Kenyatta Johnson corruption case heads to trial after pandemic delays

Prosecutors say the Democrat received thousands of dollars for helping a nonprofit developer hang onto valuable real estate in his legislative district.

Philadelphia City Councilmember Kenyatta Johnson. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Philadelphia City Councilmember Kenyatta Johnson and his wife, political consultant Dawn Chavous, are headed to court on Monday, more than two years after they were charged in a federal fraud and racketeering case.

The couple will be joined by Abdur Rahim Islam and Shahied Dawan, two former executives at Universal Companies, a prominent nonprofit real estate developer and charter-school operator headquartered in Johnson’s legislative district.

Federal prosecutors say the co-defendants participated in a tangled quid pro quo that saw Johnson use his council seat to help Universal in exchange for a series of bribes concealed as payments to Chavous’ consulting firm, which the nonprofit had hired.

Johnson and Chavous each face up to 40 years in prison. Both have maintained their innocence, with Johnson calling himself a “victim of overzealous federal prosecutors.”

“My client acted in the exact same way he would have acted irrespective of any contracts that Dawn Chavous had. Didn’t take them into consideration one way or the other. Did what he thought was appropriate under the circumstances and was best for his community and stands behind his actions,” said Patrick Egan, Johnson’s defense attorney.

The case is slated to take at least three weeks, and could result in City Council losing a second sitting lawmaker to public corruption this year, a level of ignominy not seen since the Abscam scandal in the early 1980s when three members faced federal indictments. In January, Councilmember Bobby Henon resigned after he was convicted of bribery and conspiracy alongside powerful labor leader John “Johnny Doc” Dougherty.

Quid pro quo or councilmanic prerogative?

Johnson’s fate is tied to valuable real estate Universal owned in South Philadelphia. One property was allegedly sold to help Universal pay off a debt connected to a separate scheme to expand its charter school operation beyond Philadelphia.

Prosecutors say the nonprofit paid Chavous nearly $67,000 in consulting work so her husband would help it maintain control of the former Royal Theater on South Street, as well as a set of parcels on Bainbridge Street, which Universal got cheap from the city under an agreement to develop single-family homes on the land.

Chavous allegedly transferred the money to a personal account she and Johnson used to make mortgage, loan, and credit card payments, according to the indictment, which also contends that Chavous did “very little work” in exchange for the payments from Universal.

Chavous denies that claim, describing the challenge to her “work, ethics, and integrity” as “devastating.”

“I’m confident when this is over, the fact will reveal that I have done nothing wrong and my name and my family’s name will be cleared so we can put this behind us,” said Chavous in a written statement released in response to the indictment.

Prosecutors assigned to the case declined to comment.

