N.J. wants more cops trained to spot stoned drivers. Critics question the science behind methods

Hundreds of police officers in New Jersey are trained to recognize signs of driving under the influence of drugs. But some question whether their assessments are scientific.

Listen 4:59

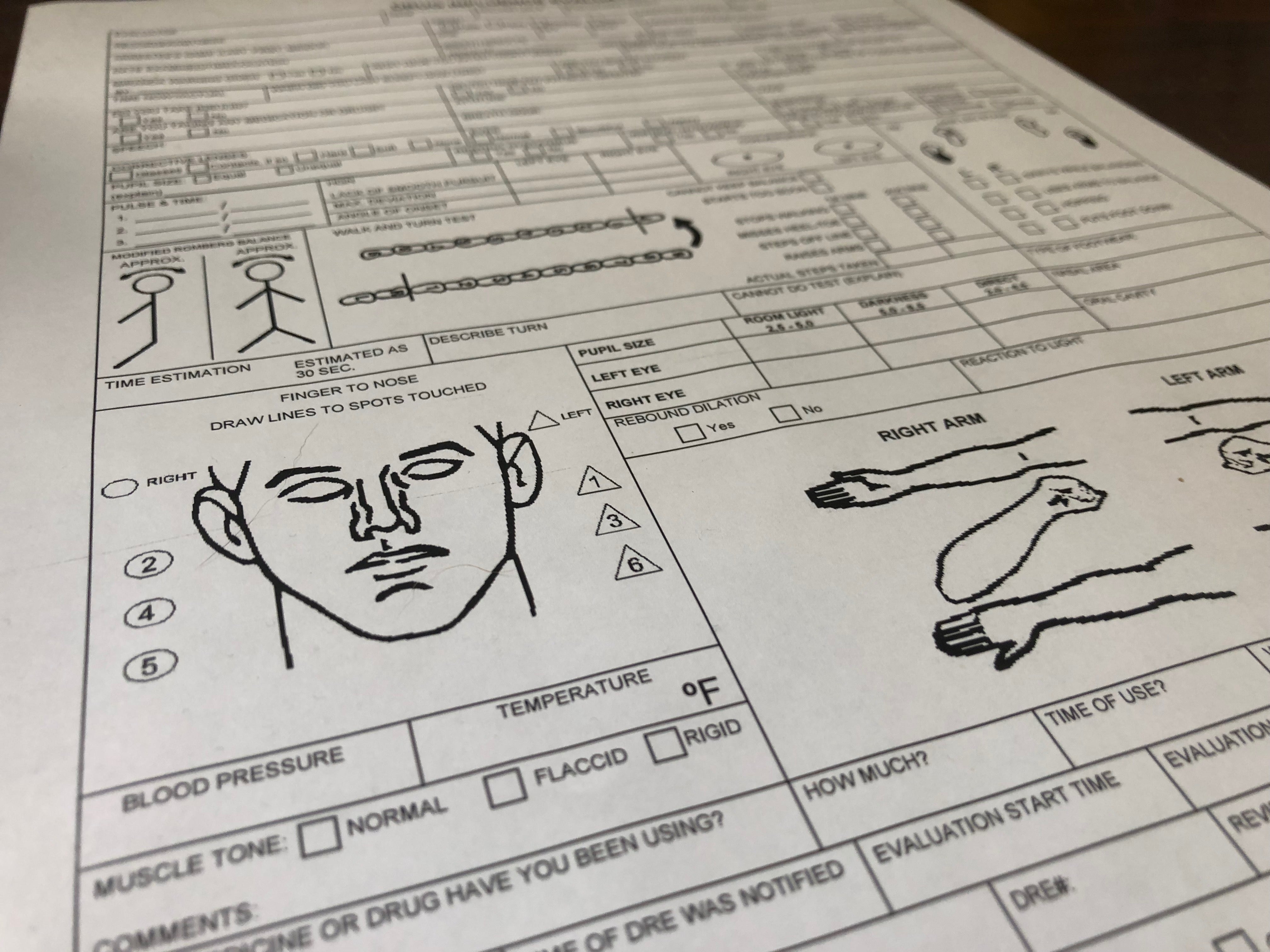

Hundreds of police officers in New Jersey are trained to recognize signs of driving under the influence of drugs. But some question whether their assessments are scientific or subjective. (Lenny Ignelzi/AP Photo)

Droopy eyelids. Dilated pupils. A racing pulse.

