The bad girl wins: An original New Yorker cartoonist gets her due at the Brandywine Museum

The Brandywine Museum’s exhibition of Barbara Shermund’s cartoons aligns with the New Yorker magazine’s 100th anniversary.

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

On Friday, the New Yorker magazine turns 100 years old. One of the cartoonists that contributed to the magazine’s legendary cosmopolitan style is now on view at the Brandywine Museum in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania.

Barbara Shermund was a 26-year-old San Francisco native who’d just moved to New York City’s Manhattan neighborhood when she started drawing for the New Yorker shortly after it launched on Feb. 1, 1925. She started out doodling marginalia and went on to make nine cover illustrations and about 600 cartoons over 19 years.

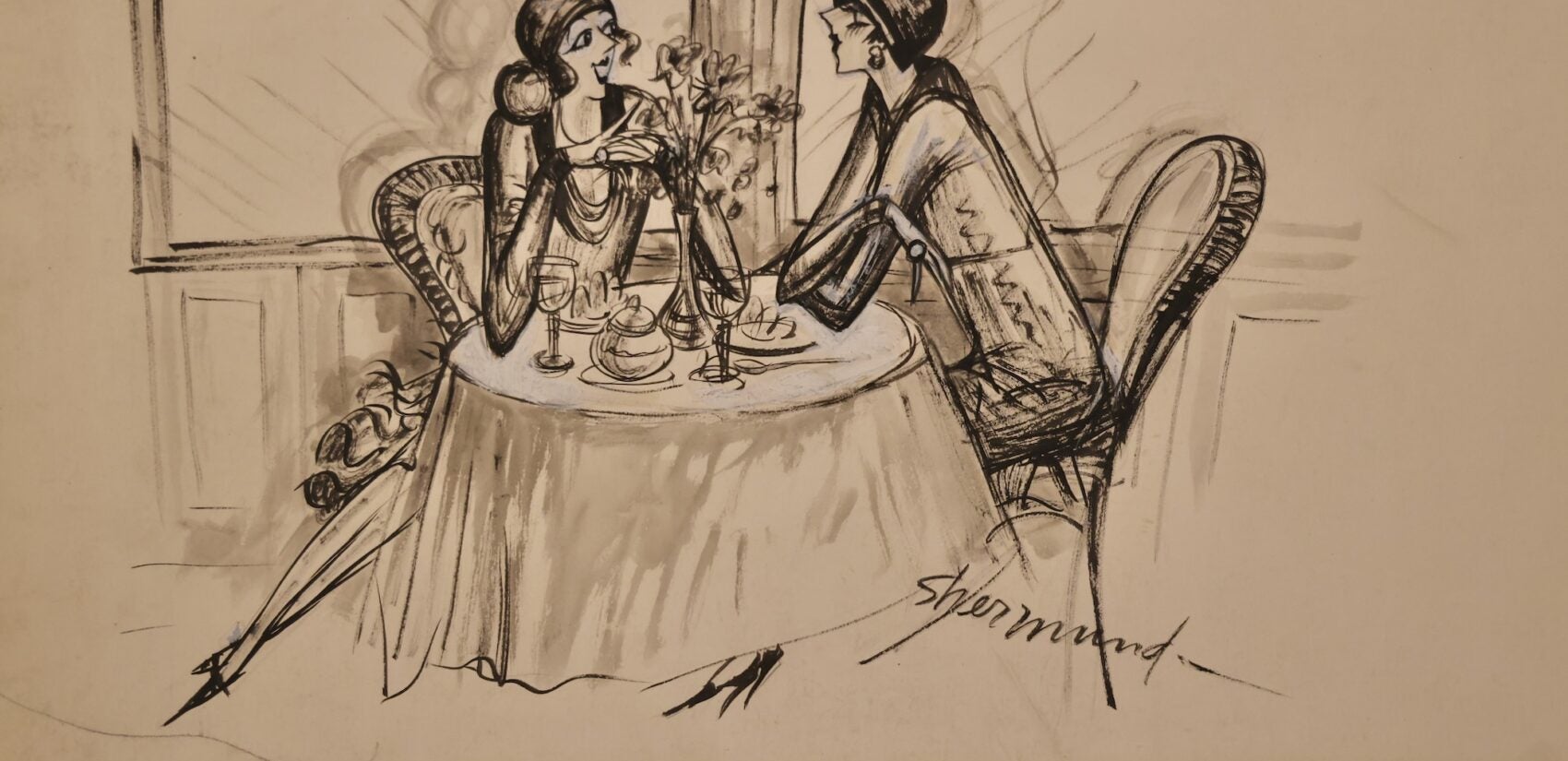

Shermund embodied the liberated flapper girl of the 1920s in both her cartoons and her life. Her work mostly features women navigating the world with sarcastic wit and chic fashion.

