North Broad a street of dreams during short-lived golden age

-

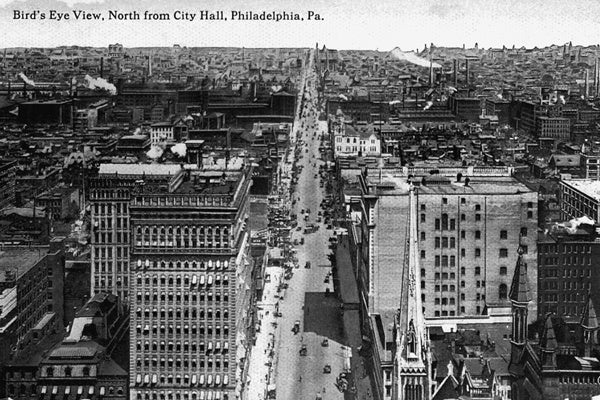

<p>A 1910 postcard shows a bird's eye view of North Broad Street taken from the Philadelphia City Hall tower. (Historical image courtesy of Arcadia Publishing.)</p>

-

<p>Across Broad from the Academy of Fine Arts in 2012 is the Philadelphia Convention Center, where the Odd Fellows Temple, Lyric Theatre and Adelphia Theater once stood. (Emma Lee/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

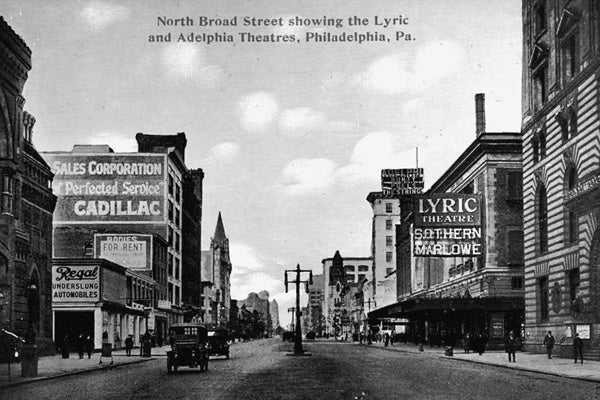

<p>The Odd Fellows Temple (foreground right), the Lyric Theatre, and the Adelphia Theater were located across the street from the Pennsylvani Academy of Fine Art (far left) in the early 20th century. (Historical image courtesy of Arcadia Publishing.)</p>

-

<p>The Masonic Temple on North Broad Street just north of Philadelphia's City Hall looks the same as it did more than 100 years ago. (Emma Lee/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

<p>The Masonic Temple was built between 1868 and 1873 at a cost of $1.6 million. (Historical image courtesy of Arcadia Publishing)</p>

-

<p>The Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts at Broad and Cherry streets looks mostly unchanged in 2012. Its surroundings, however, do not. (Emma Lee/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

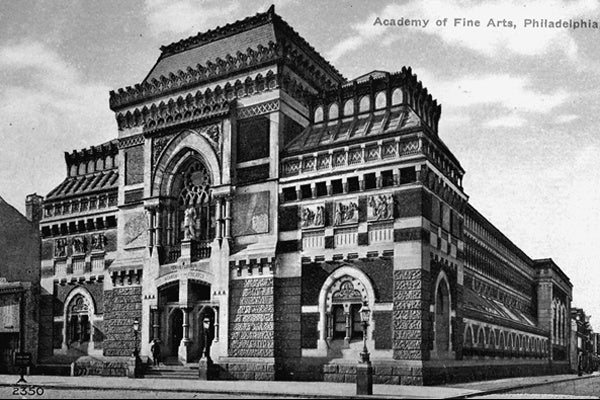

<p>The Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts by arhitect Frank Furness opened in 1876. (Historical image courtesy of Arcadia Publishing.)</p>

-

<p>The view from North Broad and Race streets today looks much different. (Emma Lee/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

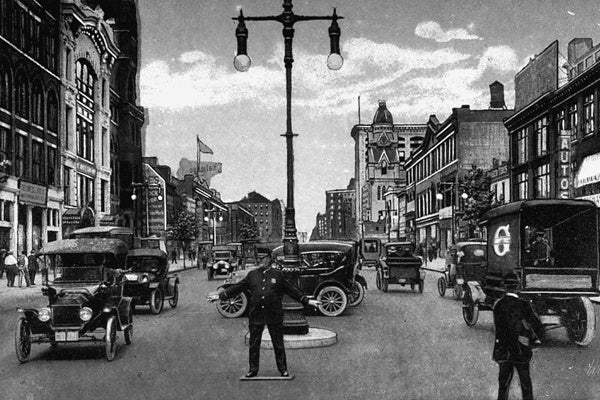

<p>A policeman is shown directing traffic on North Broad and Race streets in this 1915 postcard. (Historical image courtesy of Arcadia Publishing.)</p>

-

<p>The Park Theatre was demolished in 1968 for a new Salvation Army building at the corner of Fairmount Avenue and NOrth Broad Street. (Emma Lee/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

