Pa. aid society honors young immigrant author for courage, determination

Montco student's 'Dreams and Nightmares' details perilous trek from Guatemala to asylum in U.S. 'It’s the story of all of us who come to this country,' she says.

Liliana Velasquez, 20, fled Guatemala on her own to seek asylum in the United States.

Plastered with poster-size Post-It notes, Liliana Velasquez’s Upper Darby apartment has the air of a classroom.

In the living room are long lists of words with silent consonants, like g in gnaw; b in plumber; k in knack. In the kitchen, verb conjugations. In the bathroom, measurements: 24 hours is a day; seven days is a week.

The in-your-face study aids for her Montgomery County Community College classes are emblematic of the fierce focus of 20-year-old Velasquez, who was 14 when she set off on a solo trek from Guatemala, determined to seek asylum in the United States.

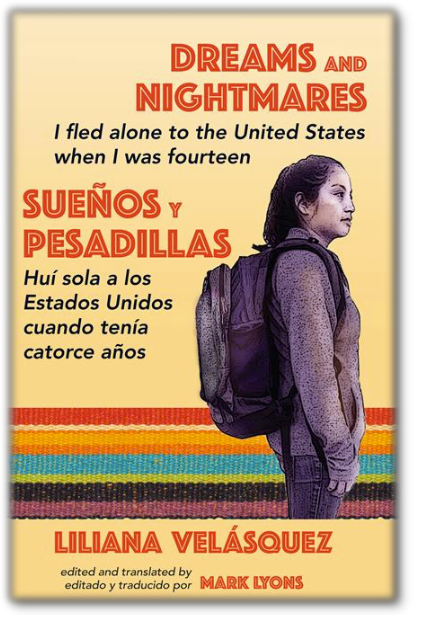

Her book, “Dreams and Nightmares (Suenos y Pesadillas),” published last year and now part of the ESL curricula at many high schools nationally, is a harrowing account of that journey.

“It’s not just my story. It’s the story of all of us who come to this country” fleeing violence and pursuing dreams, she said Sunday.

“It’s not just my story. It’s the story of all of us who come to this country” fleeing violence and pursuing dreams, she said Sunday.

On Tuesday she will receive a Golden Door Award from the immigrant aid society HIAS Pennsylvania.The annual award recognizes individuals “who lead the way in support of immigrants and refugees.”

Of the nerve and determination it takes to flee Central America alone as a teen, she said, her strongest driver was “anger.”

Anger at being ripped from school in the second grade by her bickering parents and made to take on the chores of running the household. They told her she didn’t need an education; the only thing she should prepare for was an early marriage.

Then a boy in her village, where robberies were common, accosted her sexually and tried to force her to be his girlfriend.

Seething, she summoned courage by talking to herself in the mirror, saying, “I don’t care what is going to happen to me. I just want to get out of this place.”

Each year for the past decade, tens of thousands of children have fled lives of poverty and abuse in Central America, heading north, and knowing that their rugged, solitary journeys toward new beginnings in the United States could, instead, be the end for them.

In immigration-speak, they are “UACs,” unaccompanied alien children. To those exasperated by their relentless quest to cross the border, they’ve been a “surge,” a “swarm.”

Focus on Velasquez, who fled the domestic violence of her parents and a destitute hamlet in the Guatemalan mountains in 2013, and you get a clearer picture of what propelled more than 38,000 other children under 18 to make the life-or-death trek to America from Honduras, Guatemala, El Salvador and Mexico that same year.

Dark-haired and petite, Velasquez shared their common experience. She rode atop boxcars across Mexico on the train nicknamed The Beast because its wheels often grind up people who fall off. She fended off sexual assaults, and was robbed at gunpoint by narcos.

HIAS says her story typifies “the myriad challenges that immigrant children fleeing family and/or gang violence in Central America face.”

For three weeks, she walked and hitched rides 2,000 miles through Mexico, surrendered to the U.S. border patrol in Arizona, sought asylum, and was locked up to face deportation.

But what could have gone very wrong for her went unexpectedly right because she was one of the lucky ones whose free legal representation began immediately while she was in detention at a group home in Phoenix.

