Chester County Intermediate Unit settles case alleging abuse at Glen Mills Schools

The agreement establishes two separate funds — one for students’ ongoing education needs and another for damages.

A sign stands outside the Glen Mills Schools in Glen Mills, Pa., Thursday, March 7, 2019. (Matt Rourke/AP Photo)

Got a question about life in Philly’s suburbs? Our suburban reporters want to hear from you! Ask us a question or send an idea for a story you think we should cover.

Hundreds of students who suffered abuse at a once celebrated boys reform school outside of Philadelphia will share a $3 million settlement, their lawyers said Wednesday.

The agreement, between students who recently attended Glen Mills Schools in Delaware County and the school’s local educational agency Chester County Intermediate Unit, establishes two separate funds — one for students’ ongoing education needs and another for damages.

In a written statement to WHYY News, Chester County Intermediary Unit Executive Director George F. Fiore said settling the case “was in the best interest” of the former students.

“The case was entering its fourth year. Continuing to litigate and drag the case out for years was not beneficial to anyone, especially the former Glen Mills School students. We strongly believe that future legal expenses are better directed to serving and improving the lives of former GMS students and not in continuing litigation. It is our sincere hope that the settlement funds will begin to help improve the lives of the former Glen Mills students,” Fiore said.

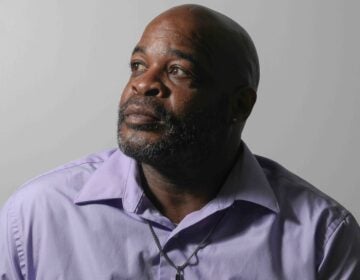

Sergio Hyland, 41, attended Glen Mills in the mid-90s. He is ineligible for the settlement, but he said for those it will benefit, the money is simply not enough.

“As a person who experienced the abuse, the news is saddening, actually. $3 million is almost nothing compared to what children were subjected to, in a school where they were supposed to be protected,” Hyland said.

Maura McInerney, legal director at the Education Law Center (ELC), one of several organizations representing students and families, said the settlement with just one of several defendants is a starting place.

“It is definitely not sufficient,” McInerney said on a call with reporters Thursday. “The Pennsylvania Department of Education also bears responsibility with regard to the failure to educate children in this juvenile justice facility.”

The ELC, Juvenile Law Center, and the private law firm Dechert LLP filed a class action lawsuit on behalf of students in 2019. Shortly after, the state revoked the school’s license for “gross incompetence, negligence, and misconduct,” and “mistreatment and abuse of children in care.”

Reporting from The Philadelphia Inquirer, which found counselors regularly beat students for minor misconduct and threatened them to stay quiet, kicked off the process.

In addition to physical and emotional abuse, the lawsuit also claims that the school violated students’ education rights.

“Students were offered nothing more than a GED book or required to sit quietly in front of a computer in a self-directed limited credit recovery program while the hope of a meaningful high school diploma slipped away,” the lawsuit says.

McInerney said her team will continue to pursue charges against the lawsuit’s other defendants, which include employees of Glen Mills Schools, and officials with the state’s Departments of Human Services and Education.

The lawsuit is in the discovery phase and a trial date has not been set, McInerney said.

Attorney for the former Glen Mills Schools Joe McHale said in a written statement that the well-being of the school’s former students remains “of paramount concern” and that it would be “inappropriate” to comment since litigation is ongoing.

Spokespeople for Pennsylvania’s Departments of Human Services and Education said in separate emails that the departments do not comment on ongoing litigation.

Boys from across the country were sent to the school by court order for nearly two centuries and the school made more than $40 million in annual revenue. Philadelphia, which accounted for about 40% of Glen Mills students, paid $52,000 a year for each boy it sent to the school, the Inquirer reported.

Recent students have one year to apply for relief

Students who attended Glen Mills for any amount of time after April 11, 2017, are eligible for relief, as well as any student who attended earlier and was under the age of 20 when the lawsuit was first filed.

That covers an estimated 1,600 young adults, said Margie Wakelin, senior staff attorney at the ELC. All students who attended school during the settlement’s window are eligible for compensatory education services.

Wakelin said money from the compensatory fund can be used for everything from tutoring, art and music courses, to therapy and mental health services.

Students who “experienced or observed physical abuse or restraint during school hours” can also apply for relief through the damages fund.

Students have until Jan. 19, 2024 to apply for relief from both funds. To apply, students must complete separate forms for each fund that will be available on the settlement’s website.

After the one-year period, those who applied will be told whether they’re eligible and how much money they’ll receive based on how many people come forward, Wakelin said.

“It’s important that it’s happening at this time when students can use [the money] to really change the trajectory of their futures,” McInerny said.

‘Glen Mills destroyed my life’: Former student believes the school should never reopen

Born and raised in Philadelphia, Hyland, the former student, said his stint at Glen Mills was a living nightmare.

“I don’t hesitate when I say this: Glen Mills destroyed my life. Before I went to Glen Mills, I was just a typical child. I engaged in typical mischief,” Hyland said.

Once at the reformatory school, abuse from the staff transformed Hyland into a “cynical” and “violent adolescent,” ultimately pushing him through the school-to-prison pipeline. Hyland was able to put his life together after spending 22 years in state prison.

When news of the decades-long scandal at Glen Mills Schools first broke, Hyland worked tirelessly to get his story of abuse into the public as he searched for accountability.

“A law firm reached out to me and got permission to acquire my records. And they realized that the abuse that I suffered was so egregious, that they had separated me into a group of people who will lead the class, but some brilliant judge decided that the statute of limitations shouldn’t be waived, and people like myself would never see any justice for what happened to us up there,” Hyland said.

Hyland said it’s time to rethink the criminal justice system, especially as it pertains to how youth are treated.

Since 2021, Glen Mills Schools has been trying to reopen under a new name — the Clock Tower Schools. While the state Department of Human Services has since batted down licensure attempts from the new nonprofit, the Clock Tower Schools has not ended its pursuit.

The Clock Tower Schools have insisted there are no ties between them and the shuttered institution. The nonprofit declined to comment on the settlement.

Hyland said the soil where Glen Mills Schools used to operate is poison and anything that rises from it will be just as harmful.

”I don’t care what name they put on the front of the school, it’s going to be hell for anybody who goes there,” Hyland said.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.