Not easy to catch dog star exhibit in Philadelphia

At first glance, the new exhibition at the Print Center, in Philadelphia’s Rittenhouse Square, seems to be actively evading its audience.

The sign that normally hangs above the door of the Print Center has been removed, replaced by an illuminated circular disk containing a close-up image of swirling dog fur. A nearby speaker pipes out a recorded loop of an original piece of music composed by the artist, Demetrius Oliver, but he performed it on a dog whistle, making it inaudible to humans.

The exhibition is only open for one hour in the evening – from 7 p.m. to 8 p.m., Tuesdays through Saturdays. The artist has refused to grant TV, radio, and podcast interviews.

It is a shadowy approach to a show about the brightest star in the night sky.

“Canicular” is a meditation on Sirius, the dog star. Oliver took over both floors of the Print Center for this immersive installation that playfully blends the astronomical and the canine. The centerpiece is a wooden cylinder, 11 feet in diameter and 12 feet high, built into the second floor gallery. It’s a makeshift observatory with a ceiling made of a semitransparent screen. A live image of Sirius is projected onto the screen in real time, so it can’t happen in daylight hours.

The image of Sirius comes from a telescope on the roof of the Franklin Institute, across town. If the sky is cloudy, the exhibition closes.

Oliver cut a hole about 2 1/2 foot square at the bottom of the wooden cylinder. This is the door, a dog door. To enter the observatory, visitors must get on the their hands and knees and crawl.

“There’s a lot of humor in Oliver’s work,” said curator John Caperton, who has been following the artist’s career since Oliver was a grad student at the University of Pennsylvania (he is now based in New York). “It’s very metaphorical. It can be ambiguous. He gives us clues, but he does not hold your hand.”

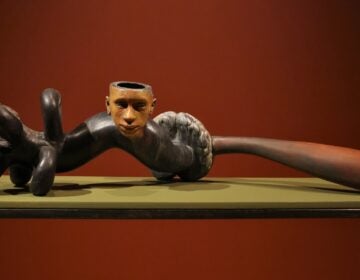

The building-wide installation manipulates the way visitors see Oliver’s work, from the green and red lights bathing the first floor (dogs are colorblind, and cannot distinguish between red and green) to forces viewers to bend, stoop, and crawl to experience the pieces.

“I saw the Print Center as material to be shaped,” said Oliver, whose installation also forced the Print Center to change the way it does business. The Center usually open to visitors during the day. Soon to celebrate its 100th anniversary, this is the first time an exhibition at the Print Center has been weather-dependent.

“He wanted to make an exhibition where somehow the role and the function of the entire organization would be shifted by the artist,” said Caperton.

Even though this show is at the Print Center, it contains only one print — a photograph of star maps. The bulk of the show is sculptural, video, and installation work. Oliver began as a photographer. Over the past few years his work has expanded into other medium, oriented around space and, in particular, Sirius. His interest is subjective, and unexplained.

Since man first looked up and wondered about the heavens, Sirius has had a leading role. As the brightest star in the sky, Sirius has been important for agriculture, navigation, and tracking the passing of seasons.

It still holds mysteries:

The star you see in the sky is actually two stars, Sirius A and Sirius B, visually they blend into each other. Thousands of years before western scientists could develop lenses and telescopes to discover Sirius was two stars, an African tribe called the Dogon knew about the second star.

“How did the Dogon know that there was a companion to Sirius, since it’s not visible to the naked eye — you need a telescope to see it,” said Derrick Pitts, chief astronomer at the Franklin Institute, who consulted on Canicular. “How did they know that the companion was there? We can’t answer that question easily.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.