With the subsequent supports of foster care, pro-bono legal advocacy in Pennsylvania by attorney Jeanne Barnum of Schnader, Harrison, Segal & Lewis, and the emotional support of a Philadelphia nonprofit called La Puerto Abierta (“the open door”), Velasquez graduated from a collaborative program between Lower Merion High School and Central Montco Technical High School, and received a partial scholarship to attend Montgomery County Community College with the ambition to become a nurse.

She pays the remainder of her tuition with honoraria she gets from telling her story at schools. Recently, she was the keynote speaker at a daylong conference on immigration at Friends Seminary in New York City.

“By telling my story,” she says in the book, “I feel at peace, unburdened.”

Her bilingual memoir was published in 2017 by Parlor Press, with editing and translation by local writer Mark Lyons, director of the Philadelphia Storytelling Project, which he founded in 2003 to gather oral histories of immigrants and refugees.

The book’s collar-grabbing introduction plunges readers into Velasquez’s world.

Imagine this: You are nine years old living with your parents and seven brothers and sisters in a one-room, dirt-floored mud house. … Your two older brothers leave to find work in the packing plants of North Carolina, your father’s health fails and he descends into alcoholism. You are pulled out of [school] to take care of the house full time — cooking, cutting and carrying fire wood … hauling water … watching after your four younger siblings and seven goats. The violence between your parents turns on you, beatings with sticks; a scissor through the air leaves a scar in your skull. A man in the village grabs you by the hair and tries to make you his woman. [Desperate] you buy a pair of sneakers, your first shoes … and make escape plans.

“Lily represents most of the kids that we see in terms of determination, tenacity, [and] the struggles, worries and pain they work through,” said family therapist Cathi Tillman, who founded an international coalition for family wellness in 2005 and christened it La Puerta Abierta in 2010. Depending on the time of year, the group has 150 to 200 immigrant children in its counseling programs.

“The difference between Lily and all these others kids,” Tillman said, “is that she wrote a book about it.”

Velasquez recounts how she rode buses and had to hop off to walk around the checkpoints where Mexican federal police demanded papers.

‘The family of my dreams’

She slept outdoors, or found spot jobs washing dishes for room and board. She covered herself with plastic bags to fend off stinging insects. She never knew how much to trust the sometimes drunken coyote who guided her north.

On arriving in the U.S., UACs enter a legal system that has three basic options for them: deportation, asylum, or Special Immigrant Juvenile (SIJ) status if a civil court determines there was abuse or neglect by one or both parents, whose parental rights are then severed.

From Arizona, where she spent four months while counselors investigated her case, Velasquez was sent to Philadelphia because a Lutheran-affiliated resettlement agency here was available to supervise her foster placement while her SIJ application proceeded.

When her first foster placement turned out to be a bad fit, she was placed with a family in Lower Merion that she calls “the family of my dreams.” She eventually gained an SIJ visa and green card for permanent residency.

To help with her adjustment, her foster care case worker led her to La Puerta Abierta, where she met teens with backgrounds like hers.

Lyons, who has a background working with migrants, joined the group and used video to capture the teens’ stories. That’s how he encountered Velasquez, who later asked him for help writing the book. He said he didn’t have to think twice about deciding to help: “In this time when the issue of undocumented immigrants is causing great divisions within our country, much is written about them, but little is told by them in their own voice. [Her] story needs to be part of our national conversation.”

The two met more than 40 times over the next 14 months. At first, they just talked — no writing or recording. Then, biweekly, they recorded parts of her story in Spanish. Lyons transcribed and edited each session. Velasquez annotated the drafts and amplified the narrative. The final product blends her remorse and forgiveness for the family she fled, and appreciation for everyone who has helped her in America.

She says that she has been “blessed to have two families,” even if her biological parents mistreated her.

“My family in Guatemala gave me life,” she said Sunday. “My family here gave me opportunities.”

Also receiving Golden Door awards at the reception in the Crystal Tea Room Tuesday are: Sanford Mozes, a senior partner of the law firm Fox Rothschild, who for 35 years has been a member of the HIAS board and formerly was its president; and the law firm Morgan, Lewis & Bockius, for its pro-bono work helping hundreds of immigrants and refugees to become U.S. citizens.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.