‘It’s not a trick:’ Drug users turning to some N.J. police departments for help

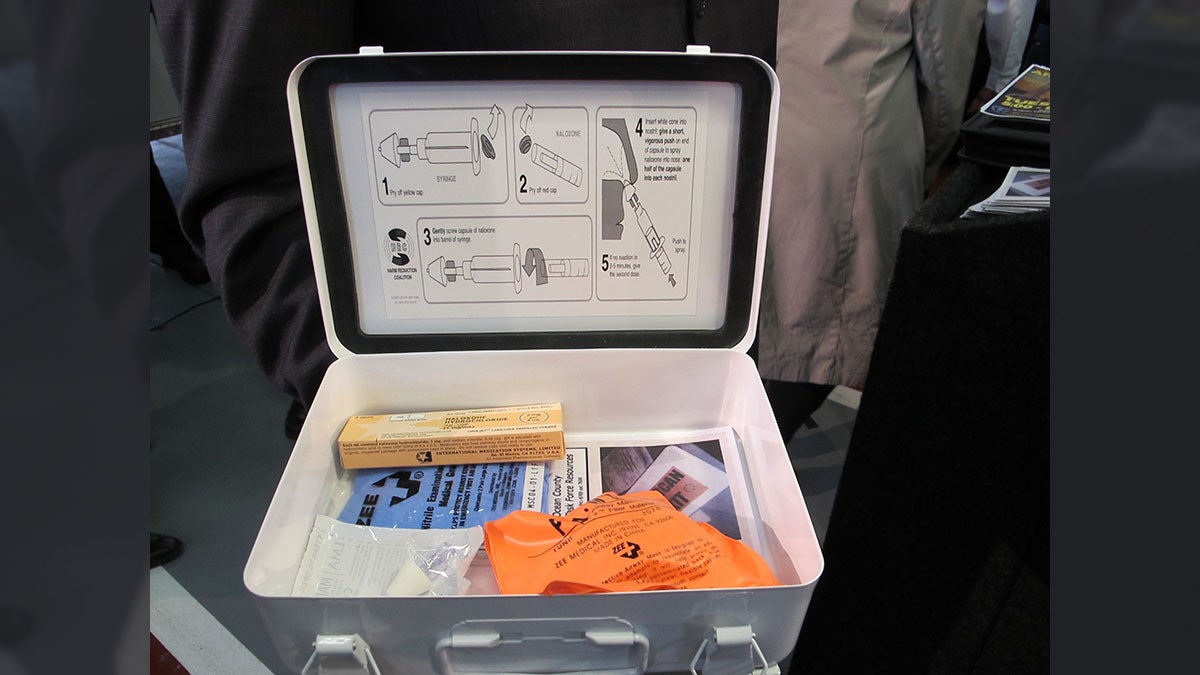

Narcan emergency kit (Phil Gregory / WHYY)

Drug users desperate to kick the habit are now turning to some New Jersey police departments offering help instead of arrest.

About 150 people have showed up at police stations in Brick and Manchester Townships in Ocean County since the Heroin Addiction Response Program or HARP launched in January, according to Brick Township police chief James Riccio.

“These people have reached that bottom I guess and want the help,” Riccio said. “The first few came in. I guess they tested the waters to see that we were actually telling them the truth. We weren’t trying to set them up.

“I guess the word is getting out that we’ll actually get them the help they’re looking for. It’s not a trick.”

When they walk in, instead of facing arrest, the chief said there’s a brief assessment.

“We’ll ask them questions about the type of drug and the type of addiction that they’ve had, when they’ve last used,” Riccio said. “It will help the assessors better determine what type of treatment they need.”

After that process, participants are transported to treatment facilities where clinicians evaluates whether they should receive inpatient or outpatient treatment or detox. Participants are not required to have health insurance and the program is paid for using drug forfeiture money.

The perception police just want to prosecute drug users instead of helping them started to change with the advent of the opioid antidote nalaxone or Narcan, said Ocean County Prosecutor Joseph Coronato. Ocean County was among the first in New Jersey to begin equipping first responders with the antidote as part of a pilot program that began in 2014. Last year, 209 people died of overdoses in the county, while 505 overdoses were reversed using nalaxone, according to N.J. 101.5 radio.

“I think the image of the police officer just arresting our way out of the problem wasn’t successful for the last 40 years,” Coronato said. “But just because you administer Narcan doesn’t make you’re going to break the cycle of addition.”

So far, about 80 percent of the users seeking help at police stations are sticking with recovery programs, Coronato said. He credits that success to the recovery coaches who follow patients throughout the process.

“If they all of a sudden have… a problem along the way, there’s someone else, like a lifeline, that they can reach out to that they can talk to who they can relate to that gets them back on track,” he said.

Getting people into treatment benefits the community as well, said Brick Township Mayor John Ducey.

“The users a lot of the times, they’re the ones who are doing some of the petty crimes, opening car doors and stealing the change out of a car and things like that,” he said. “Now if they’re able to get help and get rehabilitation and become a productive member of society again, it adds to our battle against this unfortunate scourge of heroin.”

The program is expanding to Stafford Township. Similar efforts are underway at police departments in West Orange, Paramus, Mahwah, and Lyndhurst.

But Coronato cautions setting up these kinds of programs can be difficult.

“When somebody walks in, they walk into our police station carrying their valises, their suitcase. They’re prepared to do something, and as a result of that, you can’t say, ‘Come back tomorrow.’ You can’t say, ‘Wait six hours.’ You have to have the available detox beds so we can handle the volume as it comes in.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.