‘You are not alone’: A look at the rising trend of teacher ‘onboarding’

Consulting teacher Dana Singletary prepares a group of new teachers for the classroom during an orientation session at The Arts Academy at Benjamin Rush in Northeast Philadelphia. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Twenty or 30 years ago most rookie teachers would get a textbook and a pat on the back before their first day in the classroom. Today the process looks and sounds a lot different.

It’s a steamy summer morning in early August. Scott Gordon–CEO of the Mastery Charter School network–strides up and down the aisle of a packed school cafeteria in Germantown. About 250 teachers stare back at him from long laminate tables. Each of these teachers started with Mastery about 10 minutes ago. It’s been an intense 10 minutes.

“About one in ten kids who enter kindergarten will actually go on and get a bachelor’s degree,” Gordon says, pointing to a slide stuffed with grim statistics about the educational landscape in Philadelphia.

He pauses. A vacuum silence envelops the room, interrupted only by the the squeak of Gordon’s leather shoes as he paces.

“ONE in ten.”

For 15 years Gordon has delivered a version of this talk. It’s the first thing new hires hear when they arrive at Philadelphia’s largest charter chain. And it’s more sermon than welcome–complete with brimstone, and fire.

“So for Mastery, the house is on fire,” Gordon says about 15 minutes into his talk. Behind him a projector screen bears the image of a home consumed by flames.

“We have a generation of young people who are fundamentally not getting what they need.”

Now if you have strong opinions about public education you’re probably either pumping your first right now or rolling your eyes. But set those emotions aside for a second, and imagine that this is just any company. And the head of this company is telling all of his new employees that the world they’ve just inherited is in crisis. And now ask yourself: Why?

“Mastery was founded with a purpose, to address a problem that public education is not working for all kids,” Gordon says later in an an interview. “So starting out day one that we have a problem, that young people are not getting what they need and we’re here to address that problem–that’s the most important thing.”

Among Mastery employees that house-fire metaphor in particular has become part of the company’s internal short-hand.

“They refer to themselves as the firefighters,” says Courtney Collins-Shapiro, Mastery’s Chief Innovation Officer. “Like my job is to put on the gear and get in here and make a difference for kids.”

Gordon’s speech kicks off a five-day orientation Mastery holds every year for new teachers. Mastery prides itself on introspection and evolution, but new teacher orientation is among a handful of yearly rituals that Gordon considers “non-negotiable.” In 2016, Mastery’s new teacher orientation cost the organization about $310,000–most of that tied up in teacher salaries.

“I think we look at great organizations–school districts, hospitals. They start with the fundamental why are we here,” Gordon says.

In the business world, employee “on-boarding” has long been a source of discussion and study. Schools, however, are only starting to catch up. Thirty years ago, new teachers could expect a textbook and a hearty pat on the back before their first day in the classroom, says Richard Ingersoll, a University of Pennsylvania professor who has studied the growing phenomenon of so-called “teacher induction.”

“The predominant thing was what we call the sink or swim model,” says Ingersoll. “Some would swim and some would sink. And you’re really quite isolated.”

Today, though, more and more schools are thinking about how they communicate to–and work with–new teachers. Most educators won’t hear a speech like Gordon’s or participate in a five-day workshop. But the days of simply showing up are over.

According to Ingersoll’s research, about 9 in 10 new teachers get some sort of targeted help. Sometimes that’s as simple as regular chats with the principal. In other cases it’s more extensive assistance, such as a long-term mentor, reduced class load, or classroom aide.

In 2012, Ingersoll and a pair of researchers reviewed the available literature on teacher induction and found that new teachers who receive extra help tend to perform better in the classroom and are less likely to leave the profession. The magnitude of the effect, however, varies widely depending on the level of support.

“You kind of get what you pay for,” says Ingersoll. “If the induction program is on the thin side the outcomes don’t look quite as good. But if it’s more comprehensive over a longer period of time–like a couple years of support–then there’s larger improvements.”

There’s no specific research, Ingersoll says, on the usefulness of new teacher orientations. That, however, hasn’t stopped them from proliferating.