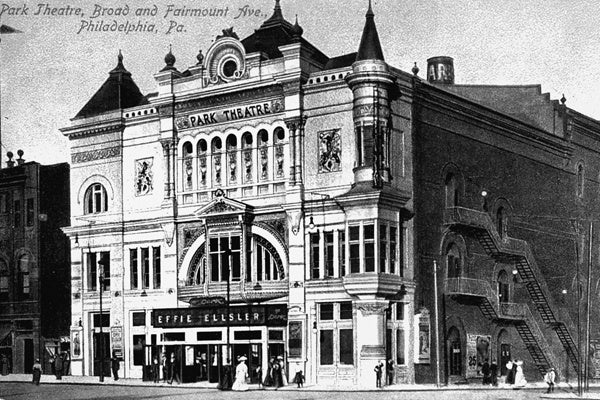

<p>A post card from 1905 shows the Park Theater at the corner of Broad Street and Fairmount Avenue. (Historical image courtesy of Arcadia Publishing.)</p>

-

<p>The site of the First New Jerusalem Society building at the corner of Broad and Spring Garden streets is now a parking lot. (Emma Lee/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

<p>Built in 1851, the First New Jerusalem Society, also known as the Spring Garden Institute, was a technical school for art and electrical apprentices. (Historical image courtesy of Arcadia Publishing.)</p>

-

<p>Today the site of the Majestic Hotel at Broad and Stiles streets is now occupied by a McDonald's and a gas station. (Emma Lee/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

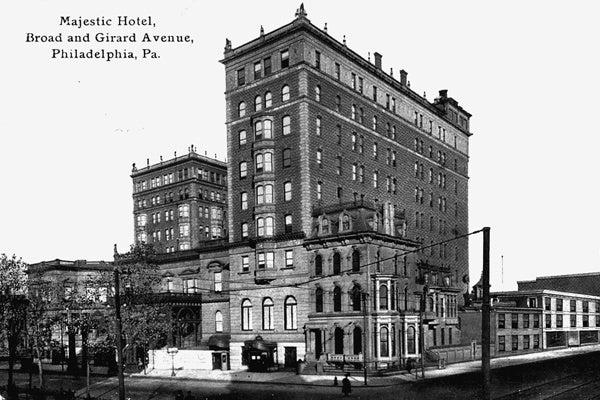

<p>The grand Majestic Hotel and apartment house was built in 1902 at Broad and Stiles streets. (Historical image courtesy of Arcadia Publishing.)</p>

-

<p>The Mercantile Club, formerly at 1422 North Broad Street, has been replaced by a YMCA. (Emma Lee/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

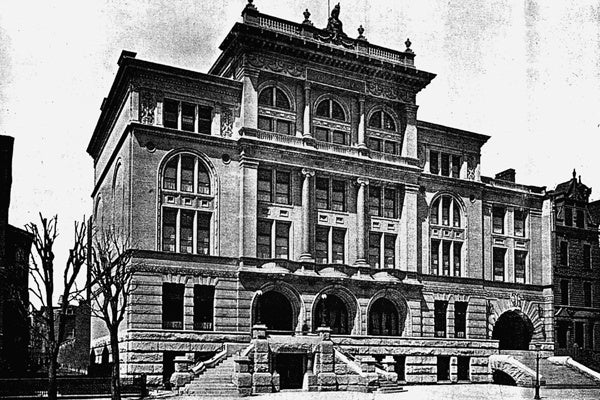

<p>The Mercantile Club was a members-only space for Philadelphia's prominent merchants and manfacturers beginning in 1894. (Historical image courtesy of Arcadia Publishing.)</p>

-

<p>The same view in 2012, facing north from City Hall, shows the statue of Civil War Gen. Fulton Reynolds and the Masonic Temple. (Emma Lee/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

<p>The image, facing north from Philadelphia's City Hall, on this 1901 post card shows the statue of Civil War Gen. Fulton Renolds to the left and the Masonic Temple on the far right. (Historical image courtesy of Arcadia Publishing)</p>

-

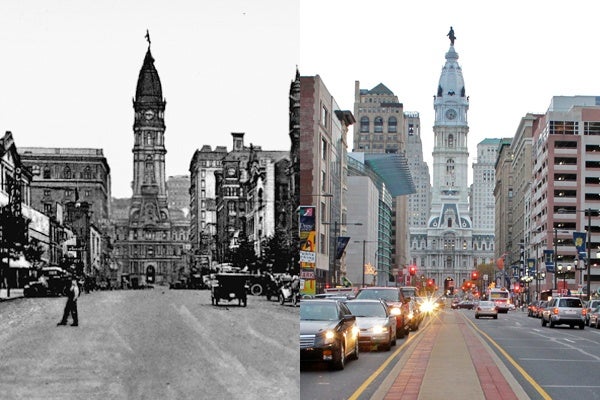

<p>A view of Philadelphia's North Broad Street looking south from Vine Street, circa 1910 (left) and 2012 (right). (Historical photo courtesy of Arcadia Publishing.)</p>

-

<p>The view today of North Broad Street from Girard Avenue looking south toward City Hall. (Emma Lee/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

Today, a tarp is placed above the church's service area to keep pieces of the ceiling from falling into the congregation. (Kimberly Paynter/for NewsWorks)

-

The Metropolitan Opera House was once home to a thriving congregation in the 50's and 60's. (Kimberly Paynter/for NewsWorks)

“I’m told this street is respectable,” says one character in Edith Wharton’s novel The Age of Innocence.

