Once upon a time, the world was sweet on Philly’s sugar industry

To pedestrians and motorists crossing the Ben Franklin Bridge, the sign is unmistakable: “WILBUR’S” painted in ghostly letters on a huge brick wall on the north side of the bridge—just a fading whisper of its former tenant.

Wilbur’s was a chocolate manufacturer in the 19th century, one of the major businesses in Philadelphia at the time. Now loft apartments called The Chocolate Works, the building is one of the last remaining artifacts of Philadelphia’s 19th century sugar rush.

In addition to ships, trains and textiles, candy was a major element of the “Workshop of the World.” Sugar refineries dotted the Delaware River hungry for cane molasses shipped up from the cane fields of the Caribbean.

“Some of the biggest sugar refineries in the world were located in Philadelphia in the late 19th and early 20th century,” said Ryan Berley, who co-founded candy store Shane’s Confectionery with his brother Eric. The brothers also are co-curating “Oh, Sugar” at the Independence Seaport Museum.

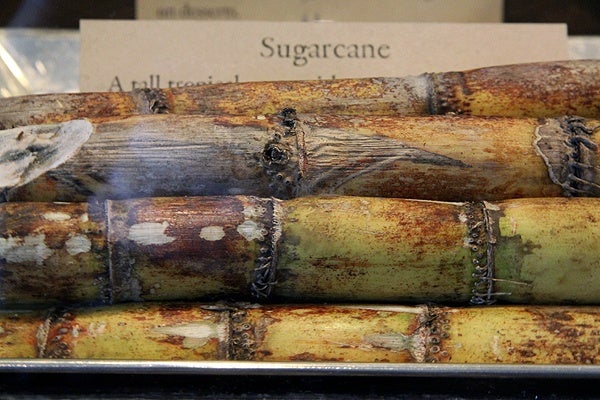

The exhibition of objects related to the sugar trade, process and candy-making comprises objects primarily culled from the Berley collection. Items include everything from machetes used to cut sugar cane, to 19th-century hand-cranked machines used to cut sheets of sugar into hard candies.

By the year 1900, there were 117 manufacturers of chocolates and candies in Philadelphia, supplying more than 1,000 candy shops in the city. At one time, the Franklin Sugar Refinery was one of the largest in the world, controlling 90 percent of America’s sugar.

Bitter realities of sugar trade

The business of sugar was not always sweet. Ships built in Philadelphia would sail to Africa for the slave trade, then to the Caribbean to drop off slaves and pick up barrels of molasses, then back to Philadelphia to sell that molasses on the docks.

During the Colonial period, refined sugar was a luxury item, used only in posh parlors during tea. Along with tea, sugar was one of the commodities on which the British levied a tariff, leading to the War of Independence.

At the time, simple candies for children were made mostly from molasses, the black slurry that sugar cane was boiled into before it could be further refined into white crystals—an expensive process. As the Industrial Revolution streamlined that process, cheap white sugar could be used to make brightly colored candies of any stripe, replacing those old molasses chews.

Berley and his brother have meticulously restored Shane’s Confectionery on Market Street to its original condition as a 1910 candy store, with brass scales and glass jars filled with candies made by hand upstairs. The Berleys’ near-obsessive affinity for 19th century Americana is the last reminder of Philadelphia’s once-great sugar industry.

“The last sugar refinery was torn down in 1983—the Jack Frost refinery on the location of SugarHouse” casino, Berley said. “You won’t see a lot of vestiges of refineries today. The lithographs in the exhibition show these tremendously large complexes of brick buildings on the river. Those just aren’t existing any longer.

“You can go to Sugar Mom’s on Church Street and have a drink in the oldest refinery left in America—1792. That’s been turned into a loft building,” he said. “That’s pretty cool.”

“Oh, Sugar!: The Magical Transformation From Cane To Candy” continues through Feb. 17 at the Independence Seaport Museum on Penns’s Landing.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.