition is more than many say they can afford.

The district’s neighborhood schools – which will accept anyone at anytime – are their least preferred option.

For Lissetta Villanueva, whose son is in 10th grade, the neighborhood school would be Kensington.

“Uh-uh. Not at all. Not Kensington,” she said. “Not at all. So now we got to go search and see what schools will take him, knowing that charter schools are full. ‘Cause they’re full. I’ve been searching.”

Other options

School district officials attended the session to inform parents about all district options, including vacancies in some sought-after specialty admission programs.

West Philadelphia High Principal Mary Dean told parents that her school could accommodate all 286 displaced students, if they so chose.

A slate of the city’s archdiocesan schools set up tables around the perimeter of the room, as did a few of the state’s cyber charters.

“We are providing $1,000 for anyone who wants to come to our school,” said Father Joe Campellone, school president at Father Judge High School, which costs roughly $7,000 per year. “And then we’ll sit down and talk to them if they’d like to apply for any type of financial aid.”

Toni Kauffman, director of community relations for PA Virtual Charter School, drew many parents to her table with her “tuition-free” pitch.

“These poor parents are feeling very desperate to find the right placement for their children to ensure that they get an education,” said Kauffman.

Ya’ll got to leave

As the ire grew around Palmer, his staffers began yelling at media to leave the property, even though Palmer’s hired PR firm had invited reporters to the event.

“Yo, ya’ll got to leave,” said the staffer. “Ya’ll got to leave.”

Inflamed by the the staffer’s request, parents rallied to the defense of the swarm of reporters and cameramen around Palmer.

“He ain’t leaving. Oh, we’re going to stay here and watch him,” Rashida Jabbar said about one reporter. “We’re going to protect him.”

In the end, no one was kicked out.

Despite his handlers’ insistence, Palmer answered all reporters’ questions and engaged with every parent who wished to speak with him.

He disagreed, though, with parents who felt he misled them by continuing to enroll students above the cap.

“Everybody has known about the fight, and we’ve warned people that at some point has got to come to a head, and finally we ran out of our legal options last month,” said Palmer.

Earlier in the evening, parent Paul Kirby complained that Palmer’s staff have been stonewalling his weeks-long attempt to transfer his 14-year-old daughter, Ashley, into Frankford High school.

“It’s been crazy. Walter Palmer wouldn’t let her go,” he said. “I’m just frustrated.”

When asked about Kirby’s situation – one similar to complaints heard from other Palmer parents over the years – Palmer disputed the notion that his staff would prevent parents from withdrawing thier students.

“There’d be no reason. There’d be no benefit,” he said. “The reality is we’re forced to come into a K-8 configuration. What would be the benefit?”

The Philadelphia School District alleges that Palmer has stalled on the transfer process over the years to retain the funding that would be lost if students left.

Palmer denied that charge and said complaints against his school have been “blown out of proportion.”

“That’s why I said to some of the parents, ‘Don’t let this be your grandiose moment,'” he told reporters, ‘”because when these lights shut down, the cameras are off and the radio stops, they won’t be here for you.

“I will. I always am. I always have been. I spent 60 years of my life being there.”

The 675 students who remain in Palmer’s elementary school may soon have to find a new school as well.

For a host of reasons, including paltry test scores and questionable financials, the School Reform Commission has been in the process of revoking Palmer’s charter agreement. Palmer is appealing the decision and hopes his school will continue.

District Superintendent William Hite has promised that Palmer charter will remain open until through the 2014-15 school year.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.