Pa. school districts make an ‘educated guess’ of next year’s budget

Many districts report that they will raise taxes and cut staff and programs to meet rising state-mandated costs. (Source: The PASA-PASBO Report on School District Budgets)

Making a budget before knowing how much money you have might seem like putting the cart before the horse. But that’s exactly what many school districts in Pennsylvania are doing.

The state budget is technically due June 30, but Gov. Tom Wolf stated publicly as early as April that the state might not meet that deadline. By law, school districts must adopt their budgets by the end of the month.

In its fifth annual survey of school districts, the Pennsylvania Association of School Administrators (PASA) and the Pennsylvania Association of School Business Officials (PASBO) rounded up stories of how school leaders are planning around budget uncertainty.

In all, 346 districts, from 66 of the state’s 67 counties, responded. Of those districts, 71 percent said they’re raising property taxes this year. Eighty percent are taxing at or above their Act 1 limit, a cap the state created to keep property taxes in check.

Forty-one percent of districts said they’re also planning to cut staff next year.

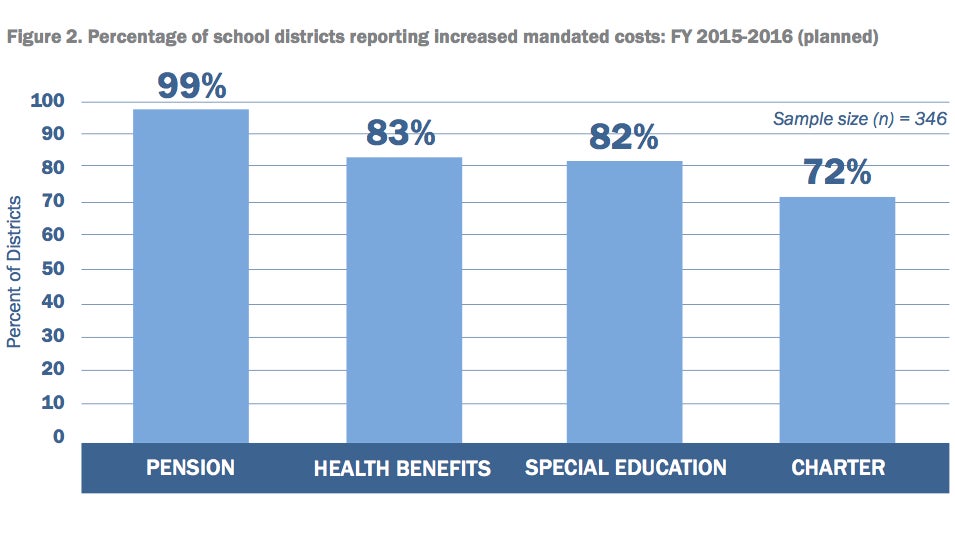

The culprits, according to PASA’s executive director Jim Buckheit, are state-mandated costs, such as pensions, benefits and payments to charter schools.

“Even with raising property taxes, cutting staff, reducing programing, the external cost drivers… continue to drive the budget to the point that many districts are facing deficits,” said Buckheit.

Penn State education professor William Hartman also looks at the impact of financial policy and rising costs on Pennsylvania school districts. He said the cutbacks on staff and programs are a continuation of a trend.

“They have been doing this since 2012, the problem is [the deficit] doesn’t go away,” said Hartman.

Hartman, in conjunction with Temple University’s Center on Regional Politics, found that in the next five years more than half of all school districts in Pennsylvania would not be making ends meet. Schools have to follow state law and pay increasing amounts for employee pensions, so they end up cutting back to try to balance their books, said Hartman.

Not having enough money to operate, he said, “Is not a hypothetical situation for districts. It’s a very real one.”

Pa. one of the most unequal states in terms of education funding

The lack of a predictable, student-weighted formula and the relatively small contribution by the state toward public education drives greater inequality in Pennsylvania compared to many states.

“Everybody’s facing the same budgetary pressures, but some districts have the capacity in their community to deal with those increases,” said Buckheit. Districts with lower fund balances and less property tax revenue tend to cut back the most.

As of last week, a bipartisan state commission shared its recommendation for a fair funding formula. It takes into account a number of factors that may increase education costs by district, including the number of students in poverty and charter school costs. It does not create a benchmark for adequacy, or how much money districts should have to educate their students. The legislature and the governor will have to approve the formula for it to take effect.

Also on the table is Gov. Wolf’s proposed education budget increase, which aims to restore cuts that began in 2011 with the loss of federal stimulus money.

According to the PASA/PASBO survey, 43 percent of the districts said that they could minimize any staff reductions and also reduce property taxes if Wolf’s budget is approved.

That money would help with the funding side, but what about the expenditures?”There’s I think a misconception that once the pension prices peak, the pension crisis is gone,” said Hartman. “It doesn’t go away.”

While the yearly increases to how much districts have to pay towards state-run employee pensions have slowed down, the total amount still tripled in the last five years.

So even with a funding formula and more money on the table, as well as legislators pushing pension reform, school districts still know more about their costs for next year than about how much money they’ll be getting.

Making a budget, “It’s really just an educated guess on their part,” said Hartman. He said based on survey results, some are banking on a small increase in state funding, some on a large increase, and some on no change at all.

Disclosure: The William Penn Foundation contributed funds to the PASA/PASBO report and is also a supporter of WHYY.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.