Opioid overdoses sending twice as many kids to hospital

Over a decade, more than 3,600 children were admitted hospitals for opioid ingestion — about 800 between 2004 and 2007 and more than 1,500 between 2012 and 2015.

(Chris Post/AP Photo)

Twice as many kids are going to the hospital for opioid overdoses than 10 years ago, according to a new study by researchers at the University of Chicago and published in the journal Pediatrics.

Over a decade, more than 3,600 children were admitted hospitals for opioid poisoning — about 800 between 2004 and 2007 and more than 1,500 between 2012 and 2015, the researchers found.

Most of the young patients likely used the drugs intentionally — recreationally or intending to hurt themselves. But a surprising proportion — about one third — were between 1 and 6 years old. Researcher Jason Kane attributed their swallowing the pills to “exploratory behavior” — or putting random stuff in their mouths.

While the number of children requiring intensive care in cases involving opioids rose, the fatality rate dropped from 2.8 percent to 1.3 percent during the study period.

“On some level, it may mean that we’re getting better at caring for these children,” said Kane, who led the study out of the University of Chicago. “The field of pediatric care is evolving.”

Children might not be dying from overdoses, but opioids can slow the respiratory system to the point that it cuts off the flow of oxygen to the brain, causing potential long-term damage.

Treatment comes at a cost. On a systems level, the pediatric workforce is in high demand, with many professional shortages throughout the industry. And, Kane pointed out, these are all preventable conditions.

“Every time we put a pediatric patient in a pediatric ICU bed, we’re using a limited commodity,” he said.

On top of that, the care doesn’t pay for itself. Kane found that each treatment cost an average of $5,000, and most of the patients were insured through Medicaid.

“Any reduction in Medicaid funding could have a profound impact on a hospital or hospital system’s ability to recuperate the cost of caring for these patients,” he said.

In 20 percent of the cases involving the 1- to 5-year-olds, methadone was the opiod swallowed, Kane and his colleagues found. With a 560 percent increase in methadone prescriptions nationwide, Kane sees a correlation. He said these prescriptions may not have the types of cautionary messages families are used to when handling medications that could pose a risk to kids.

“Medication safety, prevention safety is not a new topic for pediatricians,” said Kane. “Childproof caps are not new — we teach our families to keep their medications up in high medicine cabinets.”

As the rate of opioid ingestion among children increases, Kane said, it’s striking that trend isn’t mirrored with overdoses of other medications.

“So there’s something about the opioids that’s different, and it might just be reflecting the amount of drug that’s in the community,” he said.

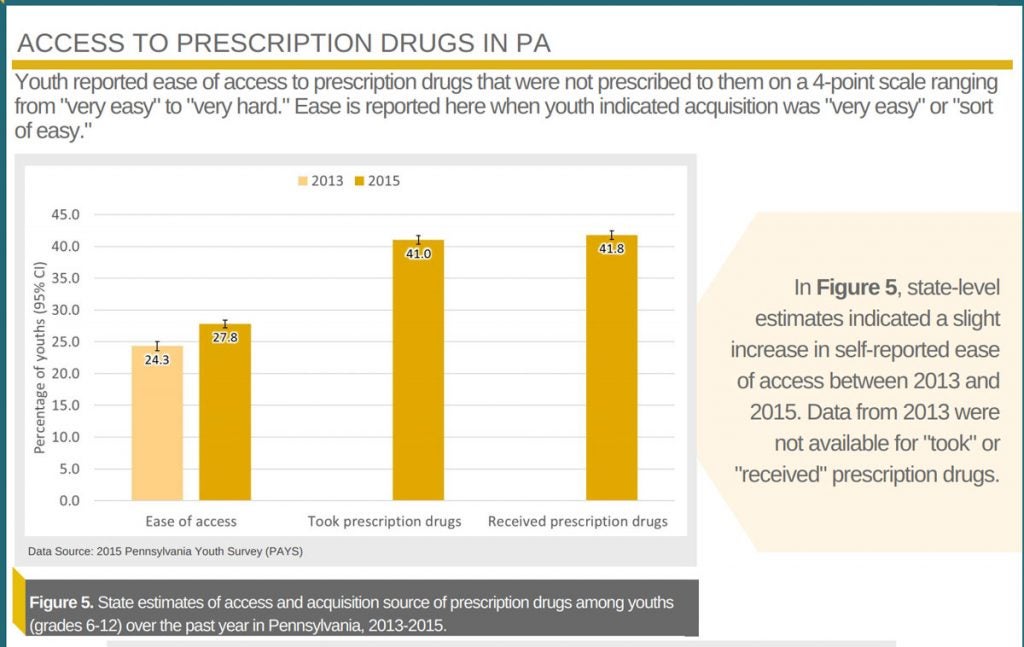

Assessing ease of access

In Pennsylvania, a team out of Drexel University issued a report that aggregated data from several U.S. and statewide youth surveys. Between 2013 and 2015, the overall perceived risk of opioids from those 12-17 went down from 86 to 82 percent. And during the same time period, more young people — up from 24 to 27 percent — reported easy access to prescription drugs.

Philip Massey, who worked on the report, and said a “one-size fits all” approach to the problem won’t work. He advocates drug take-back programs for adults to dispose of excess prescription pills, and he recommends educational programs geared to parents and kids.

“Having data to help drive some of the prevention strategies is going to be really important to respond to an important and nuanced epidemic,” he said.

“Cause when they get to the ERs yes, we’re doing a great job of saving their lives, but how do we go a little more upstream?”

Kane agreed that messaging to parents and prescription drug users is key.

“People get a prescription, and they stop their conversation with, ‘What does this mean to me?’ Perhaps with this class of drugs, the conversation needs to go one step further about the risks to all the members of the household,” he said.

The data in the the University of Chicago report comes from 31 children’s hospitals around the country, drawn from a broader database called the Pediatric Health Information System to which Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia feeds data.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.