Modern movie sound was born in a Philadelphia basement

Listen

Engineers and musicians set up on stage at the Academy of music in Philadelphia in 1939, to record music for the 1940 film Fantasia. RCA's John Volkmann is pictured in the lower right, facing the camera. (Courtesy of Jesse Klapholz)

Flipping through old, behind the scenes notes on Disney’s ‘Fantasia’, one audio engineer saw the start of surround sound.

When Jesse Klapholz discovered a faded folder labeled “Fantasound” in the piles of discarded, archived materials from the late audio engineer, John Volkmann, he gave pause. Volkmann was the “top guy,” as Klapholz described him, at RCA, the recording and electronics pioneer company.

The detailed notes and handwritten diagrams from Volkmann outlined the development of sound for the film “Fantasia.”

It all took place in the late 1930s.

“It was just so fascinating,” said Klapholz, a semi-retired audio engineer based just outside of Philadelphia. “I discovered America when I saw the folder.”

He stayed up all night looking through it.

“Fantasia,” with its mischievously cute, wizard-hat-wearing Mickey Mouse character, has become a staple in family households (as have those tiny sugar plum fairies and prehistoric dinosaurs). But to Klapholz, a historian, collector, and former editor of the Journal of the Audio Engineering Society, the film represents a lot more: flipping through these behind the scenes notes, he saw the birth of surround sound.

“Fantasia” was “revolutionary” in its experiments with cinematic sound and recording technology, says Klapholz. The film planted the seeds for a sonic experience that is often synonymous with modern cinema, and it helped pave the way for multi-track recording techniques that have become staples in the field of audio engineering today.

Yet for Walt Disney to pull this off nearly 80 years ago involved recording experiments in a Philadelphia opera house, collaborating with one of the greatest (and most eccentric) conductors of all time, not to mention launching a movie roadshow that brought specially designed playback systems, weighing some 15,000 pounds, into select theaters.

Jesse Klapholz found this folder labeled Fantasound in a pile of miscellaneous archived materials. (Elana Gordon/WHYY)

Early experiments in sound and cinema

“Fantasia” was a big step. It was only a decade earlier, around the time of the first ever electrical recordings, that “The Jazz Singer” starring Al Jolson marked the shift from the silent film age into one of sound. This 1927 film was considered the first “talkie,” and one of the first, big attempts to synchronize prerecorded sound with the moving image on screen.

The effect didn’t always work. The film had to be played on one projector and then manually lined up with the audio, which had to be played on a separate one.

“If the film broke and you spliced it and you lost a foot, things got out of sync,” said Klapholz. “It was real kludgy.”

Klapholz says the recording itself would have been in mono at that time, with the musicians basically recording together all at once into one channel, and then the engineers balancing the sound levels and different microphones in real time. This would result in one flat sound that would then come out of one speaker behind the screen in the theater.

Heading into the 1930s, technology giants RCA and Bell Labs, especially, were moving the needle forward, experimenting with how sound was recorded and played back. Both companies had been teaming up, independently, with a cultural icon at that time: Leopold Stokowski, one of the most famous conductors of all time.

He led the Philadelphia orchestra, and he was a big innovator at that time. He was known for his fierce drive to find new ways to make music sound interesting. And he wanted to bring this music to the masses, not just the select groups who attended concerts. Working with RCA, in nearby Camden, he and the Philadelphia Orchestra produced the first stereo recordings of orchestral music. He brought the orchestra to radios, phonographs, and to film, occasionally conducting on the big screen himself in the film “100 Men and a Girl.”

“I love very much the cinema, I think it’s an immense and extraordinary medium,” Stokowski told the BBC in a 1972 interview. “I notice there are often hundreds of people who perhaps do not ever go to a symphony concert, so I had an idea not long ago, I would like to reach people, to play music for them.”

Stokowski was also known for his wild hair, hollywood romances, and strong personality. He wanted full control over every note and detail of how the music sounded.