The languid figures in long skinny dresses with sharp heels and cloche hats are often celebrated for their bad behaviors: A woman next to a Model A asks the car salesman, “Could I get out of a jam with this?”

Two women talking over drinks at a bar: “I do say I’ll never marry—though, somehow, I’ve always wanted to be a widow.”

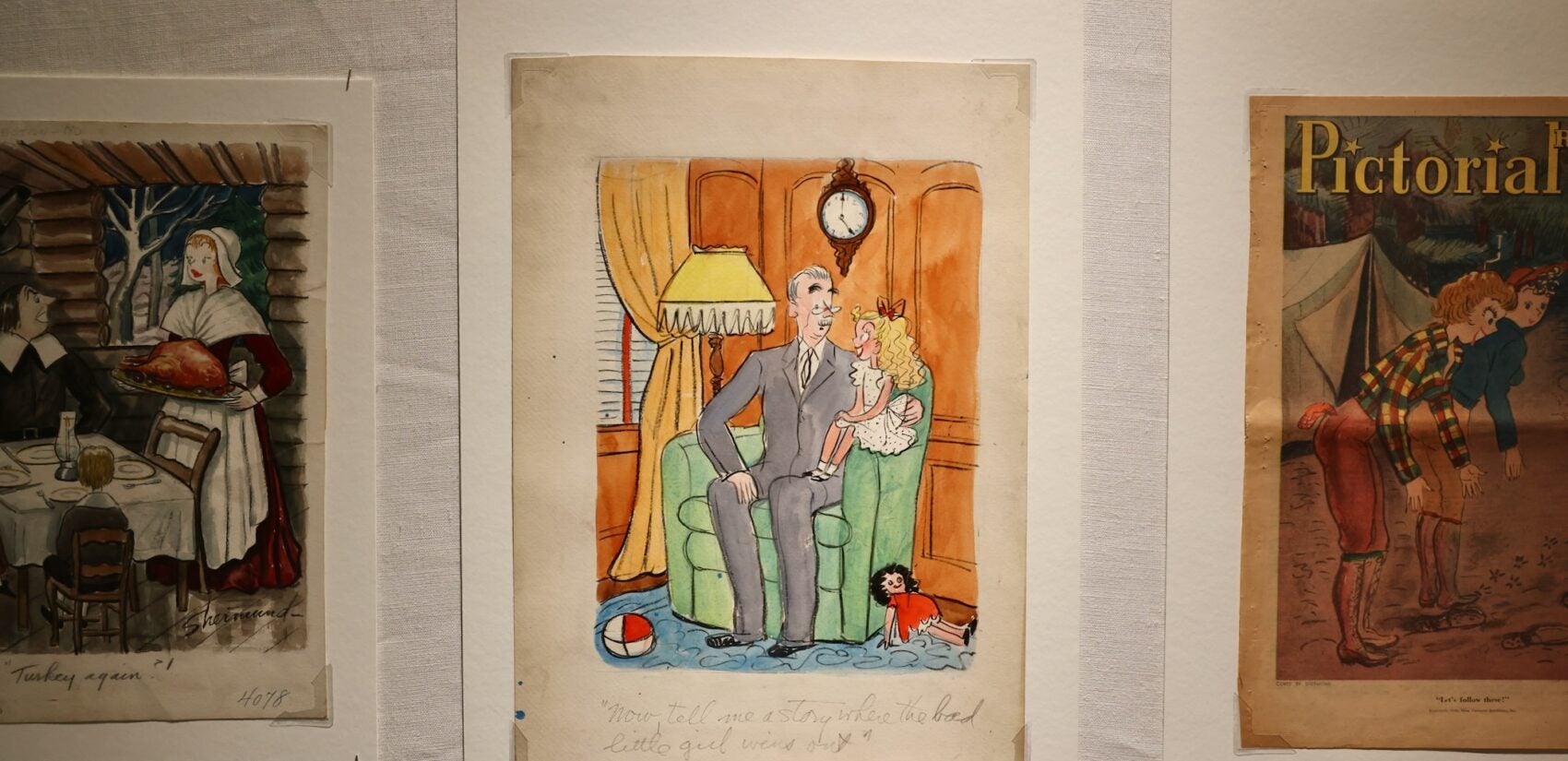

Shermund’s penchant for impolite femininity is where the title of the exhibition gets its name: “Tell Me a Story Where the Bad Girl Wins: The Art and Life of Barbara Shermund.” It is also the title of the newly published biography by curator Caitlin McGurk.

McGurk said Shermund was exactly what founding editors Harold Ross and Jane Grant needed to make the kind of magazine they had envisioned.

“Back then, most magazines had national syndication. So in order to have readers pick up your magazine anywhere in the country, you have to appeal to a broad audience,” McGurk said. “The New Yorker was one of the first magazines created to appeal to a very specific type of audience. Their thought initially was an audience of New Yorkers, but it occurred to them that there were people all over the world with a metropolitan mindset.”

“Barbara was one that really nailed it from the jump,” she added.

Shermund’s take on the lives of modern women was global. The wall text of the exhibition states she was the most well-traveled of the New Yorker cartoonists, which could drive her editors nuts: She traveled so much that she often had no permanent address, filing cartoons from hotel rooms and making it difficult for the magazine to track Shermund down.

McGurk first stumbled upon Shermund’s work about 13 years ago in the archives of Ohio State University’s Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum, where she works as curator.

“I opened up a box one day, saw her artwork, thought for sure it had to be from the ‘60s or ‘70s because the humor was so contemporary and feminist and queer,” she said. “I was shocked to discover that, no, it’s from the late 1920s and early 1930s.”

Two women in a modern art gallery pondering a blobby-shaped sculpture: ”Of course it’s a woman — they don’t make landscapes in marble.” A shopgirl brightly asks a man browsing a perfume counter: “Does she like to smell strange?”

