On D-Day a dentist helps a wounded engineer

The fake eye an Army dentist constructed for Capt. Arthur F. Hoffmann became one of the few positive things Hoffman shared with his family about D-Day.

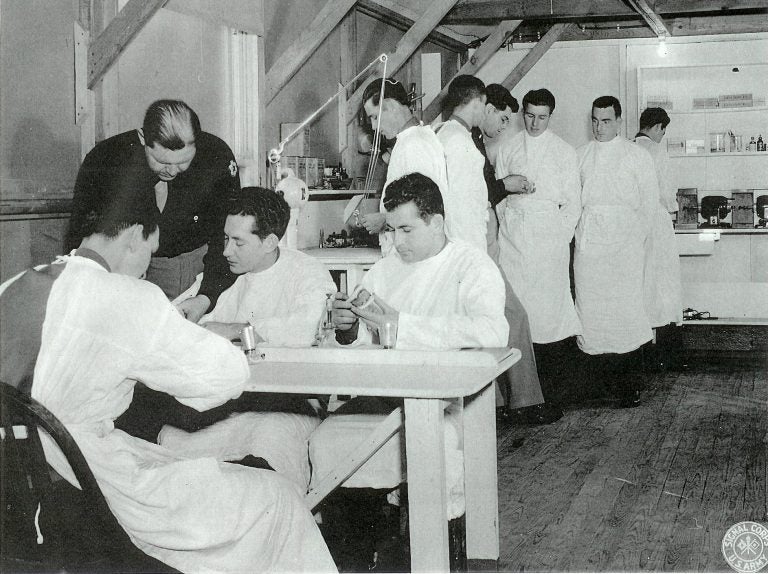

Capt. Charles W. Felt (in black tunic in background) training members of the U.S. Army Dental Corps at the 186th General Hospital, Fairford, UK. (Courtesy U.S. Army, National Archives, Washington, DC.)

U.S. Army Capt. Arthur F. Hoffmann was anxious — his landing craft was hitting the swells hard in the half-light of dawn off the Normandy coast, seventy-five years ago today.

As a supply officer in the 1st Engineer Combat Battalion, Hoffmann was to clear obstacles set by the Germans to make way for the thousands of Allied forces soon landing at Omaha Beach. On the boat, he began thinking of his wife and two-year-old daughter Emmy back in New England.

Then it struck — a shell from a German 88 anti-aircraft gun — high up on the boat, spraying shrapnel that hit Hoffmann in the eyes.

