How Philadelphia seniors are tracking microplastics in streams and working to ‘leave a better world’

Members of the Senior Environment Corps wade into streams, peer through microscopes and teach kids how to identify aquatic critters.

This story is part of the WHYY News Climate Desk, bringing you news and solutions for our changing region.

From the Poconos to the Jersey Shore to the mouth of the Delaware Bay, what do you want to know about climate change? What would you like us to cover? Get in touch.

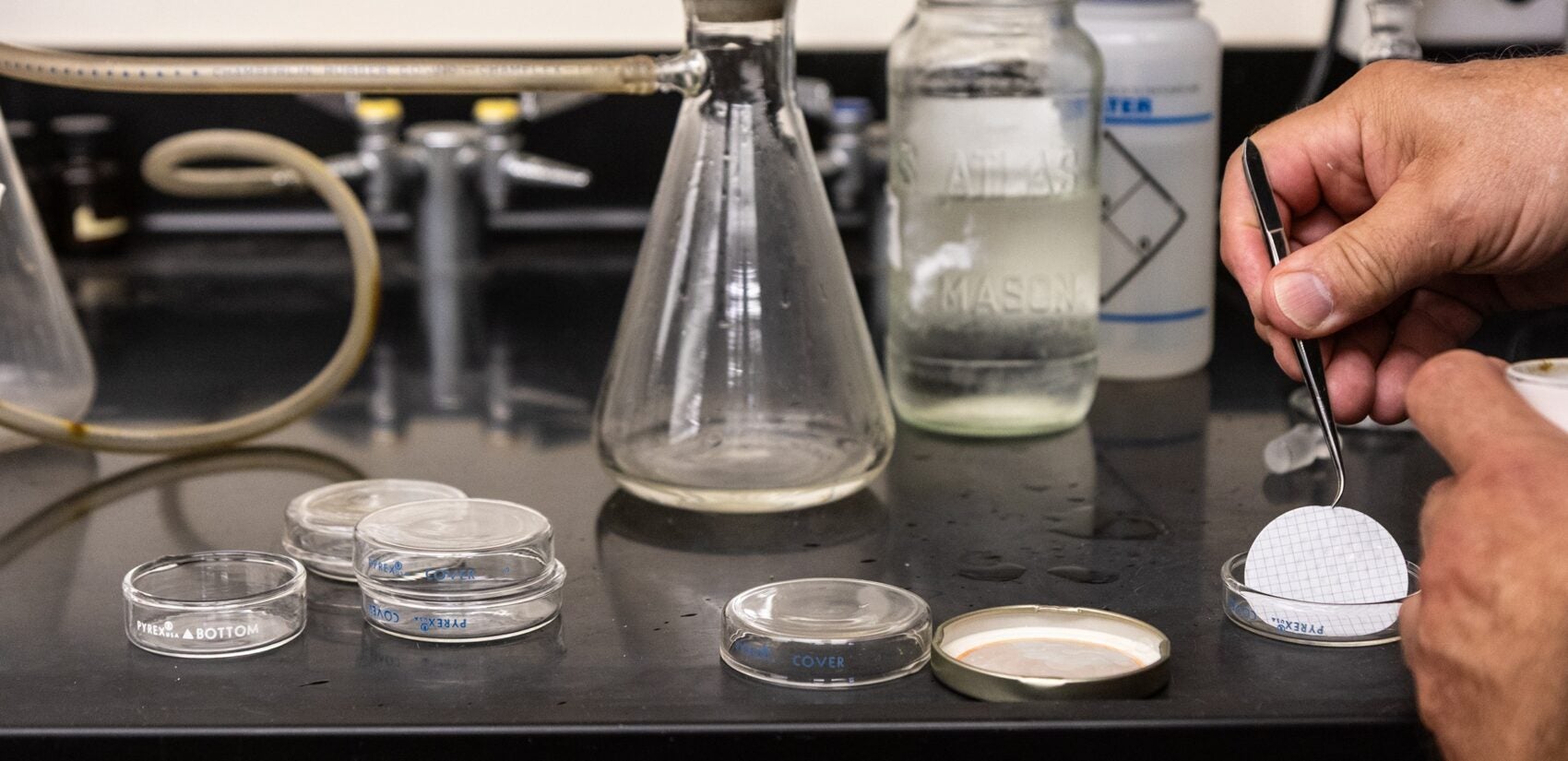

In a lab at Chestnut Hill College, Bob Meyer searches for tiny bits of plastic in a sample of water from the nearby Wissahickon Creek.

