Part Two: Ontario celebrates diversity, but still works to close achievement gaps

Part two of our Ontario series

Eight year-old Sirvat Labiba emigrated with her family from Bangladesh to Ontario, Canada when she was three. She lives in the Crescent Town neighborhood of Toronto with her mother, father and little sister in a high-rise apartment tower.

“Most of them are pretty dirty,” she said. “They built it a really long time ago. So it’s, like, really old.”

Even if the housing isn’t ideal, Labiba is thrilled to live in Ontario.

“It’s a better community, because in Bangladesh, when people get sick it’s really hard for them to get better. And so this is, like, a better community for children to learn,” she said.

Educators in the United States tend to take international comparisons of public school systems with a big grain of salt.

Many of the other countries that rank highly on international tests serve such homogeneous populations that it can be challenging to make fair and useful comparisons. Think: Finland, Singapore, and South Korea.

But the academic success of students like Labiba is one of the things that makes Ontario stand out internationally. The system has been heralded worldwide while serving a large minority population and embracing multiculturalism.

Overall, Ontario and Pennsylvania are comparable in the proportion of minority students they serve. In Pa., minorities make up about 32 percent of the public school population. In Ontario, it’s 20 percent.

In Toronto, though, diversity levels are off the charts. A whopping two-thirds of students in the Toronto District School Board are from immigrant families where both parents were born outside Canada.

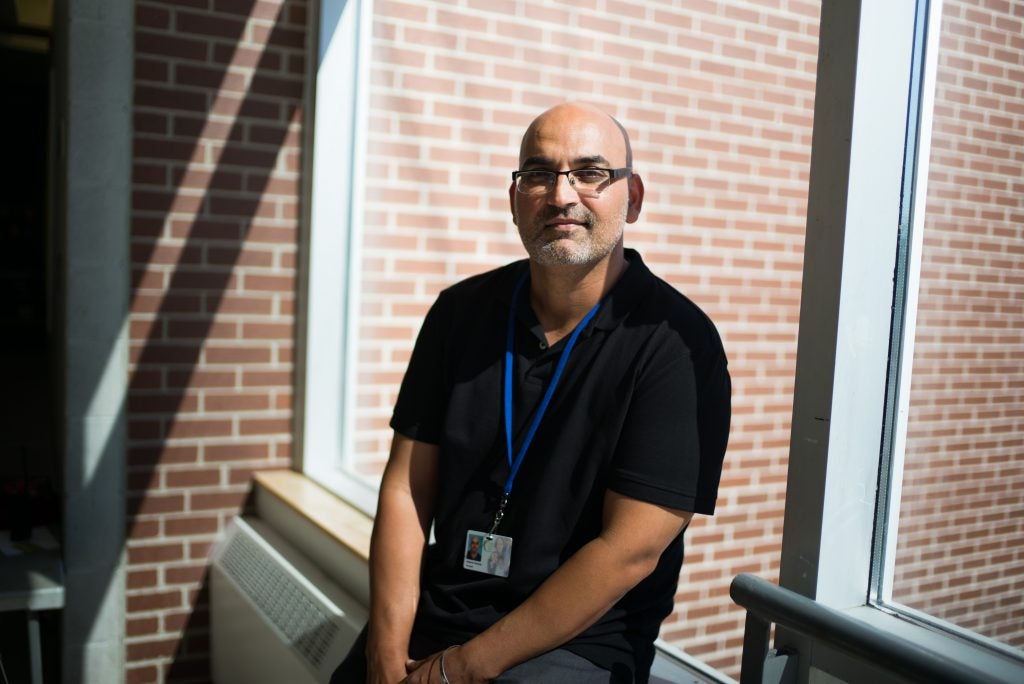

“Being Canadian, you know, a big part of that, is, well, ‘You’re Canadian, but where did you come from?’” said Harpreet Ghuman, with a laugh. “And I love that about our system and our city and our country.”

Ghuman is Labiba’s principal at Crescent Town Elementary, where most families live in the surrounding high-rises and earn under $30,000 per year.

Cultural capital

Ghuman also emigrated from South Asia when he was a child. He grew up in one of Toronto’s most disadvantaged communities, and the experience has helped him become a leader in championing the diversity of students.

“It is very personal, because I’ve lived it. I see the inequities,” he said. “But I also see what’s possible when those playing fields are leveled, when the barriers are removed.”

Like Labiba, many of the students in Crescent Town are Bengali, but there’s representation from nearly every corner of the globe. Ninety-two percent of kids learned English as a second language.

“These families, let me be clear, come to Toronto and Canada with a lot of social capital, a lot of cultural capital that is of a benefit,” said Ghuman. “It’s not sort of, ‘Oh, you know, poor kid coming into my class, what can I do for you?’ That’s not at all who we want to be as a system.”

For Labiba’s fourth-grade teacher, Tarin Kandaker, a big part of acknowledging that capital means crafting lesson plans centered on her students’ experiences.