A “recording lab” in an opera house

A lot of Stokowski’s stereo recording experiments with Bell Labs and RCA happened in the Academy of Music in Philadelphia. It’s a beautiful, Renaissance-style opera house, with plush red seats, a crystal chandelier, and gold leaf tiers of audience seating that are still in use today. Stokowski had turned the basement into a sort of recording lab that was full of equipment. Engineers and technicians from both Bell Labs and RCA worked down there independently of one another.

Sometimes, the orchestra didn’t even know what was going on below them.

In 1933, the orchestra famously – and knowingly – performed a concert at the Academy of Music that Bell Labs transmitted by telephone wire, to a live audience in Washington D.C. Stokowski was at the controls in D.C., overseeing the sound levels across three speakers for the audience there in real time.

It was through all of these recording experiments, and that of “100 Men and Girl,” released in 1937, that the foundation for Fantasound was laid, says Klapholtz, and more specifically, the ability to record and produce sound in multiple channels. Engineers started experimenting with doing this on optical film, which would better align with the pictures on screen.

A partnership with Disney

Walt Disney, meanwhile, a young filmmaker at that time, had been developing these popular animated shorts called Silly Symphonies that were scored to music back in California.

He was innovating with technicolor and optical film, which again, allowed for better recording and playback of sound with moving images.

The story goes that Disney’s path collided with Stokowski in 1937. The two had met up at a restaurant in California.

“I was doing this “Sorcerer’s Apprentice” with Mickey Mouse, and I happened to be having dinner with Stokowski, and Stokowski said ‘oh I would love to conduct that for you,'” Disney recalled in a 1963 CBC interview.

A partnership was forged. They went ahead and made the Sorcerer’s Apprentice out in L.A., with Stokowski directing the music. They went into it thinking of it as a standalone animated short, but realized along the way that they were on to something bigger.

“Disney said to me one day, ‘you know I like this so much, I’d like to make a long picture, bring in other things, so we discussed other music,” Stokowski later told the BBC.

“And before I knew it, I ended up spending 400 and some odd thousand dollars getting music with Stokowski,” Disney said, chuckling, in an interview featured on a Disney produced documentary about the film.

And so Fantasia, a film that would consist of several animated segments, was born.

Recording the film

They wanted to go all out.

“Disney was interested in a synergistic experience,” said John Canemaker, an academy award winning animator, writer and historian who teaches at New York University. “He wanted you to be convinced of the worlds that he was creating on the screen. He did it with the animation itself, the way it was drawn and timed, the way it looked and the style. And he also wanted it to effect you technologically.”

Disney had hoped to film it in 3D and present it on a wide screen. He even wanted to bring in smells, so audiences would be showered with scents of flowers or even gun powder during select segments.

This proved to be too big of a lift. He and Stokowski threw their energy into sound.

But how to make an orchestra sound bigger than life in theaters was a challenge.

“Technically, it was bad,” recalled the late Bill Garity, Disney’s chief engineer and studio manager, who oversaw Fantasound, in an interview with broadcaster Steve Cohen on WHYY in 1969.

Garity is referring to their first recordings of the “Sorcerer’s Apprentice” on Disney’s specially constructed sound stage in California.

“The principle problem was with 110 men in front of them, Stokowski couldn’t keep the orchestra together. The men in the back couldn’t hear what the men in front were playing,” he said.

Ultimately, they went to Philadelphia to record the Philadelphia Orchestra, who under Stokowski, knew how to create a rich sound in their home base, the Academy of Music. Stokowski, remember, had already turned it into a sort of recording lab.

“It was good for recording because you could add that [reverb] later,” Klapholz said.

(Others have contended that it was these acoustical challenges for live performances, which under the direction of Stokowski, made the Philadelphia Orchestra work harder, and in turn, shape their world renown sound at that time.)

Klapholz says the acoustics of the Academy of Music were also ideal for recording. The concert hall was notoriously dry and lacked reverb, or a reflection of sound that gives it a certain characteristic.

Disney’s engineering partner, RCA, was conveniently located in nearby Camden.

