Justice is not blind when celebrity outweighs criminal behavior

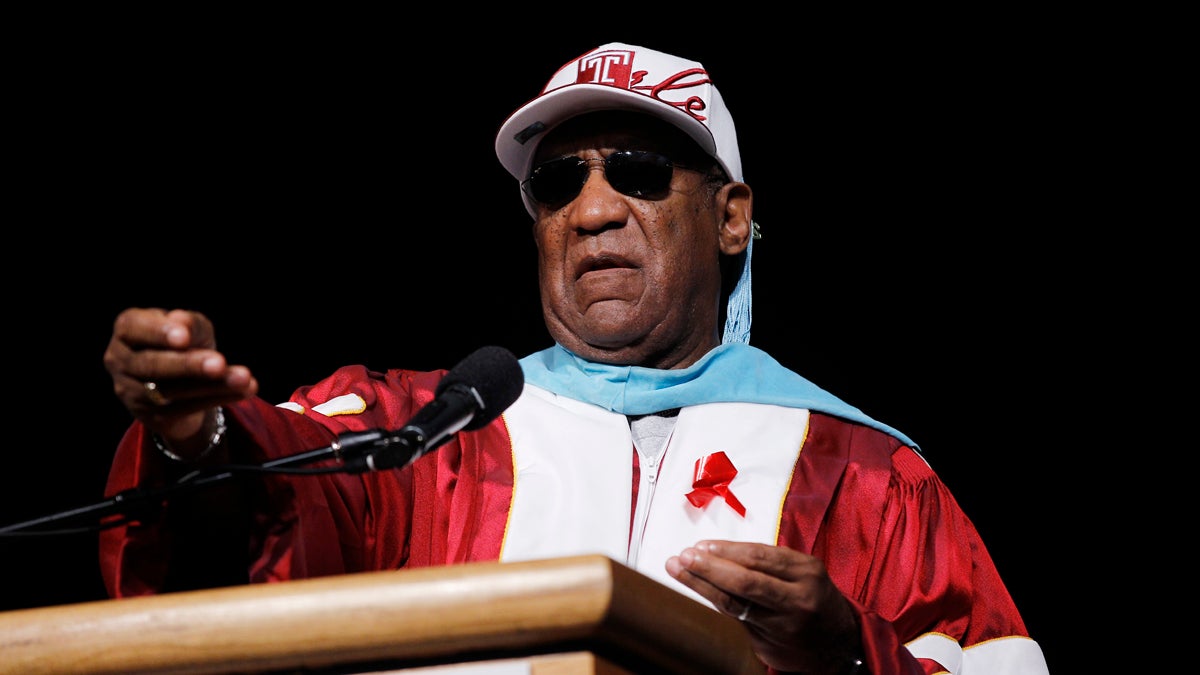

Bill Cosby is shown at Temple University 2011 commencement in Philadelphia. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)

Twelve years ago this month, I attended my freshman orientation at Temple University. One of the highlights was Cosby 101, an unofficial “class” by Bill Cosby. “Our family loves Dr. Cosby!” I gushed. It’s hard not to cringe when I tell that story to friends now.

Twelve years ago this month, I attended my freshman orientation at Temple University. One of the highlights was Cosby 101, an unofficial “class” by Bill Cosby, where he offered a “go make Temple proud” pep talk and stuck around to chat with new students afterwards. I met the Coz, told him how much I looked up to him and wanted to be a role model for Temple like he was, and even gave an interview to KYW Newsradio about the event.

“Our family loves Dr. Cosby!” I gushed.

It’s hard not to cringe when I tell that story to friends now. The public didn’t know the full extent of Cosby’s criminal behavior back then, but it’s hard to take ourselves off the hook (myself included) when we had a chance to call him out on it back in 2005, when news of a lawsuit against him alleging sexual assault first broke.

Cosby isn’t the first entertainer whose behavior elicits such widespread feelings of disgust, but when we consider past criminal acts by celebrities who do not receive the same level of scrutiny, it raises troubling questions about fame, history, and what criteria determine if an entertainer is worthy of our forgiveness.

Whether you want to admit it or not, the growing frenzy surrounding Cosby’s case has a lot to do with our perceptions of race and our values when it comes to the law.

It’s all about image

Before he made headlines as a sexual predator, Cosby was America’s favorite television dad on “The Cosby Show.” Before that he was a champion of educational television with “The Electric Company” and breaking barriers as one of the few black actors on network television with the show “I Spy.” His wholesome image was the perfect shield against bad publicity or accusations of misconduct.

