Did you know New Jersey had a Levittown?

William Levitt built his third Levittown in New Jersey. He set it on the banks of Rancocas Creek in Burlington County.

-

A deposit bag from the Bank of Levittown is one of the surviving artifacts from the years when Willingboro was called Levittown. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

An aerial photograph from the 1960s shows the completed Levittown. (Willingboro Public Library Local History Collection)

-

Sen. John F. Kennedy, democratic presidential nominee, reaches out for unidentified youngster held out be enthusiastic father as the senatorís motorcade moved through out cheering crowd at Levittown, NJ., Oct. 16, 1960 this afternoon. Kennedy address throng officially estimated at 20,000 in Levittown, shopping plaza. The crowd interrupted Kennedyís speech with applause when he said he had disagreements with Vice President Nixon. (AP Photo)

-

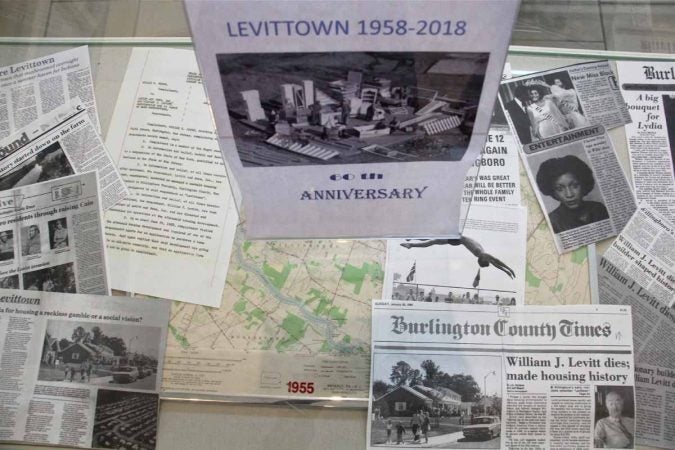

A display at the Willingboro Public Library looks to thje 60th anniversary of New Jersey's Levittown. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

Badges worn by the Levittown Emergency Squad are on display at the Willingboro Public Library. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

Willingboro, New Jersey, was developed as a Levittown in the 1950s. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

Levitt Parkway, a four lane road that winds through the middle of the New Jersey town of Willingboro, recalls the town's history as a Levittown. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

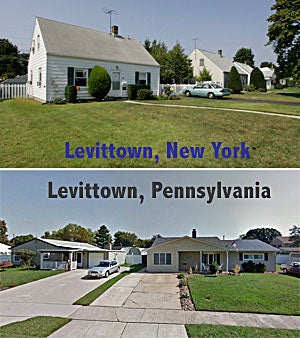

People don't think of Levittown, Pa. and Willingboro, N.J. as similar towns but they have a lot in common.

-

Residents got rid of the Levittown name because the three Levittowns shared some of the same street names. Shown here is a Willingboro Post Office. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

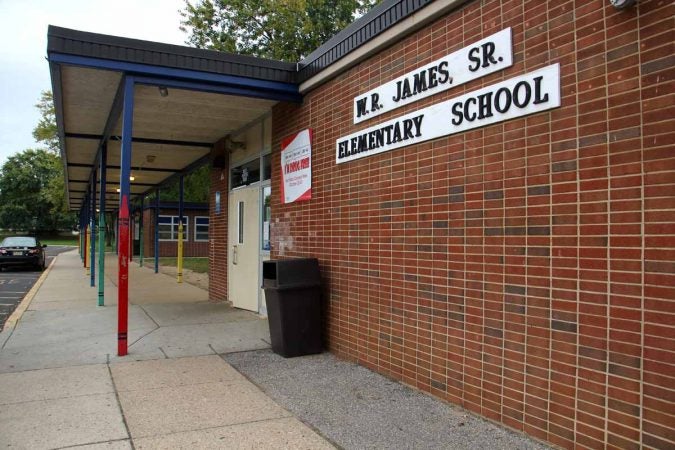

The Pennypacker Park Elementary School was renamed in 2001 for the Rev. W. R. James, whose discrimination lawsuit against Levitt and Sons opened the door to African American homeowners in Willingboro. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

Willingboro Township Municipal Complex. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

Willingboro's Mill Creek Park hosts a high school cross country meet. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

William Levitt is considered the father of the modern American suburb. His first Levittown was built on Long Island. He followed up with another planned community and created Levittown, Pennsylvania.

Less well known is Levittown, New Jersey. It was his third planned community and he set it on the banks of Rancocas Creek in Burlington County. Residents officially adopted the name Levittown, briefly, (1959-1963) but had second thoughts and reverted back to its historic name Willingboro, N.J.

According to Christine Hill, the director of the Willingboro Library, the driving motivation for dumping the Levittown name was over missing mail. Levitt had reused many street names he used in New York, Pennsylvania for his Levittown, N.J. This meant a lot of confused mail delivery in the days before ZIP codes.

She said she spoke to many residents while planning a 50th anniversary event a few years ago, and she said many who were residents at the time still seem keenly annoyed about the confusion of having three Levittowns with many of the same street names.

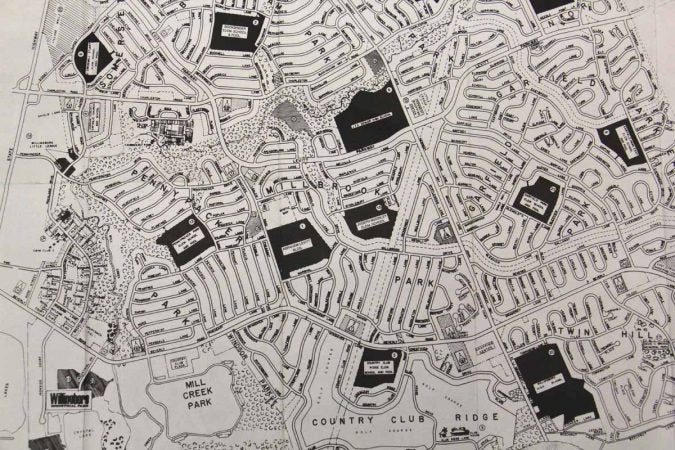

But the name change didn’t alter the character of the township. “It’s still a Levittown,” she said. Signs of Levittown can still be seen. The Levitt Parkway, with four lanes and a grassy median, runs through town, and the layout of neighborhood streets come from Levitt.

