Lens: Finding Stonehouse Lane, South Philly’s lost neighborhood

A trip through the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin archives reveals detail on the otherwise lost neighborhood Stonehouse Lane, in deepest southeast Philly, where residents lived on the fringe of city life in semi-rural conditions into the mid-20th century. Hop in the wayback machine with Jake Blumgart:

It’s hard to imagine that South Philly was ever anything besides a great expanse of concrete and brick, with row homes stretching off to the horizon.

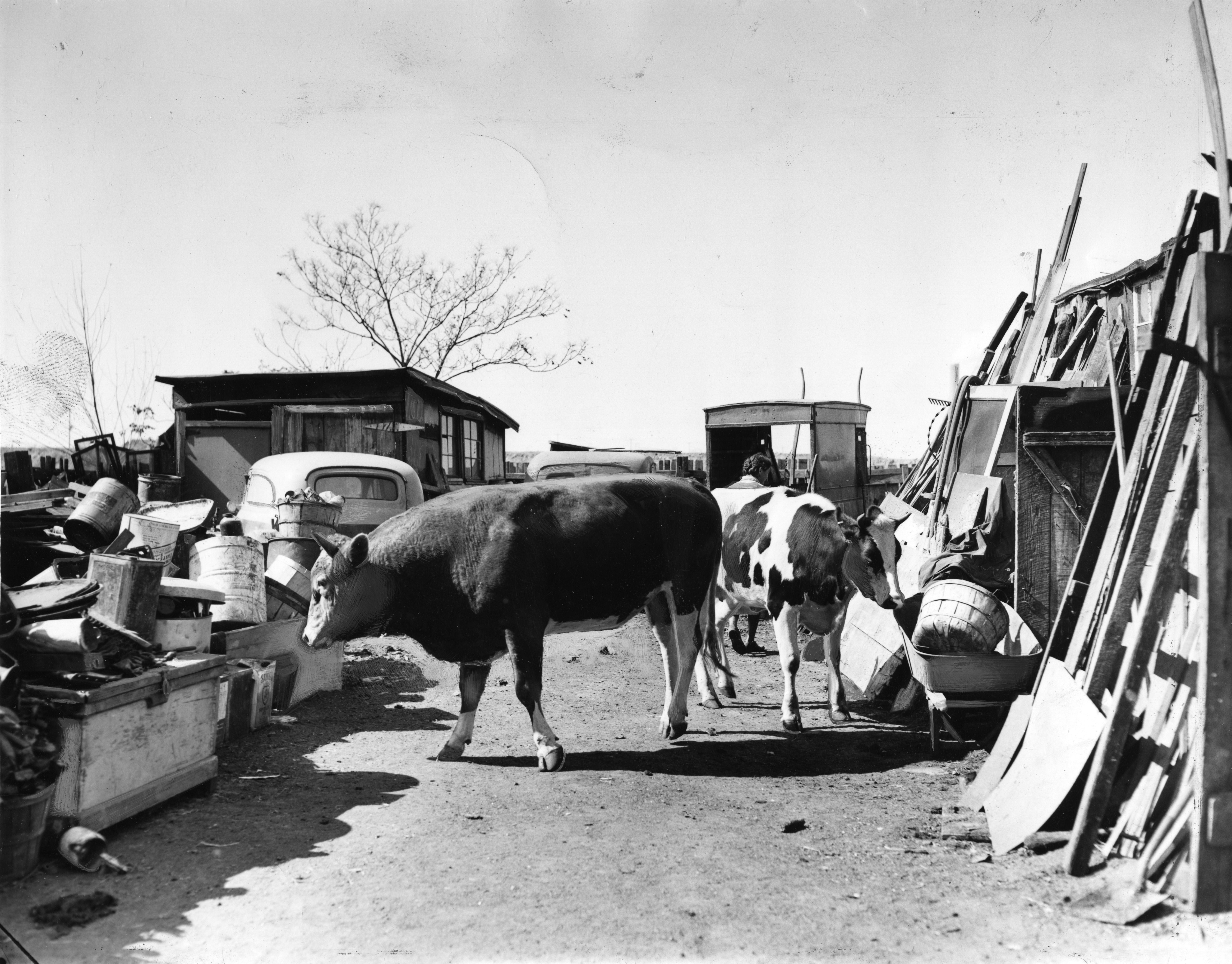

But the city fought its way southward through the marshes and farms that used to occupy that land. By the 20th century, the battle was largely over. The exception lay in deepest South Philly, below Oregon Avenue, where an incongruous community of farmers and squatters hung on until the 1950s.