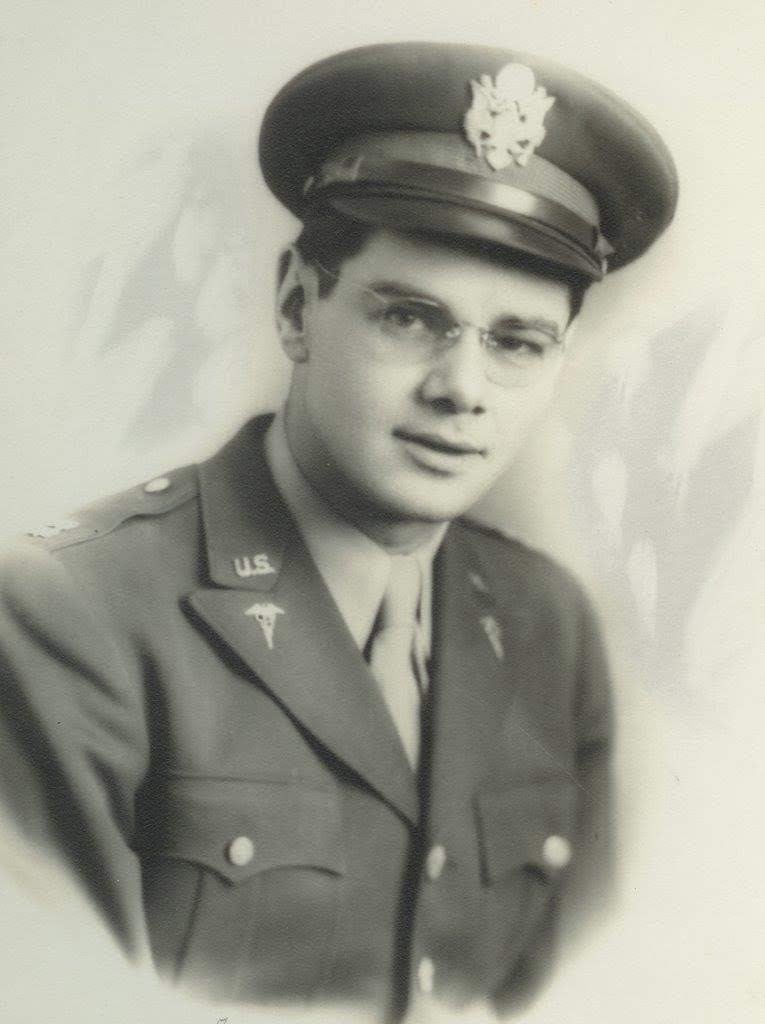

At the same time, in a hospital across the English Channel, my maternal grandfather Capt. Charles W. Felt, a dentist from small midwestern town, readied for the wounded men who would require state-of-the-art facilities and the steady hands of doctors far from the battlefield. According to medical histories of the war, specialists were often in short supply so dentists would be called upon to treat head wounds.

Last week, one of Hoffman’s daughters, Sydney Hoffmann, contacted me. She was conducting online research for a trip to Normandy and had come upon a 2014 article about my grandfather’s service in the war. She knew that a dentist undertook an unusual and cutting-edge procedure upon her father in June 1944 at a hospital in central England.

Was my grandfather the dentist who saved her father?

Not long after Capt. Hoffmann’s landing craft was hit, another boat pulled alongside. On board was then-correspondent Ernest Hemingway.

“I saw a ragged shell hole through the steel plates forward of her pilothouse where an 88-mm. German shell had punched through,” Hemingway wrote in the Collier’s magazine article. “Blood was dripping from the shiny edges of the hole into the sea with each roll of the [landing craft].”

On the rescue boat, Hemingway gave Hoffmann a pair of sunglasses to protect his eyes until he could get to the hospital, Hoffmann’s daughter Sydney said.

The day so far had been chaotic for the engineer battalion. The sea was rough, there was rain, a landing craft for tanks broke down early, and others were swamped in the swells. After Hoffman’s boat was hit, the rest of the battalion landed, but nowhere “near where we were supposed to,” said Lt. Col. William Gara, the battalion commander, in the book, Omaha Beach, by Joseph Balkoski.“And as a result, there was mass confusion.” Nonetheless, the battalion opened a road for tanks, field pieces and wheeled vehicles. It received its third Presidential Unit Citation and the French Croix de Guerre with Palm that day, but lost as many of 41% of its original strength.

One loss was Hoffmann.

At the 186th General Hospital in Fairford, England, where my grandfather was stationed, staff worked on more than 5,200 soldiers during the six months that followed — an average of one patient every half hour, according to a report I found in the National Archives. They wired 17 jaws, sutured 34 mouth wounds, splinted eight limbs, filled 1,345 cavities, pulled 973 teeth and constructed 80 eyes.

Yes, eyes.

Prosthetic eyes had been made from glass supplied by German companies, but the Allies needed an alternative. Dentists discovered that the acrylic resin used for dentures made an excellent replacement material for the glass that was in short supply because of the war. Army Capt. Stanley F. Erpf, a dentist, produced the first acrylic eye and implemented a training program, according to the book, U.S. Army Dental Service During World War II, by George Jeffcott. About 10,000 eyes were made in the first eighteen months of the program. Hence, the modern practice of ocularistry was born. Making a good false eye requires both skill and craft, requiring an artisanship like shoemaking or blacksmithing, resisting industrialization even today.

Sydney and her sisters made the connection.

“Our dad mostly talked about the dentist who surgically repaired the muscles and tendons of his face and fashioned an eye out of materials used for making false teeth,” Sydney said. Another clue was that the hospital in which Hoffmann was treated was in central England and built upon a former deer park — land bounded by earthworks to keep the prey for hunting by nobility.

“Honestly that dentist saved my father’s soul in some way,” Sydney said. “That’s what my father talked about.”

Before the war, Arthur Hoffmann was thirty-one years old, started a business and attended the School of Design at Harvard University, Sydney said. He lived in West Hartford, Conn., with his wife. His first-born was hardly a month old when he enlisted. He joined the 1st Infantry Division, known later as the famous “Big Red One” for the large numeral on their shoulder patches. The Division participated in North Africa and Sicily before moving to England.

“My father was super appreciative of your grandfather,” said another of Hoffmann’s daughters, Jennifer Hoffmann Beard. “Dad thought it was very unique that a dentist did it and used dental materials to do it. He copied the color on the eye, so that it was not just a placeholder. It looked like an eye. It was very artful.”