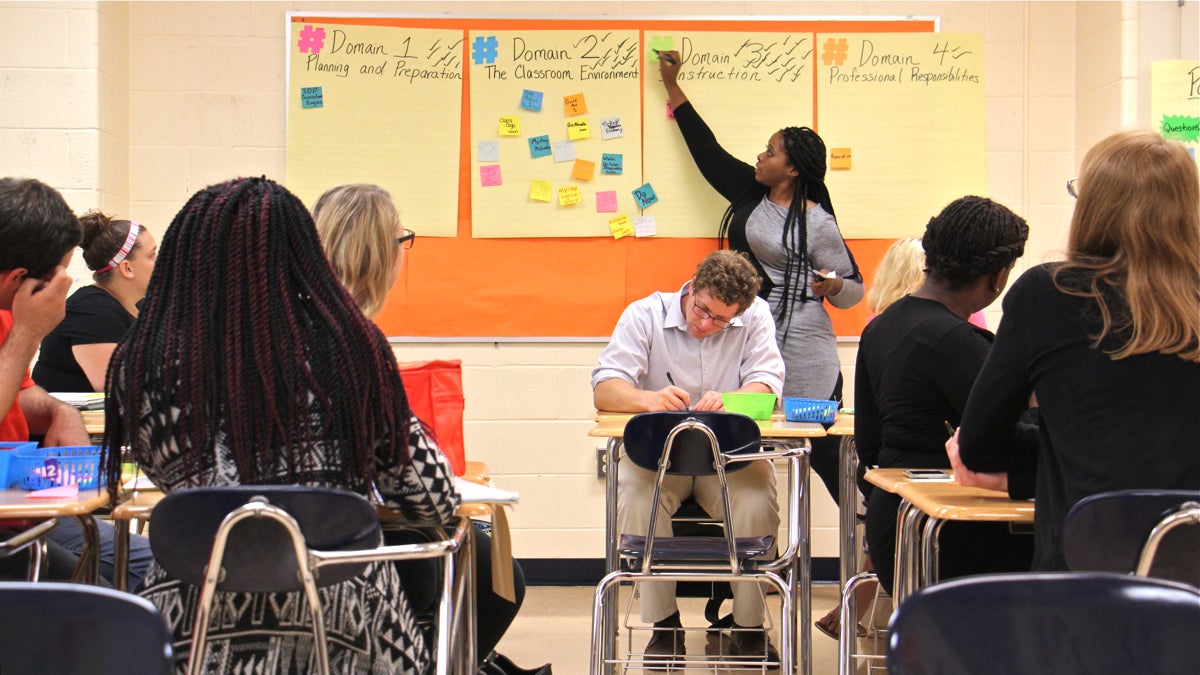

New teachers participate in a training course at the Arts Academy at Benjamin Rush in Northeast Philadelphia. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

New teachers participate in a training course at the Arts Academy at Benjamin Rush in Northeast Philadelphia. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

The School District of Philadelphia is a prime example. When Meredith Mehra began as Philly teacher in 2005 she went through a one-day orientation dedicated mostly to processing paperwork. As recently as two years ago the district’s orientation lasted three days, was largely unadvertised, and drew about 50 teachers.

This year, however, Mehra has revamped the entire program. As executive director of the district’s office of teaching and learning, she’s extended the orientation to five days and hustled to boost attendance. About 85 percent of new hires showed up, which this year equated to more than 500 teachers and a bill to the district of over $1 million.

When those 500 newbies arrived in August they–like their Mastery peers–were greeted with a speech. In this case the speaker was district superintendent William Hite.

“I want to stress that you are not alone as you begin at a new school,” Hite told the teachers, according to a transcript provided by the district. “Your time at orientation is an opportunity to establish a strong professional network with the School District of Philadelphia.”

As those comments would suggest, the district’s orientation focuses less on building culture and soliciting buy-in than it does on actual orientation. In other words, Mehra wants to make sure teachers don’t feel disoriented or isolated in the sprawling maze that is Philadelphia’s education system.