Stonehouse Lane is one of the dozens of forgotten neighborhoods in this old city that have been bulldozed, burned, or otherwise brutalized. One origin story alleges that this particular corner of Philadelphia was formed by Hessian mercenaries who weren’t quite sure what to do when General Cornwallis surrendered.

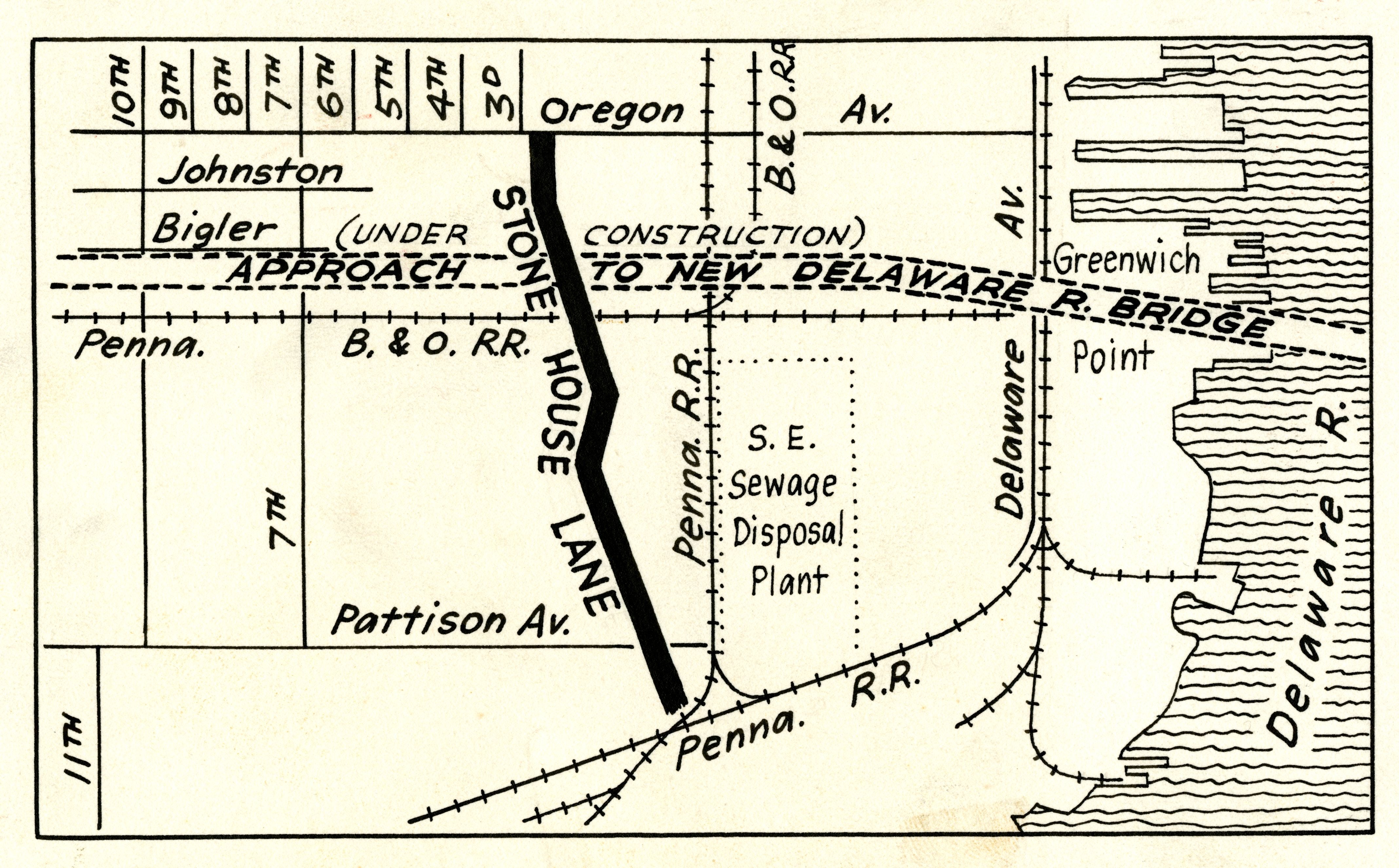

Despite Stonehouse Lane’s murky origins, by the 20th century it seemed a clear anachronism in a modernizing, industrial city. The road that formed the spine of the community wound its way down from Oregon Avenue past Pattison Avenue to the Pennsylvania Railroad tracks. It was flanked on both sides by canals. Each house featured a bridge that would allow residents to cross from the street to their front doors. There was no running water and the sewer system didn’t stretch down that far south either. The closest trolleys were a mile to the north on Oregon Avenue, and burning piles of trash on its northern border hemmed in the community. This, just six miles from City Hall.