Trauma and Caregiving

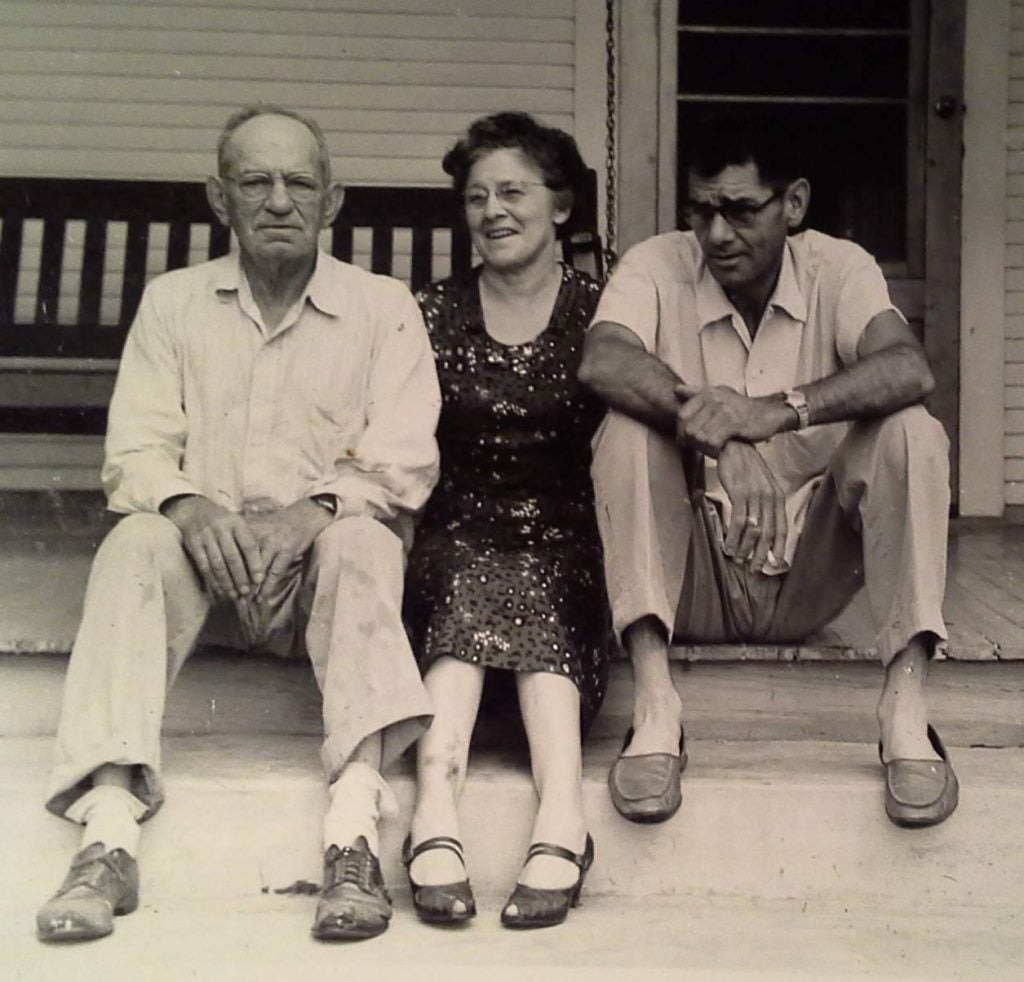

Shortly after D-Day, my grandfather transferred to hospitals in England, France and Belgium. He remained after the war took care of German prisoners and homeless civilians. He wrote to my grandmother Trudy about his unhappiness that he couldn’t leave. He arrived finally in April 1946 with a puppy, “Midge,” smuggled in his fatigue jacket. His daughter — my mother Connie Jean — was 6. He was never the same again, my grandmother told me.

He was slowly going blind, suffering with a sudden onset of neuritis in his left eye. While his dental practice was successful — he built a new house and purchased cars and boats — he was restless in the day and sleepless at night. He drove his cars fast and had nightmares. In July 1957, he died in a single-car accident 11 years after his return — just one day after the anniversary of his induction into the Army.

