Marking 50 years of struggle and a week of equality, Annual Reminders to march again in Philly

Listen-

Annual Reminder picketers march outside Independence Hall on July 4, 1965. (Photo courtesy of Temple Urban Archives)

-

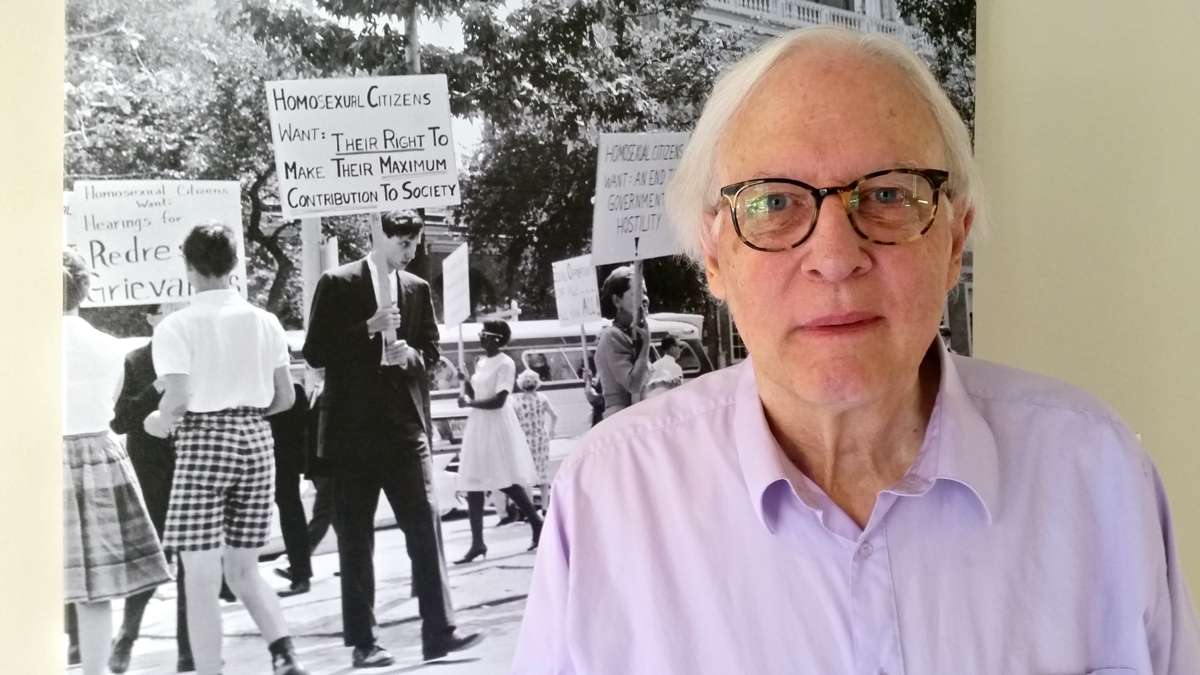

John S. James stands beside a photo of himself taken during the July 4, 1965, demonstration for gay rights at Independence Hall. (Peter Crimmins/WHYY)

