Pennsylvanians’ growing sentiment to make elections fair

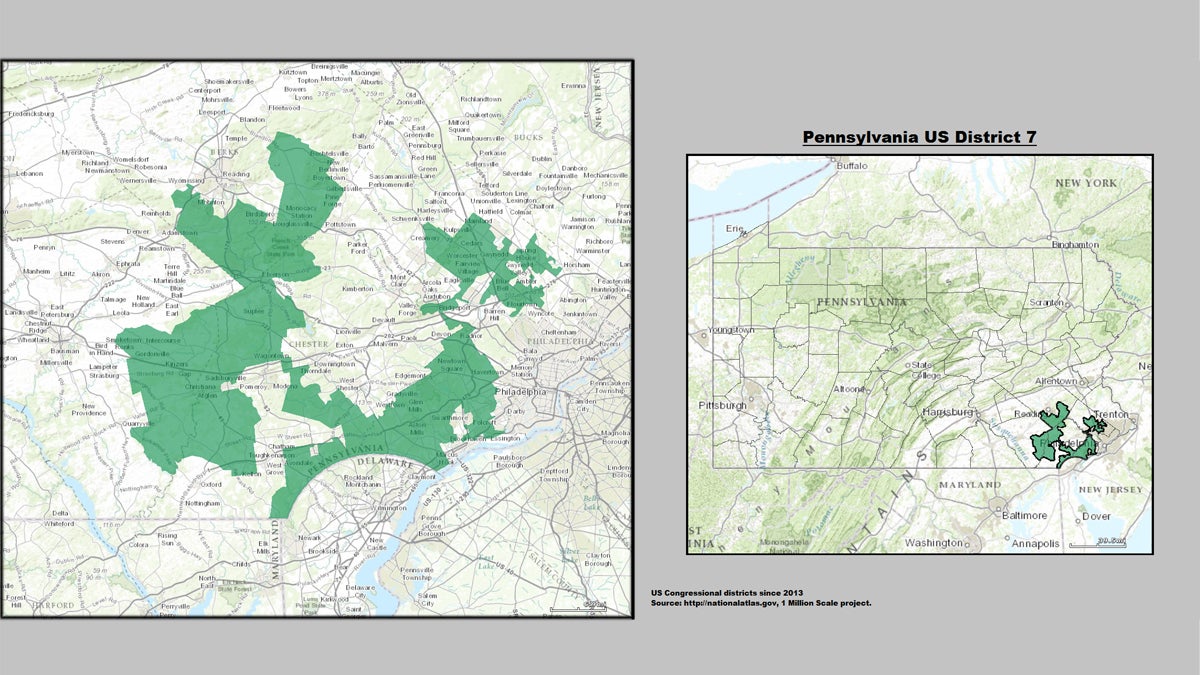

Pennsylvania's infamous 7th U.S. Congressional District is said to look like “Goofy kicking Donald Duck.” (United States Department of the Interior)

There were no pitchforks or torches when I attended a public forum earlier this month at Chestnut Hill United Church about how Pennsylvanians could — just maybe — restore some fairness to the political process

Currently, lines are drawn by a politically embedded committee of five, including the majority and minority leaders of the Pennsylvania House and Senate. Boundaries change roughly every decade, on the heels of the national census. Ideally, districts are to contain about the same population and be geographically “compact and contiguous.”

Not surprisingly, career politicians have engineered the process to work to their own benefit through a process known as gerrymandering. It consists of dividing geographic areas into representative districts that advantage one party or group over another. The term originated in 1812. A journalist with The Boston Gazette noted that a Massachusetts electoral district had taken on the shape of a salamander to benefit Gov. Elbridge Gerry. Soon, gerrymander was in common use.

Areas with 50-50 registrations most vulnerable

Keith Forsyth, Philadelphia coordinator of Fair Districts PA, a nonpartisan grassroots volunteer movement to change how political boundaries are set, clicked through a short presentation. He ran down the varieties of gerrymandering. Sweetheart gerrymandering tailors districts to protect incumbents of either party. Packing concentrates voters of the out-of-power party in as few districts as possible to reduce their influence, while cracking does the opposite, splitting a voting community across districts to dilute influence.