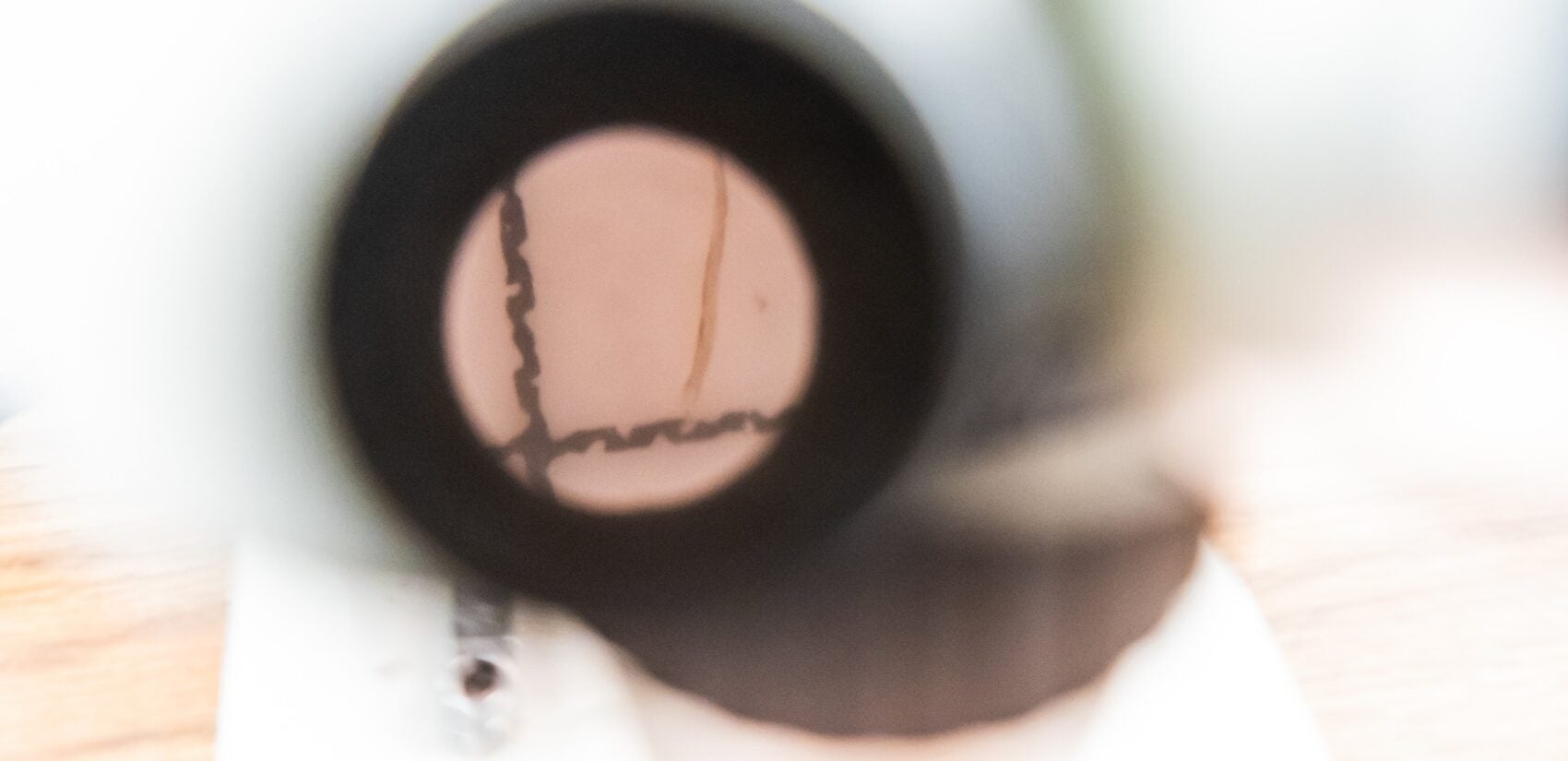

He draws the water through a filter to catch any microplastics that might be suspended in the sample. They’re too small to see with the naked eye, so Meyer places the filter under a microscope.