“You’re coming into a large district and there is so much in terms of systems and people that you don’t know,” she says. “And it creates apprehension. And that translates to your students.”

To mitigate that, parts of the district orientation get deep into the weeds. One session, for example, focuses on something called the Danielson framework, a jargon-saturated rubric the district uses to guide its teacher evaluations.

But there’s a healthy portion of bonding time, too. At the end of every day teachers gather in the same groups of 30 to talk about the job and the challenges they were about to face together.

“There’s gonna be a day in January where it was dark when you got up in the morning and it was dark when you went home and you may need to reach out to a lifeline and say, ‘Hey, remind me why I do this so I can go back in tomorrow,’” Mehra says.

New teachers fill a classroom at the Arts Academy at Benjamin Rush in Northeast Philadelphia for an orientation session. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

New teachers fill a classroom at the Arts Academy at Benjamin Rush in Northeast Philadelphia for an orientation session. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Mastery’s orientation serves much the same purpose–though the means are different. Mastery wants to imbue teachers with a sense of purpose so strong it steels them against the inevitable hard times.

On the first day of the orientation teachers read Mastery’s nine core values aloud and discuss them in groups. In another breakout session they trade rumors they’ve heard about Mastery and charter schools. Current staffers then go around to each group and try to correct perceived misconceptions.

That’s not to say everything in the orientation is about Mastery–far from it. The are sessions on classroom management, cultural competency, and pedagogy. There’s also a hefty chunk of time dedicated to team-building. Participants spend almost all their time grouped with those they’ll be working alongside in the fall.

Over the past couple years, Mastery’s teacher retention rate–or the number of teachers who return in a given year–has hovered just under 79 percent. Nationwide, roughly 85 percent of public school teachers stay at their school from year to year. Of course that comparison is hardly apples to apples since Mastery’s schools are almost exclusively in low-income, hard-to-staff urban areas. An internal study of 50 high-performing charter networks conducted by the Charter School Growth Fund–a venture capital firm that seeds charter expansion–found that Mastery “is in the top quartile in teacher retention.” The Charter School Growth Fund would not say where Mastery ranks in the top quartile or release any more details about the rankings.

When asked the School District of Philadelphia wasn’t able to provide its teacher retention statistics.

The coming school year, however, should test of the district’s on-boarding process. Thanks to a small budget surplus and aggressive hiring campaign, the district is incorporating a bumper crop of new staff. Whether they stay long term or not will certainly play a part in the district’s attempts to reestablish stability.

Alicia DeVane, who starts this fall as a middle school science teacher at BB Comegys School in Southwest Philadelphia, is still sizing up her orientation experience.

“It’s kind of like you know when you eat a chicken wing,” DeVane said during the third-day of teacher orientation. “You eat what you need to and you spit out the bone, the stuff that you don’t like.”

Some of the training on specific district protocols can feel abstract, she said. But she’s enjoyed meeting other teachers. It’s motivation–and a subtle reminder that she isn’t in this alone.

Chett Garcia has been searching for that kind of spark after a dispiriting year at a local Catholic school. Garcia, a six-year teaching veteran of the parochial school system, started his first public school job at Mastery’s Thomas campus in deep South Philadelphia this fall. Of the 256 new hires at Mastery’s orientation this year, only 32 percent are brand new to teaching. More than half–52 percent–have over two years of prior experience.

A fan of the education blogger and charter critic Diane Ravitch, Garcia brought a cautious outlook with him to Mastery orientation. He was especially wary of entering environment where, as he put it, you might have “drink the Kool Aid” in order to fit in.

After the first day of orientation, however, he felt more inspired than he did indoctrinated.

“I love how they try to say this is what we’re about,” he said. “And if you’re with us, this is what we’re about and we want you to be on board for that.”

That kind of collective focus didn’t exist at his old job, Garcia said. After more than half a decade in the classroom he needed a reminder of why he does what he does.

“It gives everyone a mission to kind of hold onto when the days get really difficult and you start to question why you do this job,” said Garcia. “Then you realize there’s all this “why.” The “why” is so important.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.