The free spirit lifestyle of her cartoons — where one young lady laments to another “I guess the best thing is to just get married and forget about love” — was in many way Shermund’s life. She never married or had children, proudly so by the tone of her cartoons.

After the death of her mother due to the flu pandemic of 1918, her father remarried a woman 31 years his junior and 8 years younger than his own daughter, causing an irreparable rift. The cartoons on view include several May-December couples, with the older gentlemen as the butt of the gag.

Shermund’s last cartoon for the New Yorker was in 1944. She continued to illustrate for major magazines like Esquire and LIFE, and in advertisements for clients like Pepsi-Cola and Frigidaire, but clearly without the freedom she enjoyed at the New Yorker. In the 1940s and 50s she had a syndicated newspaper cartoon, “Shermund’s Sallies.”

She ultimately retired to the Jersey Shore, in Sea Bright, “spending pretty much all of her time swimming and playing with her dogs,” according to McGurk. When she died in nursing care in 1978 at age 79 in Middletown Township, New Jersey, few noticed. She was cremated and her ashes remained on the shelf of a funeral home for nearly 35 years.

“No one ever picked her up,” said McGurk.

It took the diligent work of a distantly related descendant cold-calling funeral homes in the greater Monmouth County area in 2011 to discover Shermund’s cremains. After a GoFundMe campaign in 2019 to raise burial costs, the cartoonist was laid to rest in Northern California next to her mother, who had died a century earlier.

“This fundraiser was fueled by cartoonists and feminists and people from all over the world who just felt like this isn’t right,” McGurk said. “We have to do better by our artists, especially our women artists who deserve to be recognized.”

At the time of Shermund’s death in 1978, there was a general newspaper labor strike in New York City that shut down all the major papers in the city for three months. Her passing was never reported by the press until 2022, when the New York Times featured an obituary of Shermund as part of its Overlooked project, recognizing significant people whose deaths went unnoticed at the time.

“Tell Me a Story Where the Bad Girl Wins” will be on view at the Brandywine until June 1.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.