New American lifestyle

Family life was at the center of Levitt’s plans. He planned the communities so that every kid would be able to walk to school. “The basic planning unit for Levittown was the master block, a roughly mile-square area that encompassed three to five variously sized neighborhoods, also known as ‘sections.’ Each section contained on average between 300 and 500 houses,” reads part of an explanation on the State Museum of Pennsylvania’s website. The plans also included shopping areas, recreation facilities and other amenities aimed at creating a small-town feel, even though thousands of houses were going up at once.

Not for everyone

“The kid’s perspective was that it was a very boring place,” said Bob Barnett. He was 5 when his parents moved to Levittown, N.J. Growing up at the height of the Baby Boom, Barnett saw his town change, from a child’s perspective. Levitt was one of the first builders to put a television in every home sold. But for Barnett, the TV was not a big part of childhood. “My parents would shoo me out the door,” he said. The neighborhood kids would play together, including chasing the mosquito truck that sprayed the neighborhood. “We were running behind the spray truck, getting into the fog,” he said. “I’m not sure what they were using, but I’m sure it wasn’t good for us.”

Which house is yours?

To many who abhor the suburbs, it’s often said that the houses, despite the different models, look all the same. Barnett says there’s even a famous suburban legend, of someone getting lost among the miles of identical houses, unable to find his home. There’s no reason to believe that ever really happened, Barnett says Levitt included a way of finding your way through the community. Each street name began with the same letter as the section name. Barnett grew up on Genesee Lane, in Garfield Park.

Priced to sell

Levittowns were popular because they offered new affordable single-family homes. They were built fast, and built cheap with prices ranging from $12,000 for the Jublilee model to $17,500 for the Country Clubber. Levitt’s homes were attractive to WWII veterans who under the GI Bill were eligible for low interest loans.

This put the suburban dream in reach for many but not for everyone. While Willingboro today is 75 percent African-American, that’s not the way Levitt had imagined it.

Whites only

Legal segregation remained in force throughout the South in the 1950s, but the North, the process was most subtle, if just as noxious. Levitt and Sons would not sell to blacks, and included with each house was a deed covenant restricting sales to “the Caucasian race.”

“Bill Levitt would probably have considered himself a social progressive,” said Curt Miner, a senior history curator for the State Museum of Pennsylvania, who put together an exhibit on the Levittown experience. But Levitt did not believe whites would continue to buy his houses if his developments were integrated.

“As a Jew, I have no room in my mind or heart for racial prejudice. But I have come to know that if we sell one house to a Negro family, then 90 or 95 percent of our white customers will not buy into the community. This is their attitude, not ours. As a company, our position is simply this: We can solve a housing problem, or we can try to solve a racial problem, but we cannot combine the two,” said Levitt, as quoted in a New York Times review of Richard Rothstein’s book “The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America.”

Christine Hill said the integration of Willingboro began with a lawsuit brought by Rev. Willie James, which overturned the legality of race restrictive covenants in New Jersey. Charles and Vera Williams.became the first black family to own a home in Levittown, N.J.

She said the New Jersey community learned hard lessons from the experience of Levittown, Pa. There, when William and Daisy Meyers bought a home in the Dogwood Hallow section in 1957, harassment and mob violence led to an intervention by state police. The Meyers stayed, despite the intimidation. “Levittown, N.J., had a happier ending,” Hill said. A group of clergy members worked to allow a smoother transition.

Today, she said, the township is doing well. It was hard hit in the 2008 recession, she said, but it’s bouncing back, and now has a growing community of immigrants from African countries, particularly from Liberia.

Hill plans to celebrate the 60th anniversary of the start of Levittown, N.J., next year, with an event at the Willingboro Library on Saturday, Oct. 13, 2018. She invites anyone who lived in the town before 1970 to come and share their experience

Other Levittowns

Alfred Levitt launched the construction business during the Great Depression, but it was his son, William Levitt, who built it into an empire. Sometimes called the Henry Ford of housing, William Levitt brought mass production techniques to construction, building more than 17,000 homes between 1951 and 1957.

In addition to the three major projects in New York, Pennsylvania and New Jersey, the company built developments in Puerto Rico, near Paris, France, and throughout the country. Levitt built developments in 16 states, as well as in Canada.

In 1964, ITT bought Levitt and Sons, for a reported $90 million. Levitt had plenty of critics while he was still building. Initially lauded as the man who created the suburbs, that became more of a criticism as time went on. Some suggested the buildings were cheaply made and all looked alike. Songs and novels parodied suburban life, even as millions moved out of the cities, a migration Miner said was larger than the fabled move west generations earlier.

As Miner sees it, the people leaving miserable accommodations in urban rowhouses or from rural communities welcomed the clean, modern homes.

“They didn’t see this as uniform or drab,” he said.

What’s more, owners almost immediately began modifying the houses, which were designed for expansion. “They’re not cookie cutter houses anymore,” he said.

The fact that the homes remain indicates that they were not so poorly built, Miner said. While the developments in Pennsylvania and New Jersey were once extraordinary, he said, they now don’t look all that much different from the surrounding communities, an indication of how Levitt’s vision has become the American norm.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.