“It’s not fashionable,” comes the reply.

That’s pretty much how it was on North Broad Street in the late 19th century. The industrial revolution had begun, and Philadelphia was known as the “Workshop of the World,” making textiles, locomotives and beer.

“After the Civil War, Philadelphia was really going full blast,” said Robert Morris Skaler, forensic architect and author of Philadelphia’s Broad Street South and North. “They were making all kinds of things. North Broad Street was a great place for people to live, because it hadn’t been developed yet.”

Skaler’s book is filled with images from this golden age of North Broad, an age capped by the construction of the grand Lorraine Apartments, which are now the abandoned Divine Lorraine Hotel.

He describes what made the area so desirable.

“It was big and wide,” he said. “About six carriages could go side-by-side, so it was a great street to jump on your carriage and go all the way out, perhaps to Diamond, and then make a left and head out to the park — and also the fact that there were so many churches on the street that, on a nice Sunday afternoon, it was packed. People walking back and forth — it’s almost like a Boardwalk kind of thing going on.”

The rise of new money

So the street became populated by the so-called nouveau riche — those who made, rather than inherited their money.

Skaler says some of them included Michael Bouvier, the ancestor of Jacquelyn Bouvier Kennedy, department store owners, Alice Gimble, and industrialist Henry Disston and his son, along with P.A.B. Widener and William Elkins.

“You get these huge houses built along there,” said Skaler. “Their stables were in the back streets unlike Rittenhouse Square, where the stables and the houses were all mixed up together.”

Rittenhouse Square, of course, was where old money lived in Philadelphia.

A passage from a book called North of Broad, published by an anonymous author during the time period, is telling.

“By the way, what’s your locality? Is it north or south of Market?” he asked anxiously.

“I don’t know,” answered Helen. “It’s on Grafton Street, about a mile from Girard College.”

“Oh dear, dear,” said he, in a distressed tone. “That is all wrong. It should be two miles or two miles and a fraction at least, if my memory serves. An inch or more makes all the difference in the world your social position in Philadelphia.”

A north-south rivalry

Nowhere does this conflict play out more succinctly than in the battle for cultural superiority of the day. What South Broad Street had in the Academy of Music, North Broad emulated in the Metropolitan Opera House, built by the famous Oscar Hammerstein. In the 2000 WHYY-TV documentary A Walk Up Broad Street, architect Hy Myers said the Met represented efforts to one-up the establishment.

“The Academy of Music had 3,100 seats,” said Myers. “The Met, 4,100 — a thousand more. The proscenium of the Academy, 50 feet wide. [Hammerstein] made his a hundred feet wide. The Academy was made of brownstone on the front. He decided to make his white, marble and white brick, because he wanted his to be bigger in appearance, more glamorous in appearance.”

On the Met’s opening night, Nov. 17, 1907, the two venues had a showdown.

“Hammerstein’s Metropolitan Opera House opened with Carmen and a cast of 700,” Skaler said. “That same night, the Academy of Music opened its season with the great tenor Enrico Caruso.”

“Now Philadelphia society doesn’t know where to go,” said Myers. “‘Shall I go to the Academy? Shall I go to the Met?’ They do both!”

At intermission, the audience left the Academy, rushed to the waiting carriages and cars, and headed north on Broad Street to arrive at the Met in time to see the second half of Carmen. Hammerstein purposely delayed the opera’s intermission, thus filling all his 4,000 seats.

However, Skaler said, it was a hollow victory. Within five years, the Met went bankrupt.

Around 1920, he said, the subway was built beneath Broad Street. “And the racket and noise from them ripping up Broad Street probably got a lot of people to move. And of course the subway stops come in, and those areas become commercial, and neighborhoods change.”

A little later, industry started to sputter because of the Great Depression. Philadelphia’s Baldwin Locomotive Works shut down, laying off 17,000 people.

“We’d love to get a new industry in Philadelphia that might give us 2- or 3,000 [jobs],” said Myers. “So this was a big loss for Philadelphia, and it was the first signs that the ‘Workshop of the World’ that was Philadelphia was just beginning to fray at the edges and change.”

That change would signify the end of North Broad Street’s gilded opulence.

All historical images are from Philadelphia’s Broad Street South and North, by Robert Skaler courtesy of Arcadia Publishing.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.