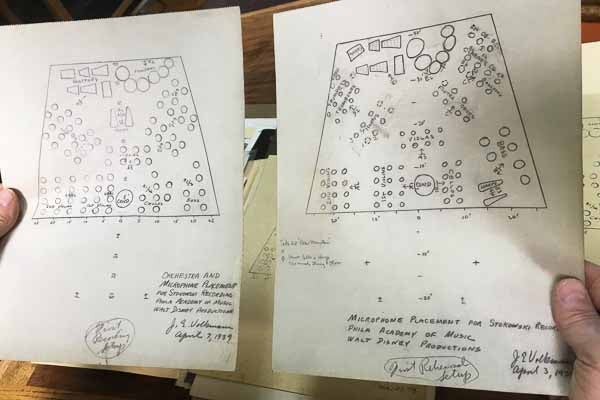

“The whole orchestra recorded at one time in Philadelphia,” said Klapholz, flipping through John Volkmann’s handwritten Fantasound diagrams for how the orchestra was placed on stage.

Nearly three dozen microphones were placed around the concert hall with different instrument sections recorded onto different tracks.

“So you could have strings on one, basses on another, percussion on another,” said Klapholz.

And below them, engineers and technicians filled the basement, following the music in real time, even muting or silencing microphones when their assigned section wasn’t playing.

And it was all recorded on highly flammable optical film in the basement.

“The fire marshall for Philadelphia didn’t allow them to have the library of films, the loading and unloading of film, inside the Academy. It’s a wooden structure,” said Klapholz. “So they had to do all that in mobile truck outside, which was not an RCA-identified truck.”

Klapholz says they would have wanted to keep a low profile of their big experiments.

Some soloists were recorded separately in California, still under Stokowski’s direction, in a process that’s ubiquitous in recording today: overdubbing. Klapholz says they did this with the help of a newer concept at the time: a separate recording channel known as the click track. It’s essentially a metronome, a “click click, tick tock” that keeps musicians playing in time with the orchestra recording. Disney studios had started using this technique over the last decade.

There was some tension during the whole process. Stokowski, supposedly, wanted the levels to be really loud at times, too loud for the recording equipment to handle.

Hand-drawn plans of microphone and orchestra placements. (Elana Gordon/WHYY)

Post production innovations in sound

That was the recording part. But Fantasound had another key element: post production.

“They had eight recorders going, and they just had a mixer, the mixer balances and combines signals together into three channels,” said Klapholz.

Klapholz says it was in this process that engineers developed a lot of behind the scenes sound techniques that are taken for granted today, that make sound move through space. That included multi track recoding and the development of devices that could control and balance sound levels. He says today, these devices like the “pan pot” are tiny and barely noticeable, but they were Rube Goldberg-type machines back then.

“This thing was incredible, it was put together with gears and bicycle chain sprockets,” he said, pointing to a picture.

But in order to pull this off, Fantasia needed one final thing: a special playback system.

“We had in mind, or Disney had in mind, that what is seen on the screen in Fantasia sometimes had motion, and that motion could be reproduced also for the listeners sitting in the theater,” Stokowski told journalist Steve Cohen in his 1969 public radio documentary.

A big roadshow

A lot of elaborate preparation went into making this work.

“The theater installation consisted of three loud speakers backstage and anywheres from 100 to 135 speakers around the sides to back of house,” said chief engineer Bill Garity, in that same documentary.

RCA and Disney had to design and then haul in special equipment to theaters because regular movie theaters wouldn’t have big sound systems in place. They worked on several versions.

Engineers rigged about a dozen places with the Fantasound system. It became a much hyped Fantasia roadshow. The equipment took up half a freight car, weighed 15,000 pounds, and cost more than 20,000 dollars a piece, according to Klapholz.

“It’s a lot. These were big heavy vacuum tube amplifiers,” he said. “It was quite an undertaking. Even by today’s standards.”

The basic Fantasound format involved four optical sound tracks on 35mm film. That included one control track and three channels of music. It was played on a special audio projector, directing sound around different parts of the theater, that was locked in with the projector playing the film. This was in part done through the system’s main feature, a tone-operated gain-adjusting device called a Togad.

