Paper chase: Fearing hacked election, Pa. officials scramble ahead of 2020 to bolster security

While there is no case of results being tampered with in Pennsylvania, reports of Russian interference in 2016 have raised concerns that the digital totals could be hacked.

Duquesne University students wait to cast their votes in Pittsburgh during the 2016 Election. (AP Photo/Gene J. Puskar)

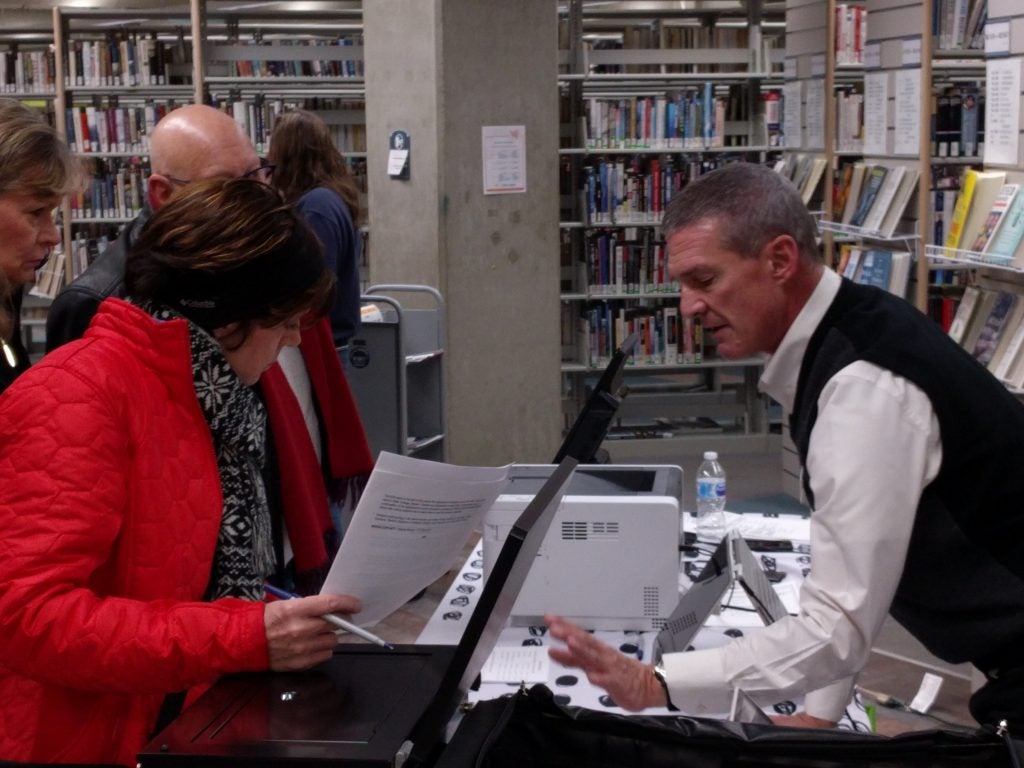

A bitter cold snap in Erie last week didn’t keep away scores of people from visiting the city’s lakeside library last week, checking out the next generation in voting machines as county officials from across the state scramble with a new voting security mandate.

Many, like Joe Gallagher, were poll workers who could be using the machines a little more than a year from now.

Gallagher said he came out of “curiosity about the integrity of systems we’re putting into place. There are always some windows open for error.”

Pennsylvania plans to close at least one of those windows, replacing every voting machine used in the state with machines that retain a paper record.

The path toward doing so won’t be straightforward, as the range of machines on display suggested.

Some vendors, like Russ Dawson of Electec Election Services, boasted of how low-tech their systems are.

While other firms have every voter mark their ballot with a touchscreen, Dawson said, “In our case, this is the ballot marking device: a pen.”

You don’t even need to color in the entire oval on the ballot, he said. The ballots are then scanned into a device which, like many others, looks like a fax machine grafted to a garbage can where ballots are stored.

Not far away stood Joe Passarella of Election Systems & Software, whose company makes the digital iVotronic machines now used in Allegheny and many other counties. But the new ES&S models also produce a paper ballot, using a familiar touch-screen, to be scanned.

“It’s gonna print your selection on that card,” he explained.“It’s gonna return it to you, so then you get the opportunity to physically look at your ballot printed out.”