Areas in which voters are fairly evenly divided between parties, as Pennsylvania is*, are most ripe for gerrymandering, precisely because elections can turn on a few districts shifting. In other words, votes in balanced areas really matter, and the majority of incumbents prefer not to leave their reelection in that much doubt. They prefer a system that reliably returns them to office, term after term after term. Hence, gerrymandering.

* As of March 6, 2017, Pennsylvania had about 4.1 million registered Democrats, 3.2 million registered Republicans, and 1.2 million voters in other parties or without political affiliation.

Representatives in areas designed to support re-election can afford to be more extreme in their views, playing to the base that will protect their seats rather than moderating positions to appeal to the broadest number of voters. The problems flowing from such an arrangement are all too apparent. Elected officials who have no incentive to cooperate retreat into polarized camps, and nothing gets done.

Independent voters marginalized, disenfranchised

More than that, moderate voters, who are in the majority, are marginalized and frustrated to the point that they withdraw from the whole process, not bothering to cast votes or express their views to representatives. Which makes change even less likely. In a very real sense, gerrymandering blocks majority rule.

In a gerrymandered system, frustrated voters may choose to register as independents. In Pennsylvania, independents can’t vote in primaries, which because of gerrymandering, may be the only meaningful elections.

Independent ranks are growing with the dysfunction of the major parties, and government in general. According to the group Independent Pennsylvanians, more than a million voters in the state were registered independents in 2009, which represented an increase of 257 percent since 1994. National estimates indicates that 40 percent of all voters identify as independent, regardless of party registration — which makes independently minded voters more numerous than those identifying strongly with either the Democratic or Republican agenda.

A bipartisan scheme

Gerrymandering is practiced by both parties. The development of mapping software has created devastating efficienct in curating voting districts to preserve incumbents’ seats. It has made the difference in elections.

Fair Districts PA provides the following national example from the 2012 Congressional elections: “Democratic candidates for the US House of Representatives outpolled Republican candidates nationwide by roughly 1.4 million votes. But Republicans emerged with a 33-seat majority in the House, capitalizing on the crafty GOP gerrymandering devised by [Republican strategist Karl] Rove and others.”

Only chickens should guard the henhouse

Instead of allowing politicians to control redistricting, Fair Districts PA supports a commission comprising independent individuals. To institute that change is a lengthy process. The Pennsylvania legislature must approve a bill in two consecutive sessions, which puts it on the ballot as a referendum. Time is short for all of that to be accomplished before the next round of redistricting after the 2020 census. Nevertheless, Forsyth noted that public meetings across the state have been drawing crowds. And make no mistake: If 150 people show up on a beautiful Sunday in Chestnut Hill to hear about redistricting, something is going on.

At present, bills are being introduced in both chambers of Pennsylvania’s legislature to change the way boundaries are drawn for what are currently 18 congressional, 50 state senatorial, and 203 state house districts.

Senate Bill 22 was introduced in the Pennsylvania Senate by Sen. Lisa Boscola, a Democrat representing Northampton and Lehigh counties, and Sen. Mario Scavello, a Republican representing Northampton county, to create a redistricting commission of 11 nonpartisan citizen volunteers who meet criteria developed by the Pennsylvania Secretary of State. The commission would be prohibited from setting boundaries that unfairly favor or disadvantage one party.

In the Pennsylvania General Assembly, bills have been or will be introduced by Tina M. Davis, D-Bucks; Ed Neilson, D-Philadelphia; and Brian Sims, D-Philadelphia.

Getting the word out

Public input is critical and time is short to get redistricting reform on the ballot. In March alone, Fair District volunteers made more than 30 presentations across the Commonwealth, speaking to groups from Lancaster to Lockhaven, Philadelphia to Pittsburgh, Wyomissing to Montrose, and Harrisburg to Stroudsburg.

And while marching is viscerally satisfying, building a voting system that compels representatives to consider the entirety of constituent views, rather than just the extreme fringes, will produce the change we all want to see.

—

On Thursday, March 30, at 7 p.m., Bryn Mawr College will host “Redistricting & Representation: How to Solve Pennsylvania’s Gerrymandering Problem” an educational public forum led by Carol Kuniholm, co-chair of Fair Districts PA and election reform specialist for the League of Women Voters of Pennsylvania. The event will be held at Bryn Mawr’s McPherson Auditorium, 150 N. Merion Ave, Bryn Mawr, Pa.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.