Murphy calls for returning right to vote to felons on probation or parole

In State of State address, governor comes out publicly for controversial reform and seeks other ways to expand right to vote.

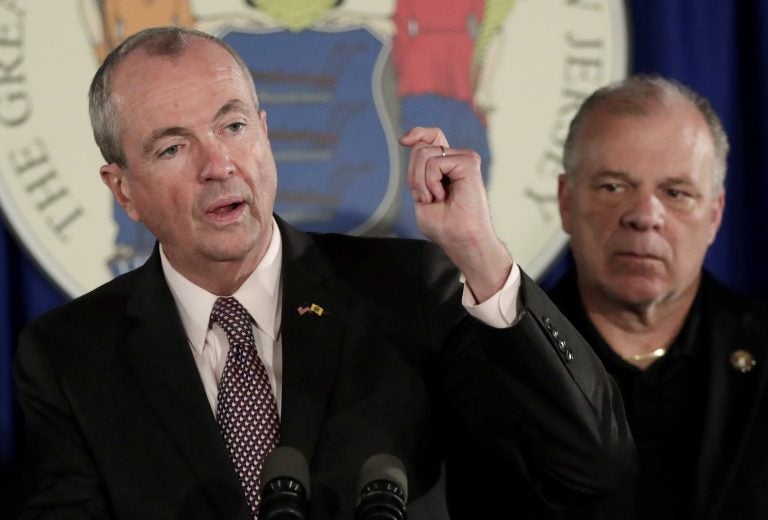

In this June 30, 2018, file photo, New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy, (left), discusses his state budget deal with Democratic legislative leaders, as state Senate President Stephen Sweeney, (right), listens during a news conference in Trenton, N.J. (Julio Cortez/AP Photo, File)

Gov. Phil Murphy wasn’t shy about patting himself and lawmakers on the back in his State of the State speech for making it easier both to register to vote and to cast a ballot. But he also wants to increase the number of registered voters by re-enfranchising felons on probation or parole, a controversial initiative.

This marked Murphy’s first public support for the concerted effort, launched last year by a number of progressive advocacy groups and legislators, to undo a 175-year-old law that strips the right to vote from those convicted of serious crimes until they have completed their entire sentence. But the governor stopped short of fully embracing legislation — embodied in S-2100 and A-3456 — that would return the right to vote to those who are incarcerated.

“Let’s open the doors to our democracy even wider,” Murphy said toward the end of his speech to a joint session of the Legislature on Tuesday. “Let’s restore voting rights for individuals on probation or parole, so we can further their reentry into society. And we further their reentry into society by allowing them to exercise the most sacred right offered by our society — the right to vote.”

During his address, Murphy also called for lawmakers to pass additional voter expansion measures that he backed during his campaign. These include:

- Allowing residents to register to vote online;

- Permitting Election Day registration at the polls;

- Letting 17-year-olds register and vote in the June primary if they will turn 18 in time for the November general election;

- Enacting “true” early, in-person voting statewide. But Murphy’s call for restoring voting rights to convicted felons on probation or parole is likely to be the most controversial of his efforts to expand voting. Republicans, certainly, were not enthusiastic, but it is the type of issue that could cross party lines.

Calling for change

Murphy’s call came a day after activists gathered in Trenton to push for a number of progressive priorities, including expanding the right to vote.

“We must continue the work of building an inclusive democracy in the Garden State by restoring the right to vote to nearly 100,000 people with convictions,” said Ryan Haygood, president of the New Jersey Institute for Social Justice. “The lesson to take from this important moment is that people who care about social and racial justice cannot afford to be timid. The heart of our democracy is at stake.”

The institute has been at the fore of the push, releasing a report last February that showed more than 94,000 New Jerseyans — 87 percent of them not in jail but on probation or parole — cannot vote as a result of the 1844 law. More than half of the disenfranchised, or about 47,400 people, were African-Americans.

Murphy’s support for restoring the vote to that 87 percent drew applause from the crowd in the Assembly chamber, but also some head-shaking by a few Republicans. Following the speech, Assembly Minority Leader Jon Bramnick (R-Union) said this effort should not be one of Murphy’s priorities and voiced his own opposition to the idea. “Whether you agree with that or not, clearly, I don’t believe that that’s one of the priorities for the voters and the residents of the state of New Jersey … for the people who are trying to put food on the table,” he said. “I would have some concerns that until you’ve completed your entire sentence … including probation and parole. At that point, the person has met all the requirements by the law.” Until then, Bramnick continued, “you’re still under the supervision of the courts or probation, which indicates you haven’t completely paid your price to society.”

Too high a price

Supporters for re-enfranchisement argue that there’s no reason why losing the right to vote needs to be a part of the price a person must pay, and it is under lawmakers’ control to change that. Currently, all those convicted of indictable offenses lose the right to vote until they complete their entire sentences, which include probation or parole. Such offenses range from being charged as a minor for marijuana distribution or shoplifting more than $200 in merchandise to rape or murder.

It had been common throughout the country for states to strip felons of their voting rights, sometimes forever. More recently, however, states have been reinstating these rights to some degree. According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, felons never lose their right to vote in two states — Maine and Vermont. In 14 other states and Washington, D.C., felons cannot vote while incarcerated but are automatically re-registered upon release, including while on parole. The laws in 21 other states are similar to New Jersey’s. In the remaining 12 states, felons have an additional waiting period, have to seek gubernatorial or court approval to vote again, or may never be able to vote again for convictions for the most serious offenses.

Legislative sponsors and advocates view restoring the vote here as a civil rights issue. Blacks in New Jersey are affected disproportionately by the current system because they make up such a large portion of the prison population. Although African-Americans account for just 15 percent of New Jersey’s overall population, they represent about half of those who have lost their voting rights as a result of a criminal conviction, according to the NJISJ report. More than 5 percent of New Jersey’s voting-age African-Americans have been denied the right to vote by the law.

Backing changes to the law

The effort to change the voting law has the support of about 80 organizations. Groups like the institute hold the position that voting rights should never be taken away for a crime, thus allowing prisoners to continue to vote while behind bars. An inmate would vote by mail using the address where he lived prior to incarceration.

Murphy spokesmen did not return a request for comment on whether the governor might also support allowing felons to vote while still in prison, which he did not expressly state. Neither the institute nor the American Civil Liberties Union of New Jersey responded to the question of whether they would back the re-enfranchisement of those on parole and probation if it did not also apply to those still incarcerated.

Sen. Sandra Cunningham (D-Hudson), a co-sponsor of the legislation to re-enfranchise felons, issued a statement praising Murphy’s call for action on the issue. The measure, introduced last March, has not had a hearing in either the Senate or Assembly.

“The incarcerated are among the most underrepresented population in the state. New Jersey already allows for former non-violent felons to vote, but we can do better,” Cunningham said. “New Jersey could become a leader in this country with this needed criminal justice reform. I look forward to working with him on this important issue in the near future.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.