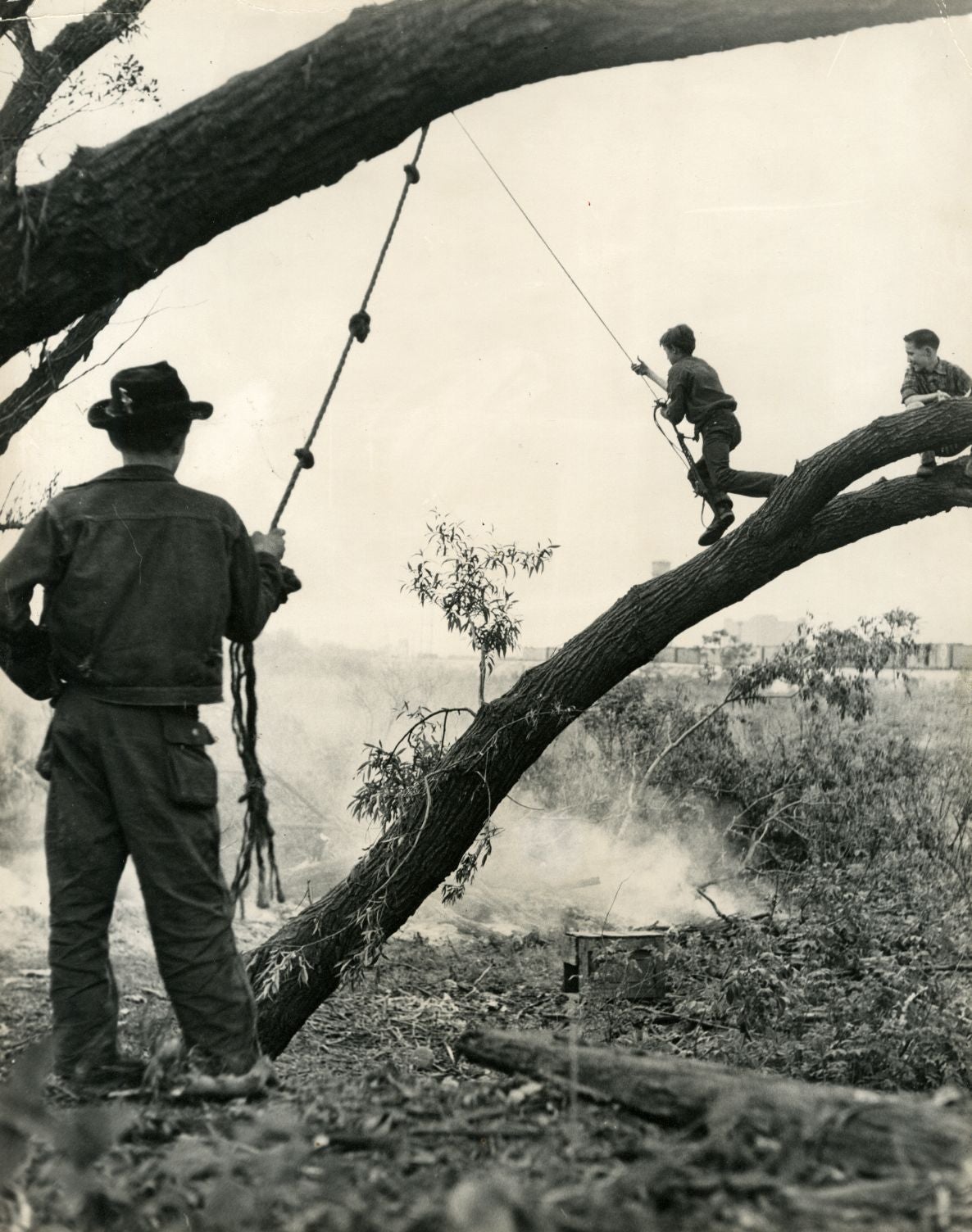

Nonetheless, the denizens of Stonehouse Lane kept animals in great abundance until the neighborhood’s destruction. Their micro-herds included cattle, pigs, goats, ducks, horses, and what one reporter described as “an unbelievable number of mongrel dogs romp[ing] among the tin cans that are scattered everywhere.”