The idea is that after Election Night, poll workers can physically examine the ballot too, to verify the machine recorded correctly.

While there is no case of a machine’s results being tampered with in Pennsylvania, reports of Russian interference in the 2016 election have raised concerns that the digital totals could be hacked.

Last year, Gov. Tom Wolf’s administration issued a requirement that by 2020, all state voting machines must have a paper trail. Counties need to buy machines approved at both the state and federal level. That policy was codified in a legal settlement reached with the Green Party in a lawsuit stemming from the 2016 election.

Unfunded mandate?

How much will this all cost? Passarella, whose firm was displaying three separate voting systems at the open house, chuckled when asked.

“We’ll quote the county” a price, he said. “It’s difficult to gauge how many they’re going to need in each precinct and everything else.”

Other vendors offered ballpark costs that mostly ranged in the middle four-digit range. And even counties that already use paper ballots will have to buy new equipment.

The state’s election commissioner, Jonathan Marks, said that statewide, the new machines will cost at least $100 million.

“The state, federal and counties all have to work together to fund this so that the counties aren’t bearing the entire cost,” Marks said. “The governor is very committed to secure at least 50 percent of the funding it would take to procure this voting equipment.”

Even coming up with half of that money won’t be easy, says Douglas Hill, who heads an organization that represents county leaders across the state.

“This is an expense that wasn’t anticipated, and it’s fairly sizable compared to a county budget,” he said. “We appreciate that the government will be proposing to fund at least half of that, but we hope to get it even higher than that.”

They’ve got a long way to go. Wolf has about $15 million in federal money on hand, and the 2019-2020 budget proposal he offered earlier this week requests $15 million more for the upgrades.

But there are no guarantees he’ll get that money. State Republican Party Chairman Val DiGiorgio seemed unimpressed by Wolf’s pitch.

“I don’t know the governor has made the case as to why we need a wholesale change in voting machines,” he said. “It’s to fit into this narrative that somehow the 2016 election was not valid.”

Deadline looms

Meanwhile, the 2020 elections are rapidly approaching and the logistical implications of this mandate are far reaching.

Allegheny County, for one, spent months training poll workers and others the last time it bought machines for its 1,300 polling places. County spokeswoman Amie Downs says officials know they’re up against a deadline, but they don’t know when they’ll make a purchase.

“We don’t have a set time frame, and I think a lot of it has to do with what the funding’s going to look like,” she said. “But we are absolutely 100 percent aware of the challenges of even just training the public.”

Few election officials want to unveil a new voting system in a presidential year, when turnout – and scrutiny – are greatest. But some fear they have little choice.

“I think we’re more likely to debut [the new machines] in 2020,” said Doug Smith, Erie County’s clerk of elections. It’s too late to buy new machines for the 2019 primary, and “rolling out two systems in one year is pretty tough.”

Unlike Erie, Allegheny County hasn’t hosted its own open-house on voting machines. Downs says the state is still approving some machines for county use, and officials want voters to have a chance to see them all.

But Marybeth Kuznik, who heads the statewide voting-reform group VotePA, is worried the some of the new machines still rely too much on digital technology, especially to mark ballots.

“What we’re really concerned about is that all but one of them count using either a bar code or a QR code,” she said. “The machine takes the voters choices from the touch screen and interprets that into a bar code. It counts using the barcode, so there’s no way that the voter can be certain the bar code matches the words that he or she saw on their paper.”

Activists, many of whom were dubious about counties’ decisions to buy paperless systems in the first place, also fear the influence of vendors.

A Luzerne County official drew fire last year for accepting trips from ES&S in her capacity as an advisory board member. Auditor General Eugene DePasquale launched a review of such practices in the state, and his office says that work is ongoing.

But despite those misgivings, Kuznik said it was “absolutely wonderful that the governor decided to go with paper ballots, and that we have paper protecting our elections.”

Erie Judge of Elections Michael Butler is optimistic about the future after reviewing the machines at the open house.

Voters in his district struggled to use the touch-screens a decade ago, he said. This time, though, “I think it will be easier for them. We’re using paper [as backup], and I never thought we’d go back to that. But some of the machines that they’re using are doing a real good job.”

Butler and others at the Erie event got to vote in a survey of their favorite system. County officials haven’t yet determined a winner. But whatever the outcome, there will be a paper trail.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.