On the flip side, an artist whose persona is tough and rebellious barely registers on the public’s outrage scale when run-ins with the law occur. Before he was an actor, Mark Wahlberg was known as bad-boy rapper Marky Mark. He was also known to Boston police for multiple arrests involving drug dealing and harassment. In 1988, 16-year-old Wahlberg was arrested for attempted murder after he attacked two Vietnamese men with a five-foot-long stick. He served 45 days of a two-year sentence, a punishment which he says inspired him to turn his life around.

The actor’s last brush with the law occurred during his music career in 1992, when he and a friend viciously beat up his neighbor in what witnesses say was an unprovoked attack. The incident was eventually resolved by an out-of-court settlement.

Despite his violent youth, Mark Wahlberg was able to move past his tough guy image and become a versatile actor and businessman. When magazines profile him, his violent past is downgraded from that of a drug-dealing racist with a chip on his shoulder to a misguided kid with potential who rose above his surroundings to become a respected American actor.

Forgiving, and forgetting history

An artist’s image may not always help erase bad behavior, but timing and contributions to pop culture can provide extenuating circumstances. Actor Tim Allen, who has portrayed a happy, wholesome family man on not one but two ABC sitcoms, was arrested for drug trafficking as a young man in the late 1970s. Had it not been for a compassionate judge (and Allen’s cooperation in identifying other drug dealers for the prosecution), the comedian-turned-actor would still be behind bars.

By the time he achieved fame as Tim “The Tool Man” Taylor on the hit show “Home Improvement” in the 1990s, Allen’s turn as convicted felon was largely ignored or downplayed as life experience. After all, in the court of public opinion, what happens in an artist’s life before they become famous doesn’t count.

Before Allen’s jail time or Cosby’s civil suit, it was film director Roman Polanski who set the standard. In 1978, the celebrated director of “Rosemary’s Baby” and “Chinatown” was arrested for drugging and raping a 13-year-old girl in Los Angeles. Polanski eventually pled guilty to unlawful sexual intercourse with a minor, and fled to London hours before his sentencing to avoid jail time.

The fallout should have ended Polanski’s career permanently. For many years, it appeared that it had, until 2002, when his film “The Pianist” took top prizes at countless awards ceremonies. Since that time, Polanski has regained his status as a renowned filmmaker, and in 2009, the woman at the center of his rape case petitioned the Los Angeles County district attorney to dismiss the charges against him.

It would seem that enough time had passed between Polanski’s case and the release of his Academy Award-winning film for the public to forget his crime. His own history may have contributed to that – “The Pianist” was the story of a gifted Jewish concert pianist trying to survive the Holocaust in war-torn Warsaw. Polanski himself was a survivor of the Holocaust, a fact that was referred to often in publicity about the film.

In articles written about Polanski’s life during the last 13 years, his 1977 crime is referred to as “statutory rape” or “an unlawful sexual relationship.” These word choices imply that the victim consented to sex with Polanski and just happened to be underage at the time. Today’s readers who didn’t live through the news coverage of his case are left in the dark about crimes he committed that night that he eventually wasn’t charged with, charges too graphic to print here.

A different line of questioning

It’s impossible to imagine the public forgiving Cosby for his transgressions at this stage. He doesn’t have a story of remorse and rehabilitation Wahlberg. He didn’t commit his crimes before he became a household name like Allen.

Would we be able to downplay Wahlberg’s violent past if he had brutally beaten two Vietnamese girls instead of two Vietnamese men?

Would there be forgiveness for Polanski if he were a black rapper?

If court papers proved that Cosby had been guilty of embezzling money instead of committing acts of rape, would we still create hashtags about it on Twitter?

The growing number of women coming forward no doubt contributed to the erosion of Cosby’s image and reputation, but the thing that bothers me most is that when one of these victims took her attacker to court in 2005, the story fizzled out. America’s Favorite Dad emerged from the situation relatively unscathed. It took a male comedian calling Cosby a rapist 10 years later and more than 40 women sharing horrifically similar stories of abuse to get us to agree that he had crossed the line.

We live in a time where the murder of a lion in Africa merits greater outrage than the suspicious death of an African-American woman in police custody. We desire a court of law that gets justice for all victims, yet we allow ourselves to forget the heinous crimes a person commits because we deem some sins (and skin colors) more offensive than others.

At the end of the day, Cecil the lion and Sandra Bland are still dead. Wahlberg, Allen, Polanski are still honing their craft. Cosby will never mount the comeback he hoped for. Over 40 women (that we know of) still face a long road to recovery and acknowledgement.

And Cosby 101 is postponed indefinitely.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.