-

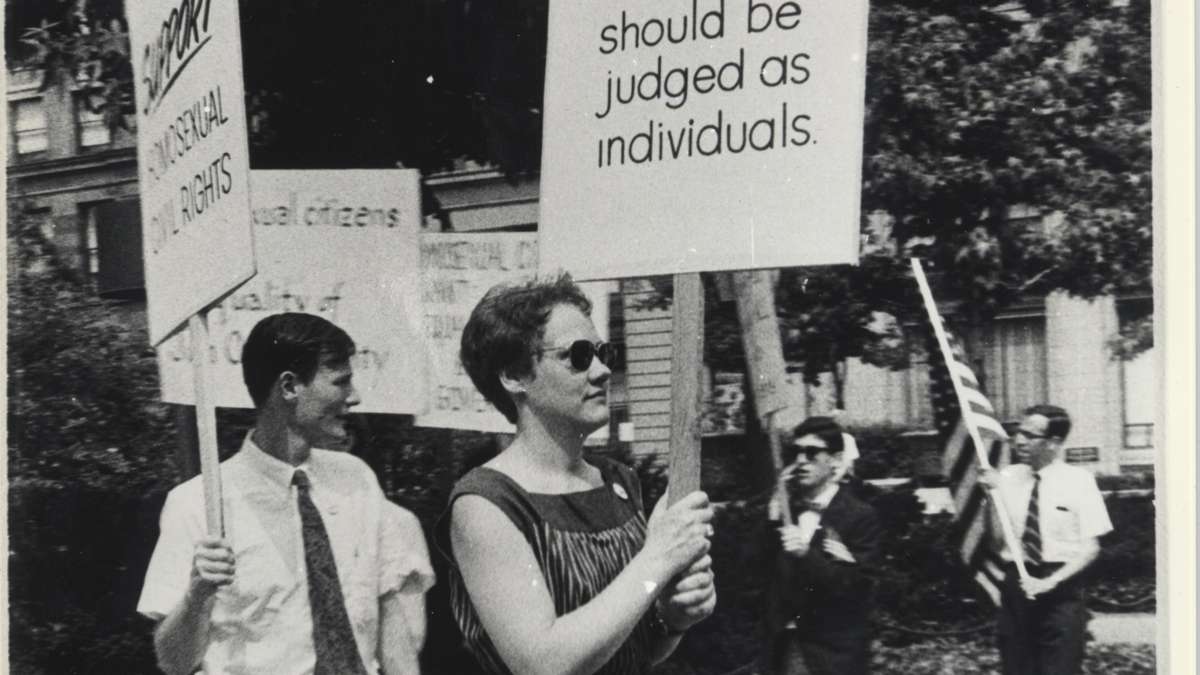

Barbara Gittings marches in the Annual Reminder in 1966. (Kay Tobin Lahusen/courtesy of the John J. Wilcox Jr. LGBT Archives)

-

Kay Tobin Lahusen, longtime partner of activist Barbara Gittings, chronicled the gay rights movement in Philadelphia with her camera. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

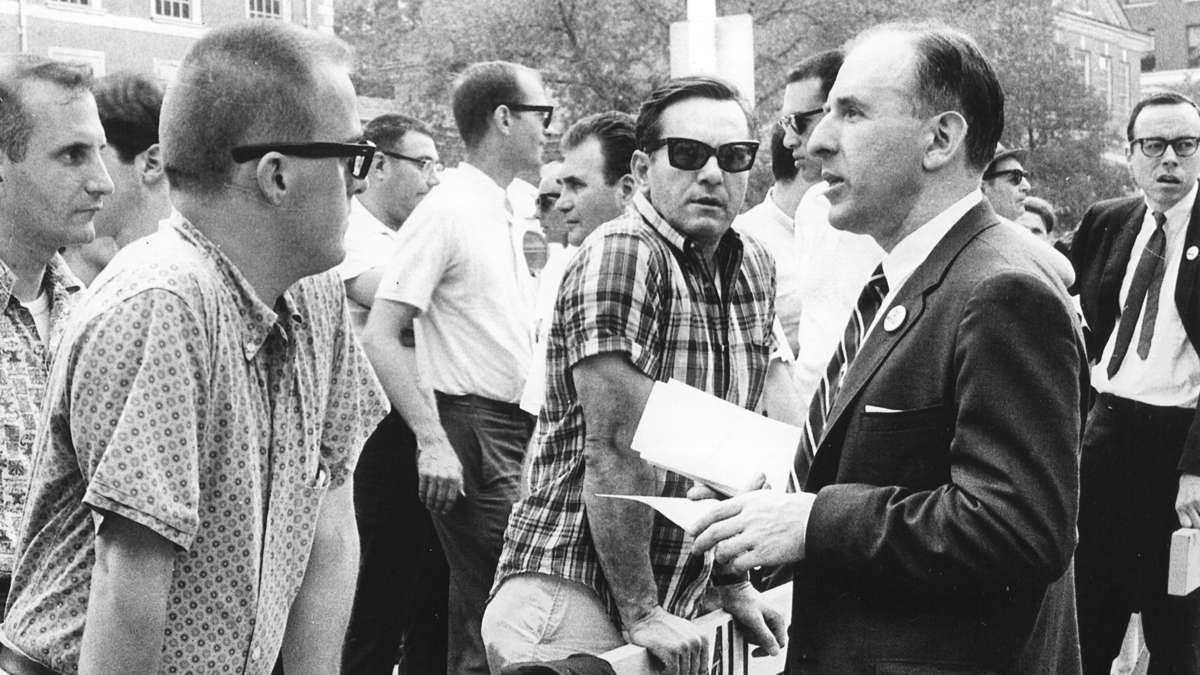

Gay rights activist Frank Kameny (right) at the 1966 Annual Reminder picket. (Kay Tobin Lahusen/courtesy of the John J. Wilcox Jr. LGBT Archives)

-

In the 1960s, while many gays declined to march in protests for fear of being recognized, Henri David threw lavish drag parties in Philadelphia. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

Picketers march outside Philadelphia's Independence Hall in what became known as the Annual Reminder for gay rights. (Kay Tobin Lahusen/courtesy of the John J. Wilcox Jr. LGBT Archives)

-

Marj McCann is a longtime gay rights activist in Philadelphia who, 50 years ago, refused to participate in the first gay right demonstrations in front of Independence Hall. The well-dressed Fourth of July picket was too risky. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

This Fourth of July marks not just the birth of America, but the 50th anniversary of demonstrations for gay rights.

Every year from 1965 to 1969, picketers known as Annual Reminders marched in front of Independence Hall in Philadelphia, calling for equal rights for homosexuals. This weekend, that demonstration will be re-created as part of a weekend-long anniversary celebration.