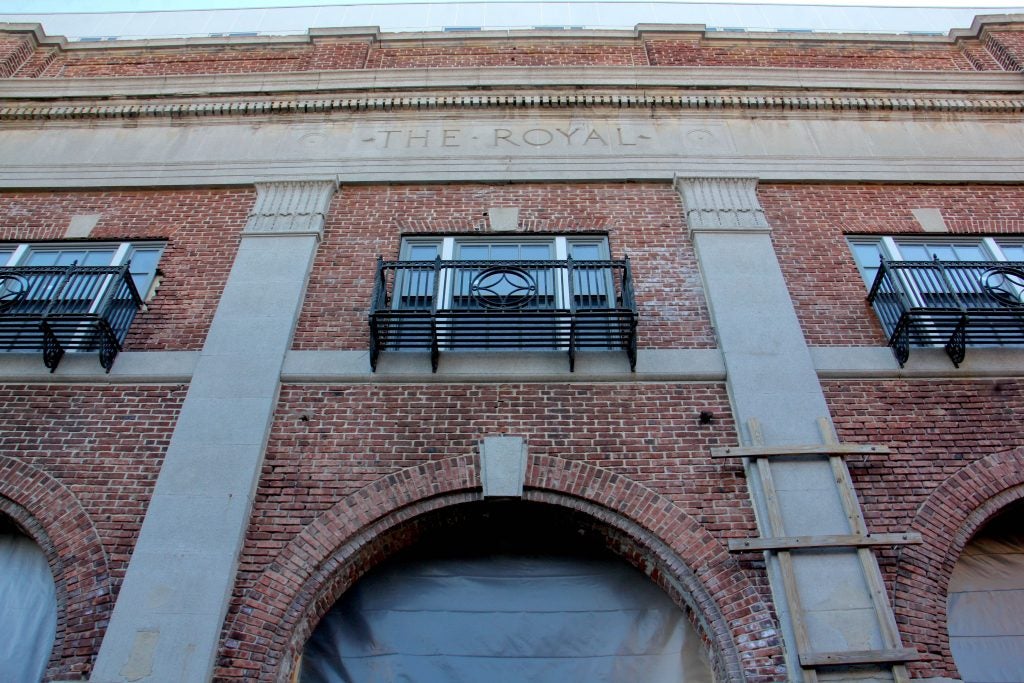

In 2000, while Islam was CEO of Universal, the organization acquired the Royal Theater from the Preservation Alliance for Greater Philadelphia. The nonprofit planned to stabilize and develop the historic property as an anchor for a cultural district.

But by 2008, the building remained undeveloped, leading Universal to explore alternatives.

None of them panned out, including an attempt to sell the building.

By spring of 2013, Universal was filing an application with the Philadelphia Historical Commission so it could demolish the crumbling theater and build something from scratch. In its application, the nonprofit explained that the building had become a “financial hardship” because of the way it was zoned, according to the indictment.

That May, a neighbor filed a conservatorship petition with the hope of having a judge award the blighted theater to another developer.

Universal hired Chavous the same month.

In 2014, while Johnson’s wife was still under contract with the nonprofit, the Democrat introduced zoning legislation to alter the parking requirements and height maximums for the theater. The move, which essentially extinguished the conservatorship effort, came days after Chavous deposited a $17,000 check from Universal, according to court documents.

The nonprofit later sold the decrepit theater, netting $2.7 million after paying closing costs, real estate taxes, and other expenses.

The theater has since been converted into apartments and a restaurant fronting South Street.

A ‘hijacked’ nonprofit

The same year Johnson introduced the zoning bill, he effectively stopped the city from reclaiming vacant land Universal owned on the 1300 block of Bainbridge Street. This occurred after Universal violated its 2005 agreement with the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority, which required the nonprofit to build 109 single-family homes on the land.

According to the indictment, Johnson told PRA officials he didn’t support the city’s efforts to take back the land shortly after his wife alerted Universal about them. Prosecutors say Johnson’s decision had a “chilling effect” on the process, in part because of councilmanic prerogative. The long-standing practice effectively gives council members the final say over development in their districts.

David Laigaie, Islam’s attorney, declined to comment.

The corruption case will also focus on crimes allegedly committed by the former CEO and Dawan, the nonprofit’s CFO, in service of Universal’s charter school expansion, as well as their personal bank accounts.

“In essence, this indictment charges that Universal Companies was hijacked by Islam and Dawan and turned into a criminal enterprise,” said U.S. District Attorney Jennifer Arbittier Williams in January 2020.

Starting in December 2014, prosecutors say the pair bribed Michael Bonds while he was serving as president of the Milwaukee Board of School Directors. Bonds, who was convicted in 2019, pleaded guilty to accepting $18,000 from Universal in exchange for his help making the nonprofit’s expansion into the city a reality.

Bonds’ actions included motioning the school board to approve more favorable lease terms for the charter schools they opened there, even as the nonprofit was struggling to fund the expansion. Islam and Dawan allegedly disguised the bribes as payments to a bookstore Bonds owned.

The government also accuses the pair of enriching themselves with Universal’s money, as the company was “hemorrhaging” cash. According to the indictment, the men stole more than $300,000 from the nonprofit, with Islam and Dawan often listing the unauthorized withdrawals as “bonuses.”

Islam also submitted his personal car insurance for reimbursement, as well as political contributions, personal vacations, and gym memberships.

As CEO of Universal, Islam earned $170,000 a year. Dawan’s salary was $160,000.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.