More police officers in New Jersey will be on the lookout for these symptoms in drivers, as the state prepares to dramatically increase the number of police specially trained to spot people under the influence of drugs.

It comes as top state lawmakers consider legalizing recreational marijuana, which law enforcement officials predict would lead to a surge in the number of drivers getting high before getting behind the wheel.

Yet the state’s plan to beef up its contingent of about 520 drug recognition experts, known as DREs, already the second-largest in the nation, has defense attorneys and criminal justice activists raising alarms about a methodology they say is flawed and should be barred from the courtroom.

“Some people call it junk science. Some people call it nonsense,” said Remi Spencer, a criminal defense attorney based in West Orange who specializes in driving-while-intoxicated cases.

Spencer said the DRE methodology is scientifically dubious, yet it has the power to send defendants to jail for months and revoke their driving privileges for even longer.

“When the state uses a [drug recognition expert] in a drug DWI case, the defendant is really not getting the benefit of a fair process,” she added.

But law enforcement officials warn that drugged driving would go unchecked without DREs, and they say criticism of the program stems from a misunderstanding their methods.

“If these defense attorneys or judges sat down and observed what we did, they would understand that, hey, this program does work,” said Sgt. Mike Kelly, a 16-year veteran of the Jackson Police Department and the incoming president of the New Jersey Association of Drug Recognition Experts. “This is getting people off the road who are dangerous and have issues but are not bad people.”

The debate over DREs in New Jersey is heating up just as the state’s top court prepares for the first time to hear a challenge on the scientific merits of the methodology.

The New Jersey Supreme Court is considering the case of a Denville man who was convicted of two DWIs based on drug recognition expert testimony in 2015, despite having a blood alcohol content below the legal limit.

Michael Olenowski argued that DRE methodology is scientifically invalid and should not be the only evidence used to convict someone of a DWI; so far, two courts have ruled against him and upheld the practice.

Opponents see the case as an opportunity to eliminate DRE from state courts once and for all. Meanwhile, its backers are angling to defend a law enforcement strategy they say is crucial to combat drugged driving and would be even more necessary if the state legalized recreational weed.

DRE on the rise

The drug recognition expert program was first devised in the late 1970s by a duo of Los Angeles Police Department sergeants who were looking for a way to deal with suspects they believed were impaired but who had a blood alcohol content below the legal limit.

“Two LAPD sergeants collaborated with various medical doctors, research psychologists and other medical professionals to develop a simple, standardized procedure for recognizing drug influence and impairment,” explains a section of the International Association of Chiefs of Police website.

The association later partnered with federal transportation officials to standardize the 12-step process that is used today by thousands of officers nationwide. That process includes taking a suspect’s vital signs, having them perform field sobriety tests, examining their eyes, and asking them a series of questions.

Because there is no legal limit for drugs in New Jersey as there is for alcohol, drug recognition experts are called in to evaluate whether a motorist is too high to be driving. Their testimony at trial is seen as crucial to securing drug DWI convictions in the absence of definitive lab tests.

New Jersey has more than 500 drug recognition experts — including New Jersey state troopers and local police officers — trailing only California.

State authorities plan to grow the force of drug recognition experts by offering more training sessions and upping the state’s current pace of certifying about 100 new DREs each year.

“We have been anticipating the Legislature and Gov. [Phil Murphy] acting on some form of [recreational marijuana] legalization for a period of time, so we’ve been ramping up our efforts to increase the number of DREs,” said Attorney General Gurbir Grewal at a recent Assembly Budget Committee hearing.