My grandfather was an easy-going man, known affectionately as “Blacky” for his five-o’clock shadow. I wondered whether he suffered from what today is called caregiver trauma. Jonathan Shay, a psychiatrist at the Department of Veteran Affairs, has written several books on trauma and veterans. “A trauma dentist — in a sense what your grandfather was forced to do likely without a shred of training — has a constant diet of facial disfigurements,” Dr. Shay said. “Whole jaws shot away, sides of faces blown off, people with their eyes destroyed. It is horrific to think of what he likely had a steady diet of and could not get away from.”

I couldn’t help but feel my grandfather’s experience seemed insignificant when placed against the experiences of the thousands of men, like Hoffmann, who were actually wounded at Normandy.

I asked my great aunt Irene Felt about him. She said that he spoke to her about “triage” at the war hospitals under which he served — the decision not to treat mortally wounded patients. “He told me that he had to make decisions in several cases, decisions that would end someone’s life. It really bothered him more than I had seen him bothered. Though he spoke about it as if it’s just what you had to do.”

Returning Home

Back in the States, Hoffmann was treated at Halloran General, the military hospital on Staten Island. He was promoted to Major and received the Purple Heart. He started a landscape architecture practice and fathered four more children. He joined the local VFW and rose in its ranks.

At home, Hoffmann was a loving father, Sydney said. “He could identify every plant, tree, animal, bird, even by their Latin names. He could draw anything; he played piano, guitar, and accordion; he read to my siblings and I every night. Uncle Wiggily and Thornton W. Burgess books. He taught us how to fish, and wax the runners on our flexible flier sleds in the winter. But the war wrecked him,” Sydney said. “Dad had a drafting table in his office making drawing of buildings and then all sudden he had no depth perception. He used to go behind house and set up lines of targets to get his good eye to focus, but it was never the same.”

He hated loud noises and wanted to be by himself. “The number of my classmates’ fathers who were alcoholic or committed suicide or became total failures by community standards, they were all the veterans of World War II,” Sydney said. “It was catastrophic. We all talked about as kids but didn’t have resources to process.”

On numerous occasions over the years, shrapnel surfaced on Hoffmann’s skin. “I remember him coming down the stairs with a piece of gray metal in his hand,” Sydney said. “It had popped through his skin.” Shrapnel threatened his good eye, partially detaching the retina, but vision remained. Later in life, he withdrew from civic life, even from the VFW. He suffered from Parkinson’s disease, which family members attributed to his head wound. Hoffmann died at age 85 in 1996.

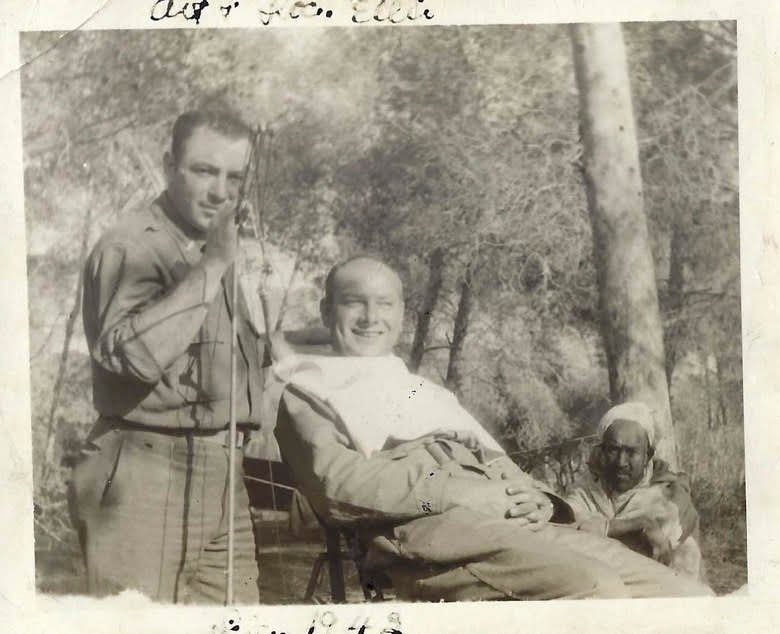

Capt T.H. Crowly, 1st Lt. K. Reinhart, (Courtesy family of Arthur Hoffmann)

“He didn’t talk about war much, but he did talk about the dentist who made his prosthetic eye,” Sydney said. “All five of my siblings took it to show and tell in grammar school. It was the only really very positive story he told. He had this thing. What happened to him was very bad, but here was this story that captured our imaginations.”

—

Michael Carolan is a Professor of Practice in the Department of English at Clark University in Worcester, Mass. His paternal father, grandfather and great grandfather were born in Philadelphia. He has been a generous member of WHYY since 2013.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.