“There we go,” he said. “Got a thread. Yep, and it’s pink, so I know it’s plastic.”

Meyer, professor emeritus of biology at Chestnut Hill College, is part of a group of seniors who monitors air, soil and water quality in Philadelphia and the surrounding areas, called the Senior Environment Corps.

The group has been around for decades and is now collecting data on an emerging issue. Microplastics have been found in humans’ bodies, at the bottom of the ocean and in the Arctic. Scientists are still studying the risks that microplastics pose.

Meyer and another volunteer, David Schogel, tally up the bits of microplastics from the sample. They find jagged fragments, thin fibers and rounded nurdles — more than 40 pieces total from a few teaspoons of water.

“Lot of plastic,” Meyer said.

“And that’s just the first sample,” Schogel added.

The group is counting microplastics in samples of water from the Wissahickon Creek, upstream and downstream of the Ambler Wastewater Treatment Plant, to test whether the plant is affecting the concentration of plastic in the creek. They also found some microplastics in Philadelphia tap water collected in the lab at Chestnut Hill College.

“I don’t know how you get it out,” Meyer said. “I know how you stop it: You stop using plastic. But we’ll be pushing up the daisies before that stops.”

Staying busy and leaving a positive legacy

Meyer, 71, volunteers with the Senior Environment Corps because he wants to keep raising awareness about environmental issues — and stay busy.

“The horrible lure of retirement is to do nothing,” he said. “That’s no good because you just end up vegetating at home, watching daytime TV, and I don’t want to do that.”

The more than dozen volunteers keep active. Some wade into streams to collect water samples, while others test samples in the lab. Some teach kids how to identify aquatic critters and others do research.