Lawmakers in March canceled a planned vote to legalize the drug, and it is still unclear whether there is enough support in the Legislature to pass the measure.

Critics question the science

As the state pushes ahead with a major expansion of its drug recognition expert program, opponents are amplifying their criticisms of a procedure they say is too subjective to be scientific.

“A DRE is basically like a coin flip,” said Kim Schultz, an attorney in the New Jersey’s Office of the Public Defender who has represented defendants accused of driving while intoxicated. “The ways that DRE evaluations are performed are different in every jurisdiction, whether they’re supposed to be or not.”

For example, one part of the evaluation requires the officer to examine a suspect’s muscle tone, because certain drugs can cause a person’s muscles to become rigid or loose and flaccid. But critics say there is no clear distinction between rigid, flaccid, and normal muscle tones — and that changes in muscle tones could be explained by causes other than drug use.

At the end of an evaluation, an officer is supposed to match symptoms observed in the suspect with several drug categories listed on a standardized grid used by DREs across the country. But skeptics say that symptoms can be misread or caused by other factors, and a suspect on multiple drugs may exhibit conflicting symptoms that are hard to interpret.

“We’re not talking about putting the results into a machine and having the machine spit something out,” Schultz said. “We’re talking about an officer injecting his subjective experiences into the observations of your client.”

Vito Abrusci, a former drug recognition expert with the Mendham Township Police Department and a former DRE instructor, agreed that evaluations can differ from one officer to the next.

“It does have some subjectivity that needs to be cautiously overseen,” said Abrusci, who now consults for DWI defendants.

Abrusci also raised questions about “confirmation bias” in drug evaluations. The drug recognition expert is typically called in after a patrol officer has already made an arrest, so part of the DRE’s evaluation is to speak with the arresting officer. That officer may tell a DRE that the suspect had admitted to taking certain drugs, or a suspect may tell the DRE directly. Doubters say that knowledge could color the DRE’s examination — intentionally or not.

“[A drug recognition expert] might be looking more closely for somebody to exhibit [certain indicators] if he knows that the person took [a certain drug], even if they say they took it last night before they went to bed,” Abrusci warned.

Abrusci added that, despite its issues, the drug recognition expert methodology plays a major role in stopping drugged drivers. “I still believe in the program, if it’s done properly. I think it’s important that the roads are safe,” he said.

One of the most common arguments against the DRE method is its use of the horizontal gaze nystagmus (HGN) test, in which an officer asks a suspect to follow a point from side to side with their eyes. If their eyes involuntarily twitch, that is a sign of impairment.

An appeals court in New Jersey found that the horizontal gaze test can be used by patrol officers to make an arrest, but it is not enough to convict. Yet the HGN test is part of the drug evaluation process, and that is regularly used in state courts to prove someone guilty.

“The courts are saying one thing,” said Schultz, the public defender, “and then, in practical application, it’s something different.”

A spokeswoman said the attorney general’s office would not comment on concerns with the DRE program. The New Jersey State Police did not respond to several requests for an interview.

DRE in court

On Feb. 13, 2015, Michael Olenowski was pulled over by a Denville Police Department patrolman for failing to wear a seatbelt.

The patrolman smelled the “odor of heavy alcohol,” according to court documents, and he asked Olenowski to perform several field sobriety tests, such as the one-leg stand, which Olenowski struggled to do. He was arrested on charges of driving while intoxicated.

In August of that year, police said, Olenowski drove his GMC Yukon off a Denville road and careened into a telephone pole. He was charged with another DWI, his third.

During the first arrest, Olenowski’s breathalyzer exam showed a 0.04% blood alcohol content, which is below the legal limit. He blew a 0.00% BAC during the second arrest. No urine or blood was taken for testing.

Nonetheless, Olenowski was convicted of drugged driving in both cases, due in part to the testimony of two separate drug recognition experts.

Olenowski appealed the two guilty verdicts, claiming that DRE testimony is unscientific and should not be used to convict a suspect. So far, lower courts have disagreed.