The Philadelphia Evening Bulletin periodically sent journalists to Stonehouse Lane for either slice of life stories or to cover the latest eviction attempt.

Stonehouse Lane is “the Venice of Philadelphia, and has the distinction of being the only part of the city that has waterways instead of sidewalk,” enthused one reporter, in the typically florid prose of the 1920s and 1930s. “It is reminiscent of the older days when castles were built with drawbridges, but the knights of long ago never cared more for their pretentious abodes than the inhabitants of these odd little houses care for theirs.”

As the edge of the city, the water running past the residents’ doorsteps wasn’t drinkable. There wasn’t much potable water at all, as the wells contained dangerous levels of rust. Instead the residents got it from a fire hydrant on Pattison Avenue.

The other staples of municipal infrastructure weren’t up to snuff either. As late as the 1920s, electricity wasn’t commonplace in Stonehouse Lane yet. All the houses were all lit with kerosene lamps, while the neighborhood’s general store was surrounded by highly flammable barrels of the fuel.

The residents did not own the land but they dutifully voted for the Republican machine—their division was famous because no Democratic vote was ever tallied there until the later 1930s—which no doubt helped them fight off repeated eviction attempts.

One of the attempted dispossession campaigns resulted from a misbegotten attempt to replace the community with a private airport. Many of the residents on Stonehouse Lane owned their homes, but they didn’t own the land underneath it (trailer parks today are operated in much the same way). But with protest and political support the campaign was defeated. A later attempt resulted in the constables who attempted to enforce the evictions being beaten. The police declined to enforce the evictions themselves, perhaps.

After World War Two, Stonehouse Lane made its last stand. The community had stopped paying even nominal ground rents in the late 1930s. They were still stealing water from the city and they also weren’t paying taxes. But the neighborhood kept on receiving public services. The houses didn’t bear any addresses, but the mail was delivered to 3500 Stonehouse Lane and the postman knew all the families well enough that the 200 households each got what was coming to them. The school bus picked up those who went to public school, while those in Catholic school walked to Our Lady of Mount Carmel in what is now the Whitman neighborhood.

Despite their antiquated circumstances, the residents also took part in the postwar boom. Those interviewed by the Bulletin included truckers, factory workers, mechanics, train engineers, and longshoremen. These same families struggled through the Depression years, but by the mid-1950s most on Stonehouse Lane enjoyed telephones, television sets and automobiles (including one family with a Cadillac, the bulletin noted). However, many of these appliances were supported by pirated electricity.

The helter-skelter infrastructure resulted in headaches for any who tried to intervene. A favorite hazing ritual of the Department o Licenses & Inspections was to send rookies down to Stonehouse Lane, where they would spend days writing up all the violations. Then their supervisors would laugh it off, and throw the stacks of paper away.

The Walt Whitman Bridge finally did in Stonehouse Lane because the approaches along Pattison Avenue cut right through the neighborhood. “We always drove away those pests who tried to dispossess us,” a longshoreman told a Bulletin reporter in 1955, “but what can you do against a bulldozer?”

Although there had been calls for the squatter-farmers eviction for the previous fifty years, this time they couldn’t muster the political wherewithal to fight back. By 1955 only 274 people remained, less than half the former population. A 1955 census by the city found 97 occupied houses with 809 violations of the housing code among them. About half had no indoor toilets or proper plumbing, and almost as many relied on dangerous kerosene stoves for heat. Indeed, the neighborhood’s demise was also sped by the deaths of four children in 1954, who were consumed in a fire caused by a jerry-rigged electrical system.

By the end of 1956 everyone had moved out, or been moved out. The city burned all of the homes. Today Stonehouse Lane is completely paved over. The Oregon diner sits on the northern stretch of where the neighborhood stood. The built environment still bends slightly to its old contours as the blog The Necessity for Ruins once pointed out. But no other trace remains of the last rural community that survived the forward march of urban South Philadelphia.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.