Monumental matters in Philadelphia

Mural Arts Philadelphia’s temporary exhibition, Monument Lab: A Public Art and History Project, asks: “What is an appropriate monument for the current city of Philadelphia?”

In the wake of the white nationalist rally nominally organized to protest plans to take down a statue of Robert E. Lee in Charlottesville, Virginia that left one counter-protester dead and scores injured, citizens across the country are having conversations about monuments in public spaces.

New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio appointed an advisory commission to develop guidelines on how to address public art that is seen as “oppressive and inconsistent with the [city’s] values.” Baltimore Mayor Catherine Pugh said she would remove the city’s four Confederate monuments “quickly and quietly.” And she did under the cover of darkness.

The Pittsburgh Art Commission voted to remove the monument to Stephen Foster, the “Father of American Music,” who is memorialized with a barefoot slave seated at his feet.

In Philadelphia, calls to remove the monument of former mayor and police commissioner Frank Rizzo from the steps of the Municipal Services Building grew louder. Truth be told, the Rizzo monument has been controversial from day one. Tellingly, there was no pretense the privately-funded monument was for all Philadelphians. It was unveiled on January 1, 1999 after the Mummers Parade, which well into the 1960s officially featured clowns in blackface well into the 1960s and has continued to attract racial controversy even in recent years.

The monument’s association with the racially-charged Mummers Parade put an exclamation point on Rizzo’s legacy, which includes presiding over a police department whose practice of beatings “shocks the conscience.” That was the finding of the U.S. Justice Department which, in 1979, filed an unprecedented civil lawsuit against the city over its abusive policing tactics.

Public monuments should not be about nostalgists romanticizing a family member. The artwork was commissioned by the Frank L. Rizzo Monument Committee, which was spearheaded by Frank Rizzo, Jr. Many commentators have noted the parallels between Rizzo and President Donald J. Trump (here, here and here). Trump’s media bashing pales in comparison to Rizzo, whose loyalists picketed the Philadelphia Inquirer’s offices, effectively shutting the paper.

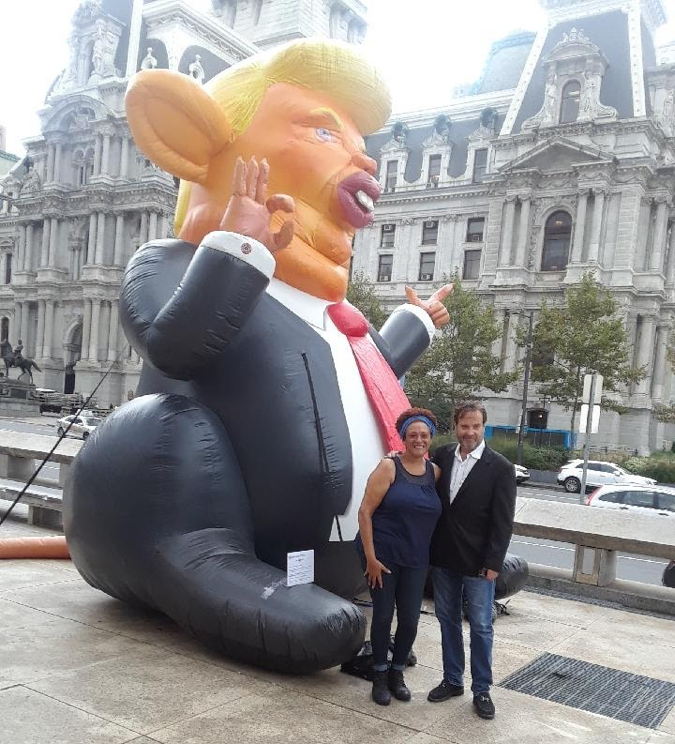

So, to underscore the absurdity of a monument to an old-school precursor to President Trump on Thomas Paine Plaza, I collaborated with New York City art dealer John Post Lee to bring his pop-up “Trump Rat” monument to Philadelphia on what would have been Rizzo’s 97th birthday.

Lee, who grew up in Philly during Rizzo’s reign of error, felt compelled to act. “The idea that anyone in my native Philly ever thought that there should be a statue of Frank Rizzo, Philadelphia’s mayor from 1972 to 1980, is astonishing,” said Lee. “He was, and remains, a human stain. If there is a statue of Rizzo, then we might as well have a statue of the inflamed Eagle fans who pelted Santa Claus with snowballs at Veterans Stadium.

“It’s high time that Philly’s biggest rat came face-to-face with the rat who now threatens the very norms and decency of American civic life. “

It bears remembering that Philadelphians were never given an opportunity to weigh in on whether Rizzo deserved to be honored in a prominent public space. So, when the city recently issued a call for ideas, the people responded. Mine was among the 4,000 submissions to the Office of Arts, Culture and the Creative Economy. My comment reads, in part: “Public art is about public memory. Public art is not a history lesson; rather, it’s cultural memory that oftentimes sanitizes the past. The Rizzo statue romanticizes a person who left a legacy of police brutality, racism, sexism and homophobia, and was the subject of the first-ever mayoral recall effort. Public sculpture is not set in stone. Art Commission regulations anticipate that evolving community sensibilities may require the removal or relocation of an artwork.”

The City agreed that no public art is forever. It recently announced the Rizzo statue will be removed from Thomas Paine Plaza. “Earlier this year we initiated a call for ideas on the future of the Rizzo statue,” Managing Director Michael DiBerardinis said in a written statement. “We carefully reviewed and considered everyone’s viewpoints and we have come to the decision that the Rizzo statue will be moved to a different location.”

I tuned in to Dom Giordano’s talk show to hear what Frank Rizzo, Jr. had to say. He didn’t mince words. “It’s a sad situation. When that monument was created, it was created with that site in mind,” said Rizzo. “We were told that the Art Commission would have hearings. I’m prepared for those hearings. I got legal counsel prepared for those hearings. And then this statement comes out on Friday late in the afternoon kinda pulls the rug out from everything that we were told about process.”

Rizzo Junior’s lawyer, Joseph Q. Mirarchi, subsequently posted on Facebook that he has asked for a public hearing before the Art Commission and filed a right-to-know request.

I, too, want a public hearing. It would bring long overdue transparency about why then-Mayor Ed Rendell approved the installation of a pay-to-play monument on the steps of the Municipal Services Building. While Rizzo Jr. doesn’t “see the reason to even move it,” I don’t see the reason why it’s even there. The collective memory of Rizzo is that of a mayor who lorded over a city in decline. So it is incumbent upon those who want to maintain the status quo to tell us what Rizzo did to warrant this singular honor.

Rizzo nostalgists say he was a product of his time. If so, the question then becomes: Is a statue of a polarizing politician who urged his supporters to “vote white” an appropriate monument for a changing Philadelphia?

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.