Commentary: NJ students take PARCC tests and survive

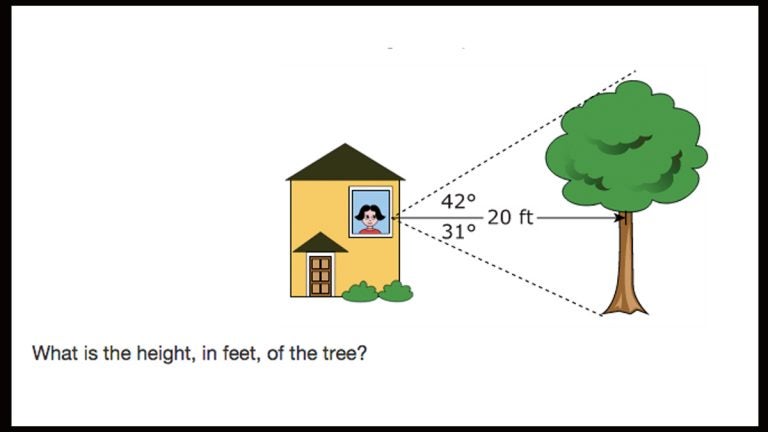

PARCC online practice geometry question

This week many of New Jersey’s students took PARCC tests, the new computer-based standardized assessments aligned with the Common Core State Standards. These tests have incited no shortage of acrimony among N.J. teacher union leaders, parents, and even some school boards, as well as predictions of mass refusals to take the PARCC.

We’re only partly into the testing period (which, dire predictions aside, seems to be going just fine) but there’s one disturbing data point that may surprise NJEA and Save Our Schools-NJ, the primary groups that lobbied against the tests: most of the opt-outers are clustered in N.J.’s wealthiest districts.

Now it’s perfectly reasonable for parents and teachers to display some degree of foreboding about PARCC tests. After all, it’s a big shift from low-bar fill-in-the-bubble tests that New Jersey students have taken for decades to new computerized tests that assess the higher-level thinking skills that inform the Common Core. Some people fear that that lower test results will ding N.J.’s reputation for fine schools, that testing pressure will eat into instructional time, and that some schools lack bandwidth capacity.

But some of that foreboding verges on fear-mongering, much of it instigated by union groups and their allies that oppose harder tests because N.J.’s 2012 tenure law links a small proportion of student outcomes to teacher evaluations.

By way of example, NJEA’s television campaign against PARCC tests features a parent of a seven-year-old (who, by the way, won’t be taking PARCC tests because kids don’t take them until third grade) crying out, “school is a fiasco” because this new tests is “sucking all the soul out of learning!”

Save Our Schools-NJ offers opt-out manuals and sponsors “anti-PARCC” events. Delran Teachers Association issues screeds that claim “the PARCC tests are not created by teachers, but corporate entities whose goal is not to improve student learning or instruction, but to promote the sale of additional ‘support material’ to cash-strapped school districts who find themselves (by design) on the failing side of arbitrary cut scores.”

Let’s all take a deep breath.

PARCC, or “Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers,” is one of two consortia formed after most states adopted the Common Core State Standards. The other one is “Smarter Balanced Testing Consortium.” Originally 26 states signed onto PARCC but, after pressure from that odd conglomeration of Tea Party Republicans and teacher union leaders, only twelve states, including the District of Columbia, remain members. Another twenty states are members of the Smarter Balanced Consortium. The rest of the states who adopted the Common Core are using their own tests.

In New Jersey, PARCC replaces the state standardized ASK tests given in third through eighth grade, as well as the much-maligned HSPA, taken in eleventh grade. All tests assess student skills in language arts and math. The cost per pupil to take the PARCC in N.J. is about the same as the cost for ASK and HSPA tests. Students will spend about 7.5 hours taking the PARCC in several chunks over the next month or so. That’s one hour longer than they spent on ASK and HSPA tests.

So after all the agitation, on Monday 96,000 students took the PARCC tests (some districts postponed testing because of icy roads) and on Tuesday 240,000 N.J. students took PARCC tests. Let’s check for casualties.

There aren’t any. Everyone was fine. The Wall St. Journal quotes an eleven-year-old in Livingston: “It didn’t seem to be as hard as we all expected,” he said. “All the teachers were stressing.” In Kenilworth, reports the Star-Ledger, Superintendent Scott Taylor, “everything ran flawlessly.” Michael Yaple of the State Department of Education told NJ Spotlight, “overall, there have been some localized issues, but when considering the sheer number taking the tests across the state, it has been generally quiet and business as usual.”

That’s a fair assessment, except in four districts that saw large numbers of students who “opted-out” of the PARCC tests. One of those districts was Delran, where high opt-out numbers can be attributed to the militancy of the local teacher union. The other three are Princeton, Ridgewood, Livingston, and that’s troubling for anyone concerned with educational equity issues.

Those three towns are wealthy and low-minority. Princeton’s median family income is $149,948 and 75% of its enrollment is white or Asian; 9 % are educationally disadvantaged. Ridgewood’s median family income is $146,977 and 90% of its enrollment is white or Asian; 6% are economically-disadvantaged. Livingston’s median family income is $133,271 and 93% of its enrollment is white or Asian; 4% are economically-disadvantaged.

So the largest cohorts of opt-out students come from wealthy and low-minority communities. Right now that’s just a data-point. One year doesn’t make a trend. But if this sort of orientation continues, then N.J. could see the beginnings of a new kind of division within the state education system: poor kids take standardized tests and rich ones don’t bother.

I’m sure this is a trend that NJEA and SOS-NJ leaders do not support. But unless they rework their lobbying strategies, they invite the perception that they do. Both groups might consider new strategies to support and improve annual standardized testing that best serves all students and teachers.

________________________________________________________

Laura Waters is vice president of the Lawrence Township School Board in Mercer County. She also writes about New Jersey’s public education on her blog NJ Left Behind. Follow her on Twitter @NJLeftbehind.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.