“When you’re writing questions, and these questions are related to what they know, they’re able to relate to it better. They’re able to understand it and process it,” she said.

Parent outreach has also been key to success in Ontario. Many of the parents in Crescent Town are well-educated and were professionals in their home countries, and the school regularly invites parents in to speak to students about their experiences.

By recognizing parents as assets, the school has made itself the cornerstone of the community.

And this, in turn, has made the job of educators more manageable.

“I actually call this place Disney World when I come to work because, truly, it’s a dream to have such a community where they’re so dedicated to education, and appreciate and work with the teachers as much as they do,” said teacher Laura Lloyd.

Yasmeen Hassan was once one of those parents. She moved to the neighborhood from Bangladesh with her children 20 years ago and started volunteering at the school. She worked her way up the ranks, earned a teacher certification, and now runs the English language learner program.

“The parents have gone through a lot, so I have empathy for them, because I’ve gone through the same route. That’s something I really value, and I also believe that, as teachers, those children are not empty vessels. We’re learning from each other,” she said.

Differing views on immigration

This inclusive mindset is promoted up and down the ladder in Ontario public schools, and it exposes a cultural difference between mainstream thought in Ontario compared to the U.S. on immigration.

Where many in the U.S. view immigrants as a threat to the job market, Ontario actively pursues them to replace its aging workforce and build its economy.

A 2010 report on Ontario by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) highlighted this distinction.

“It is an attractive destination for immigrants, and immigrants are welcomed as part of both a cultural commitment and as an economic necessity,” it says in the report. “The majority of immigrants who come to the country are selected to fill economic needs. This means that they are not seen as a threat or as competing for jobs and increases the political support for their continued arrival.”

At Crescent Town, and many other diverse schools in Toronto, all of this concentrated support and inclusivity has added up to very impressive results on province-wide tests.

And by some measures, Canada’s tack has proven extremely effective overall. OECD, which administers the international PISA test taken by 15 year-olds, finds that within three years of arrival in Canada, immigrants score “remarkably strong” by international standards.

It’s harder, though, to ferret out how different subgroups perform on Ontario’s province-wide standardized tests because the education ministry does not divide results by ethnicity or race.

Some individual school boards, though, have opted to disaggregate results. Toronto does, and the outcomes have been mixed: some ethnicities have done very well; others haven’t.

Grappling with achievement gaps

The biggest question in Pennsylvania along these lines has been about how to close achievement gaps between black and Latino students and their white peers.

The most recent federal report on Pennsylvania shows significant gaps between these subgroups in graduation rates and proficiency on state tests.

Pa. also continues to post substantial achievement gaps on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), known as “the nation’s report card.”

Despite two decades of reform attempts in Pennsylvania, the 2015 NAEP found that these gaps were “not significantly different” than those in 2002.

Students who are poor, learning English, or have special education-disabilities also continue to lag behind their peers. The state tracks these students under a “historically underperforming” label.

A Keystone Crossroads analysis of Pennsylvania’s 2016 standardized test results finds that fewer than 10 percent of elementary and middle schools statewide have at least half of their “historically underperforming” students performing on grade level in English, math and science.

Of those, just 11 schools across the entire state enroll more than 200 of those students.

No magic bullet

On this measure, Ontario can’t offer a magic bullet.

Despite its own series of fiscal reforms and its commitment to equity, significant achievement gaps persist there as well.

A 2014 Toronto District School Board report on the subject shows black, Latino and Middle Eastern students performing well below white and Asian peers on provincial tests. In some instances, the achievement gap across ethno-racial groups was as much as 50 percent. In 6th grade math for instance, 88 percent of East Asian students scored proficient compared to 35 percent of black students.

The same report found that although overall suspension rates have gone down in recent years, black students were still suspended at much higher rates than other subgroups.

Karen Faulkner, an executive superintendent in TDSB, credits the city system for acknowledging these gaps and actively working to close them. She says the province at large can do a better job of following suit.

“I think we’re all too fond of talking about where we do a good job,” said, “but we never actually talk about the specific groups who aren’t achieving well in our schools.”

There were also some encouraging trends in Toronto’s data.

Over a four year period, students in every racial subgroup increased proficiency rates in most grades and tested subjects. And achievement gaps significantly narrowed between Latino and white students in grade three.

But the gaps that persist are clearly troubling. And they raise questions about the ability of even the most equitable of education systems to deliver on the promise of giving all students the education they need to thrive.

Faulkner believes Ontario, though, is poised to make a breakthrough, with Toronto at the forefront.

“We know what our mission is, and we have phenomenal leadership,” she said. “It’s very exciting times ahead, but it better translate into good results for kids, or we will have blown it.”

In the next segments in this series, we’ll dive into some of the key ways Ontario leaders think they can spur this change.

And the plans don’t include the most common answers in Pennsylvania.

Keystone Crossroads explores the urgent challenges pressing upon Pennsylvania’s cities. Four public media newsrooms are collaborating to report in depth on the root causes of our state’s urban crisis – and on possible solutions.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.