Fantasia had its world premiere at New York City’s Broadway theater on November 13, 1940. It was a big red carpeted event. Attendees were taken to their seats by special Disney staff.

The New York Times wrote that motion picture history was being made.

Music pranced up and down the aisles, and boiled over the theater arches, as one paper wrote.

It all culminated with the eighth and final animated segment, featuring the music of Franz Schubert.

“We had a series of speakers in the back of the house which we switched manually for the Ave Maria bit,” Bill Garity recalled on WHYY.

On screen, appeared a cathedral-like forest. And then coming out of the speakers, it sounded as if “the orchestra played downstage center, choir was on either right and left and the soloist came in back stage, from the back of the house.”

People in the audience supposedly turned around in their seats, looking for the singer. On screen, a pre-dawn sky and a serene horizon would then fill with the colors of a coming sunrise.

“Well it got tremendous reactions and it sounded very, very exciting,” Disney’s recording supervisor, the late Robert Cook, said on WHYY in 1969.

“You’re in the middle of a giant orchestra,” Klapholz imagined. “It was designed to be able to be played as loud and with as much dynamic range from the softest notes to the loudest notes with complete clarity.”

During the early runs, the surround channels came on only during that last Ave Maria bit. Later refinements would remove some of the live mixing inconsistencies, according to Klapholz.

Time Magazine described Fantasia as stranger and more wonderful than anything Hollywood had done.

“It was way, way, way ahead of its time. That was stereo like there’s no stereo today,” Garity had said.

A film too ahead of its time

But Fantasia’s innovative success came at a cost.

“It’s stereophonic, high quality surround sound, that had never been done before. No other system could record, produce and play back that kind of thing, and so took well into the 60s for things to really catch up,” said Klapholz (The movie, Cinerama, influenced by Fantasia, would debut a decade later using stereophonic sound.)

Fantasia was a hugely ambitious leap.

“It was tremendous, and that’s why it just never caught on,” said Klapholz. “It was just too expensive.”

Fantasia, despite its revolutionary approach, was in many ways a bust. In that 1963 CBC interview, featured in a documentary about the film, Walt Disney described it as an artistic success but financial failure.

They couldn’t turn a profit with its limited and elaborate theater runs. The Fantasound system went into just a handful of regular theaters because movie theaters didn’t want to shut down while the system was installed. Only two places bought the system.

World War II was getting underway in Europe, cutting off box office sales there. Plus, the reviews were mixed.

“It’s one of the most radical commercial films ever made, and I think the reaction was strange when it first came out,” said Canemaker.

Music critics took issue with Disney putting cartoons, like Zeus throwing down thunderbolts, to serious works of music.

Ludwig van Beethoven’s Symphony No. 6 (“Pastoral”) was set to this cartoon. (via GIPHY)

Klapholz thinks that original Fantasound experience nearly 80 years ago would have been on par with cinematic sound today.

But he’ll never technically be able to know.

“It’s lost. It’s lost forever,” he said, referring to the original recording and playback systems.

That’s because technology has evolved. The playback systems proved to be too much for general movie theaters to adopt. During the 1950s, Disney re-released Fantasia, but in converting the original sound tracks to a magnetic film format, they ran the output over telephone lines.

“Deleterious effects snuck into it,” said Klapholz.

So in one sense, true Fantasound, as originally heard in theaters, is confined to the memories of those who back then, were lucky enough to experience it firsthand back in 1940.

But all is not lost. The soundtrack was restored in later releases, such as in 1990, further fixing any distortion. And Fantasia, despite those early snags, has turned into a film classic. It’s the subject of celebrations, remakes and updates, as recently as last year during its 75th anniversary.

The film has turned into an Xbox video game, where players get to act, as Stokowski did, as live mixers. And in other ways, one could argue, as Klapholz does, that movie-goers actually experience the legacy of Fantasound all the time: the film planted the seeds for a surround sound experience that has become a staple in theaters today.

Special thanks to Steve Cohen for coming to WHYY to digitize part of a WHYY 1969 radio documentary he produced about Leopold Stokowski. Excerpts were featured in this story.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.