There weren’t many marchers at the beginning, only about 40, most coming in from New York and Washington. They were all told to look sharp – suits and ties for the men, dresses for the ladies. They carried signs announcing “Homosexual Americans Demand Their Civil Rights” and exhorting “Stop Cruel and Unusual Punishment for Homosexuals.”

“We used to say it was the message we carried, not we ourselves, that was important. But, of course, that was wrong,” said Kay Tobin Lahusen, an original picketer and life partner of its coordinator, Barbara Gittings. “Most people thought they had never seen a gay person. So it was important that we be on display, too.”

At the time, gays and lesbians were not allowed to work government jobs, at any level. The demonstrators were instructed to look employable.

These were not the first time gays and lesbians picketed. A year before, in September 1964, 10 people (a mix of gay and straight) picketed the U.S. Army Induction Center in New York to protest the Army’s ban on gay soldiers. (“We Don’t Dodge the Draft, the Draft Dodges Us.”)

Others followed, ranging from just four participants to two dozen, with very specific agendas: protesting a psychoanalyst who deemed homosexuality a mental disease or picketing the United Nations when Fidel Castro announced he would put homosexuals in labor camps.

The Philadelphia protests were the largest (by 1969, it had 150 participants) and the most broad, calling for equal opportunities, generally. “[America] has one large minority who are still not benefiting from the high ideals proclaimed for all on July 4, 1776,” Gittings told the Philadelphia Tribune in 1969.

‘We look like anyone else’

The pink and blue-striped shift dress Gittings wore for the protests is now on display at the National Constitution Center, in an exhibition of American gay rights activism.

Gittings organized the Annual Reminders with Frank Kameny, an activist in Washington, D.C., who had been fired from his job as an astronomer with the U.S. Army after being arrested for homosexual activity.

The arrest radicalized Kameny, who petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court to hear his case. It refused.

Kameny co-founded the Washington chapter of the Mattachine Society, a gay and lesbian activist group in many cities, with fellow activist Jack Nichols.

“We knew him as Warren. He was there under a pseudonym,” said John James, a Mattachine Society member and an original picketer in Philadelphia. “His father was an FBI agent, and J. Edgar Hoover really hated homosexuals. His father’s career or retirement could have been really messed up if Hoover found out that the son of one of his agents was a gay rights leader.”

The essential message of the Annual Reminders: We look like anybody else, so we should be treated like anybody else.

It was not a message everyone in the movement was behind.

Bravery or recklessness?

“It was a subject within the movement – were they nuts or brave?” said Marj McCann, an activist who in 1965 was a member of the Daughters of Bilitis, a lesbian group.

“Within lesbian society, the fact that we were pushing to not be stereotypes was threatening. It meant people couldn’t hide anymore. People were telling me in bars, ‘They think everybody who is gay looks like a diesel dyke. If you let them learn we look like everybody else, I’m in danger.'”

McCann attended the first picket in 1965, but not to march. She kept her distance to remain unseen.

“There was always something between me and the protesters — a tree or a phone pole, I don’t remember,” said McCann, who did not want to risk her job, family, or apartment in the event she might be seen in the company of known homosexuals. Her girlfriend at the time did not come out at all.

For some protesters, the risks were minimal because they were coming in from out of town. They weren’t recognizable by anyone in Philadelphia, and news traveled slow in 1965. The first demonstration was completely ignored by the press.

“I was the chronicler. How the hell do we have all these photos if I didn’t take them?” said Lahusen, 85, now living in in Kennett Square. “The movement was not taken seriously, even by gay people. Not only could they lose their jobs, but they just didn’t see themselves as going out in the street demonstrating.”

The quiet before the Stonewall storm

By the time of the first demonstration in 1965, President Johnson had begun the ground war in Vietnam. The American counterculture was staging large and loud anti-war demonstrations.

The Annual Reminders were distinct for being tame — and quiet. There were no chants, no confrontations, and – at first – no opposition. The picket occurred in late afternoon, after a major Fourth of July parade in Philadelphia, when spectators were tired and hungry. They were genuinely dumbstruck by the presence of homosexuals who appeared to be dressed for the office.

“People had been standing in the hot sun, had to go to the bathroom, get something to eat,” said Lahusen. “They were fed up with their Fourth of July. So we got out there, bravely, but hardly anybody was watching.”

The protests continued, quietly, for five years. The last one happened just a few weeks after police in New York raided a gay bar, the Stonewall Inn, which sparked a street riot. The Stonewall Riot was the flashpoint that future activism rallied around.

Gittings, Kameny, and other gay rights activists shifted their attention to New York, creating the Christopher Street Liberation Day.

“That was a major demonstration in New York that had vastly more people than all of our Reminder demonstration put together,” said James. “That was not about suits and ties at all.”

The whole idea of picketing had, by then, fallen out of fashion. Protest movements had gotten more brash, less fearful than the Reminders had been.

“Somebody had to get out and show their face in public,” said Lahusen.

The Christopher Street Liberation Day later became New York’s Gay Pride Parade — an event where participants are encouraged to be as extravagant as they want to be.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.