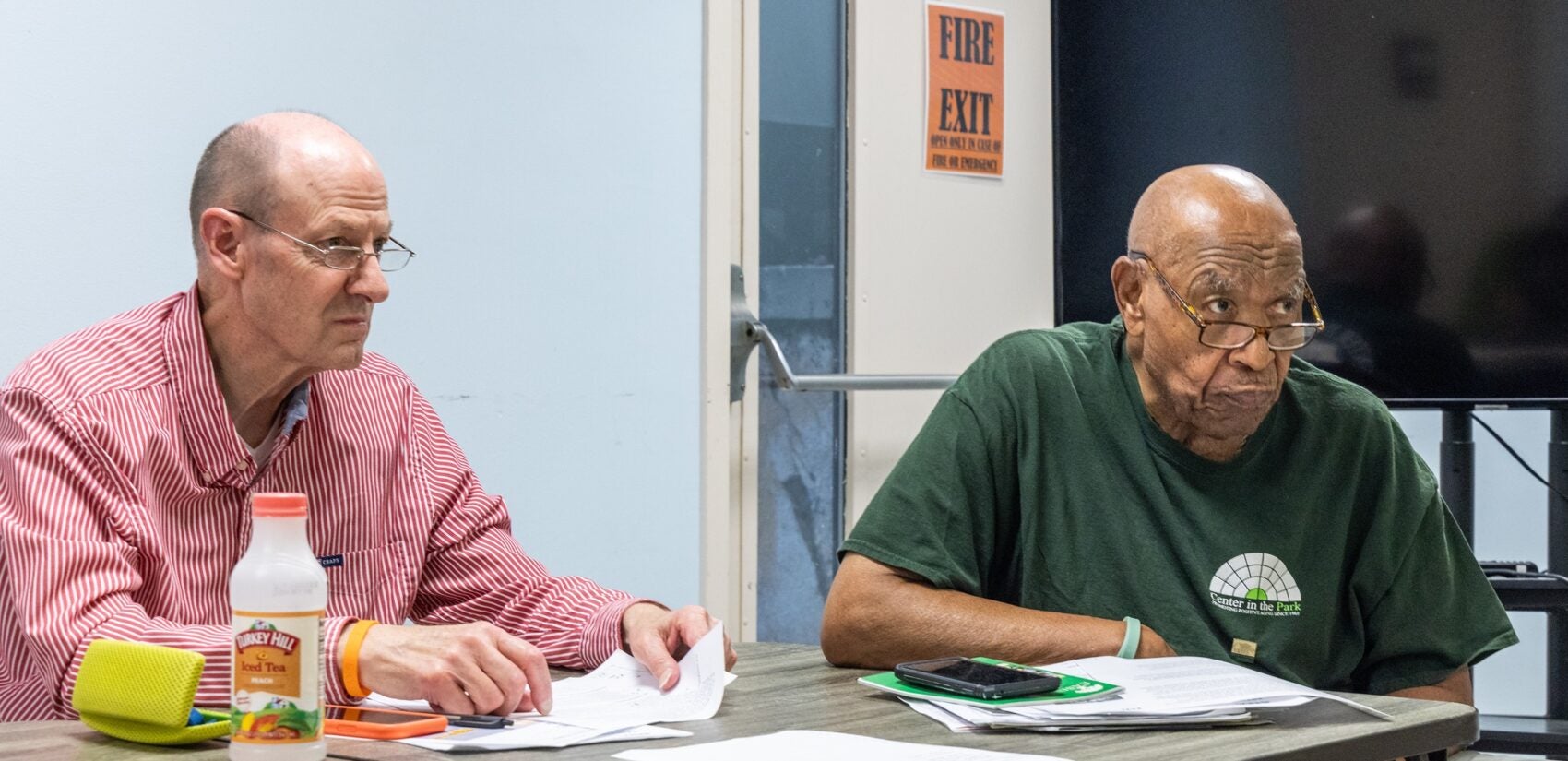

Meyer and Schogel say there’s a role for everyone, and the group is always looking for new members.

“If they’re breathing, we want them,” Schogel joked.

Schogel, 85, has been involved with the group for close to three decades. The retired social worker sees it as another way to leave a positive legacy.

“I’m not a wealthy fellow, and I don’t have any money to leave behind to any groups or even my family,” he said. “But I can leave a better world and hopefully inspire people to do something in the future.”

The group meets monthly at a senior center in Philadelphia’s Germantown neighborhood called the Center in the Park.

Eleanor Lundy-Wade, 74, retired from a career as a health inspector and educator. She thought her “biggest” activity at the center would be playing Scrabble, but was excited when she found out about the Senior Environment Corps.

“I said, ‘They’re seniors that love and do the environment?’” she said. “‘I want to be one of them.’”

Drew Brown became interested in the environment at age 12, after a counselor told him to stop playing in a creek at summer camp because it was polluted. Now 71, the Philadelphia Water Department retiree said that by monitoring creeks, the Senior Environment Corps could provide early warning to the people managing the city’s drinking water if they find signs of pollution upstream.

“Even though we’re retired, and we’re not being paid to do this, we can still be useful,” Brown said.

At 97, Fred Lewis is the group’s oldest member. He helped found it more than 30 years ago. Lewis retired from a career as a management consultant and sees the group’s work on microplastics as a way to bring attention to an emerging issue. He remembers when plastic first took off.

“We were all trying to find purposes for plastic,” he said. “It was something that was so new that people were just trying to get suggestions as to how we can take advantage of it. And now, it’s how we can end it.”

Lewis says some people might assume that the older you get, the less involved with society you become. But the Senior Environment Corps is proof that’s not always true.

“When you reach your age as being recognized as a senior, it’s certainly no indication that you’re on your way out,” Lewis said. “It possibly could be interpreted as, you’re on your way up.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.