Superior Court Judge James M. DeMarzo, who first reviewed the appeal, upheld the convictions and suggested that the continued use of drug recognition experts by state law enforcement agencies was proof of its “general acceptance” by scientists, which means it can be used in court.

A three-judge panel in the state’s Appellate Division later wrote that testimony from a DRE was plenty to secure a drugged driving conviction and that corroborating urine or blood tests were not required.

“A defendant’s demeanor, physical appearance, slurred speech, and bloodshot eyes, together with poor performance on field sobriety tests, are sufficient to sustain a DWI conviction,” the judges wrote.

Yet defense attorneys argue that the courts have not done a thorough review of the science underpinning the drug recognition evaluations, so it is irresponsible to allow DREs to testify as expert witnesses in court.

Critics say permitting the officers to testify as expert witnesses at trial is no small matter given what is at stake for those convicted of DWIs in New Jersey: the temporary loss of a license and potential time behind bars.

“Most of the steps that the DRE is following in his or her evaluation offers circumstantial evidence to help support the conclusion that someone was using drugs,” said Spencer, the West Orange defense attorney. “To the state’s credit, it’s attempting to create an objective standard for these officers’ opinions, but, unfortunately, it’s not a very reliable standard.”

Olenowski’s appeal is now before the state Supreme Court. It is the first time the high court has taken up the issue of the scientific validity of the DRE methodology.

DRE on the defensive

“If you don’t have a DRE, a lot of these cases get dismissed,” said Sgt. Kelly, of the Jackson Police Department.

Backers of the drug recognition expert process argue it is the best way to prosecute drugged driving cases because toxicology tests only show the presence of drugs in someone’s system. They do not prove impairment. For example, marijuana may appear in the urine of someone who smoked three weeks earlier, but that individual would no longer be high.

“We’re showing impairment by the psychophysical and clinical [tests],” Kelly said, “not by what’s in the tox.”

If prosecutors cannot prove that a driver was impaired, Kelly said they may have to downgrade the charges to an offense like reckless driving, which carries more lenient penalties than a DWI conviction.

“Someone who is impaired by drugs gets into a crash, kills someone or whatever — they’re losing their license for 30 days,” if the charges were downgraded, Kelly said. “That’s why the DRE is here.”

To become a drug recognition expert, a New Jersey police officer must be recommended by a current DRE and have experience making drunken driving arrests before applying to the state police.

Aspiring DREs undergo 11 days of classroom training, take a series of tests, and conduct practice evaluations on volunteer subjects before they become certified. Current DREs must be recertified every two years.

After training and completing evaluations in the field, DREs are able to spot people high on drugs in the same way that the average person can recognize someone who is drunk, Kelly suggested.

“When you go into a bar, you know what someone under the influence of alcohol looks like. They have that smell, they’re stumbling, they’re falling, they’re obnoxious,” Kelly said. “It’s no different than drugs.”

Supporters of the DRE methodology say it is backed up by a series of validation studies that prove out its methods.

Backers point to three federally funded studies between 1985 and 1994 that showed a high degree of accuracy among drug recognition experts. In one study, Johns Hopkins University researchers found that DREs were 92 percent accurate in determining the drug category impairing a subject.

More recent analyses have looked at whether the symptoms used by DREs are accurate predictors of drug use. A recent study of Orange County, California, drivers with THC (the active ingredient in marijuana) in their blood found that a majority of subjects exhibited symptoms DREs are trained to look out for, such as an elevated pulse and droopy eyelids. It also found that just half of those drivers had elevated blood pressure, which DREs are also trained to correlate with marijuana use.

Kelly said drug recognition experts are trained to ignore admissions from suspects and base their conclusions on the 160 “observation points” present in the standard DRE evaluation.

Yet critics maintain that these evaluations will never be foolproof as long as they remain at the discretion of individual officers, and they are hoping the New Jersey Supreme Court has the same view.

“I think it’s a dangerous path to go down,” said Schultz, the public defender, “and the more subjective power we give to officers, the more dangerous it will be.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.